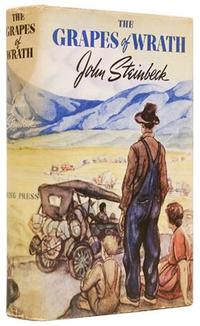

On April 14, 1939, The Viking Press published John Steinbeck’s most famous and enduring work, The Grapes of Wrath. This month, to commemorate the novel’s seventy-fifth anniversary, Penguin has just published On Reading The Grapes of Wrath by Susan Shillinglaw. A professor of English at San Jose State University and Scholar in Residence at the National Steinbeck Center, Shillinglaw has been director of the Steinbeck Research Center at San Jose State for eighteen years. Her previous publications include Carol and John Steinbeck: Portrait of a Marriage (U of Nevada Press, 2013).

In the following guest post, Professor Shillinglaw examines how Steinbeck’s investigative journalism laid the foundation for writing The Grapes of Wrath and how the novel still resonates today.

By Susan Shillinglaw

Seventy-five years after it was first published, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath remains as relevant—its cry for equity as sharp and insistent—as ever. The bruising honesty of the novel owes much to its journalistic roots. From August 1936 to February 1938, off and on for eighteen months, John Steinbeck conducted on-the-ground research, driving an old bakery truck from his Northern California home to the Central Valley, to Fresno and Button Willow and Bakersfield and Weedpatch. He bore witness to migrant woe, initially as an investigative reporter for the liberal San Francisco News.

In the summer of 1936, as Steinbeck was completing Of Mice and Men, the editor asked him to write a series of articles on migrant housing in California. A few months earlier, a federal government camp program had been launched to provide decent housing for migratory field workers. The plan was to build a dozen or more model migrant camps up and down the state. Two were open in 1936, one in Marysville near Sacramento and another in Arvin, near Bakersfield. Both enclaves faced strong opposition by local growers: if field workers came together in these government-run, safe and clean little communities, who knew what might happen. Strikes? Labor organizing? Protests?

Steinbeck’s assignment was to sway public opinion, soften hearts and minds steeled against the government camp program; illuminate the deplorable conditions in squatters’ camps; and break down “Okie” prejudice. “The migrants are hated for the following reasons,” he wrote in his first article of what became “The Harvest Gypsies” series: “that they are ignorant and dirty people, that they are carriers of disease, that they increase the necessity for police and the tax bill for schooling in a community, and that if they are allowed to organize they can, simply by refusing to work, wipe out the season’s crops. They are never received into a community nor into the life of a community. Wanderers in fact, they are never allowed to feel at home in the communities that demand their services.”

Change a few words and that might describe twenty-first-century resistance to illegal immigrants or the angry push-back on passage of the DREAM Act. Steinbeck’s assignment for the San Francisco News was to move readers to an empathetic recognition that those folks are our folks.

Some of Steinbeck’s research for “The Harvest Gypsies” series is embedded in The Grapes of Wrath in the Weedpatch camp chapters (22 and into 26), which describe an oasis of dignity for migrant families. Camp director Jim Rawley nudges the Joads to renewed self-respect, and his kindness was drawn closely on that of Tom Collins, the director of the Arvin camp that Steinbeck visited in the late summer of 1936. Steinbeck read Tom’s detailed camp reports, running some 30 pages per week and carefully recording the number of campers, their jobs, their sicknesses and songs and troubles. Steinbeck traveled with Tom and interviewed migrants with him. He and Tom brought food to the destitute and helped with the sick. “To Tom who lived it,” the dedication to The Grapes of Wrath reads, in part.

Rereading the novel in 2014 sparks countless moments of recognition all over again, context shifted, impact fresh. The Grapes of Wrath continues to speak so powerfully in our era because Steinbeck dug in so deeply and with such passionate conviction into his own.

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| The Grapes of Wrath and Other Writings 1936–1941 |

In some ways the book feels more timely than ever this year, as we in California emerge from a very discontented winter. As I write a green skin stretches over the state, pale shoots that belie what we know: that aquifers are depleted; that this winter’s rainfall was late and brief; that the parched Central Valley soil might not, as in past decades, produce 50% of the nation’s fruits and vegetables—or 99% of the country’s artichokes, dates, olives, walnuts and (water-thirsty) almonds. “The spring is beautiful in California,” Steinbeck writes in Chapter 25 of The Grapes of Wrath. “Valleys in which the fruit blossoms are fragrant pink and white waters in a shallow sea. . . . And on the level vegetable lands are the mile-long rows of pale green lettuce and the spindly little cauliflowers, the gray-green unearthly artichoke plants.”

All that is still visible in Monterey County, Steinbeck country, even in a drought year. Other California stories, however, aren’t pink or gray-green or lovely.

Steinbeck’s terrain was unlovely stories—of what happens when the green promise does not deliver or the fecund earth does not produce—be it in Oklahoma or in California. The soil dries and poor people get tractored off—or laid off, the threat this harvest season, when many fewer workers will be needed. Houses are repossessed and families move on, to more fragile homes. Or, as in Chapter 25, California growers burn surplus crops to keep prices high “and in the eyes of the hungry there is a growing wrath.”

John Steinbeck startles readers to attention, then and now. Another drought. Banks foreclosing—yet again. Angry workers demanding fair wages—$10.10 an hour as a living wage. Decent housing and safe working conditions for fieldworkers still making news, today’s stories about women who are sexually vulnerable in the fields. His saga of land use and workers’ anguish is as poignant, maybe more so, in this year of “exceptional” drought in much of California; in this decade where the voices of the “98%”—the wide swath of Americans that interested John Steinbeck throughout his career—are muted. Power versus powerlessness was his narrative arc. And it’s ours as well.

Communication between two humans even under the best of circumstances is staggeringly difficult. When I am able to get through to establish a contact I have a sense of joy. That is the real base of all the arts—they are kind of frantic signals like mirror flashes between mountains. . . .

—John Steinbeck