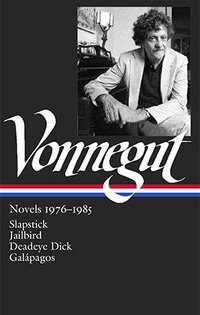

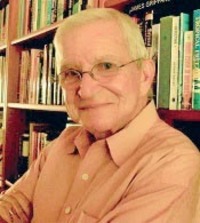

The Library of America has just published Kurt Vonnegut: Novels 1976–1985, the third volume of the definitive edition of Vonnegut’s fiction. We recently interviewed his longtime friend, the novelist and journalist Dan Wakefield (Going All the Way, Starting Over), who recently edited and wrote the introductions for If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?: Advice to the Young (a selection of Vonnegut’s speeches published by Seven Stories Press) and Kurt Vonnegut: Letters (Random House).

LOA: How did you come to be friends with Kurt Vonnegut?

Wakefield: I went to the same high school in Indianapolis as Kurt Vonnegut, ten years after he graduated. We both wrote for our high school paper, The Shortridge Daily Echo, and the year after I graduated in 1950, Vonnegut’s short stories began to be published in Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and other popular weekly magazines of the era. I read everything he wrote that I could get my hands on, and met him in 1963 at the home of a mutual friend when he was living on Cape Cod and I was on a Nieman Fellowship in Journalism at Harvard. He was friendly, open, and funny, and we had a great time—not talking about writing, but about high school. Our special bond was that we both confessed to being failures in high school sports!

Vonnegut reviewed my first novel, Going All The Way, for LIFE magazine, and his words were instrumental in making the book a best seller. I always think of him as “The Godfather” of my work.

LOA: During the period 1976–1985, what was Kurt like when he was writing Slapstick, Jailbird, Deadeye Dick, and Galápagos?

Wakefield: During that period I had lunch with Kurt whenever I went to New York, and it was always an entertaining occasion. Earlier, in the years of early struggle and rejections, when Kurt was living on The Cape and helping to raise his family of three children and three of his sister’s orphaned sons, he had had few occasions to meet and socialize with other writers. Now that he had the chance, he really enjoyed being involved in the PEN Club in New York and helping writers in other countries, being a part of The National Academy of Arts and Letters, and getting to know and socialize with his peers.

At lunch we talked about mutual writer friends, like Richard Yates, and our hometown of Indianapolis, and he often suggested after lunch we go back to his house and make phone calls to people we knew in common. He loved calling information in different cities and tracking down people he had known in the past, just for the fun he had in re-connecting. He also enjoyed showing his support to writer friends and former students, cheering them on. He was one of the most loyal friends I ever had.

LOA: What is your favorite of these later novels?

Wakefield: I have always especially loved Jailbird. There is a first-person, essay-like opening in which Kurt tells of meeting an Indianapolis man who became a well-known labor organizer and activist named Powers Hapgood. Hapgood had been arrested and jailed for picketing and leading strikes and the Judge asked him why a man from such a distinguished Indianapolis family would engage in such activities.

“Why?” said Hapgood. . . . “Because of the Sermon on the Mount, sir.”

Vonnegut cites The Sermon on the Mount throughout his work, and in his sermon “Palm Sunday,” given to St. Clement’s Episcopal Church in New York City in 1980, he said “I am enchanted by the Sermon on the Mount. Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have received so far. Perhaps we will get another idea that good by and by—and then we will have two good ideas.”

Mercy, in fact, is the basic theme of all Kurt Vonnegut’s work.

LOA: Why do you think Vonnegut’s work has always appealed to young people?

Wakefield: Kurt always had a fresh way of looking at things, a way to make great issues accessible, and to point out phoniness and pretentiousness wherever he saw it, no matter how sacred the cow. He was the “truth teller,” the person who points out the elephant in the room. He said the truth was shocking because we so rarely hear it. Even before Slaughterhouse-Five made him famous, I used to see college students in Boston carrying around dog-eared paperback copies of Cat’s Cradle, a satire about an invented religion whose fake dogma was expressed in rhyming couplets.

He has sometimes been dismissed as a hero to the counterculture but if anything he was a counter-counter-culture hero. He dismissed the pop guru to the stars, Maharishi Mahesh Yoga, in the article “Yes, We Have No Nirvanas.” When Zen meditation was all the rage, he said we have a system in the West that also slows the heart rate and clears the mind—it’s called “reading short stories.” He called reading short stories “Buddhist Catnaps.”

LOA: What was his favorite anecdote?

Wakefield: He was honorary president of the American Humanist Association (he came from a long line of German freethinkers) and he loved to tell how he “slipped” while giving a eulogy of Isaac Asimov, the science fiction writer who was former president of The Humanist Association. “I said I was sure that Isaac was up in heaven now. That was the funniest thing I could have said to an audience of Humanists. I rolled them in the aisles!”

He loved to tell that story—I heard it more than once!