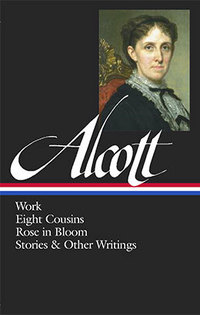

The latest Library of America volume, Louisa May Alcott: Work, Eight Cousins, Rose in Bloom, Stories & Other Writings, has just arrived from the printer and is available now exclusively from the LOA Web Store. (It will be released in bookstores at the end of August.)

We recently interviewed Susan Cheever, who edited the volume. Cheever is the author of thirteen books, including Louisa May Alcott: A Personal Biography and American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau.

LOA: This second Library of America volume of Alcott’s fiction collects three novels published in the 1870s, along with a number of short works. What is the relation of this collection to the Jo March trilogy?

Cheever: When I read Alcott’s Little Women as a girl, I thought I was Jo March—romantic, rebellious but lovable, ready to marry but only for true love. What did I know? Alcott was a writer who refused conventional ideas of women’s roles—ideas as tenacious today as they were in the 1860s. In fiction she settled Jo March with an unconventional conventional marriage. In real life Alcott said, “liberty is a better husband than love.”

The novel Work addresses women’s issues head on. The other novels and stories in this collection are inspired by different aspects of women’s lives in nineteenth-century America. In Eight Cousins and its sequel Rose in Bloom, Alcott uses Rose Campbell—an orphaned heiress with seven male cousins—to show the absurdity of the customs of dress and education which hampered her own young life. The stories “Anna’s Whim”—her “whim” is that men should talk to women the way they talk to other men—and “Kate’s Choice” also feature young women at social and emotional crossroads.

LOA: What personal discoveries did you make while at work on the volume?

Cheever: Alcott was sharply aware of what made money and what did not make money, and her careful accounting of her earnings is one of the most interesting aspects of her journal. The more I have learned about Alcott’s work and her life, the deeper and less girlish my connection to her has become. As a writer who makes a living from my work, I also keep careful accounts, worry about my ability to support myself and my family, and struggle to balance what my heart wants to write with what my financial situation requires me to write. Alcott had a difficult life as a writer in a family where she was often the only breadwinner. These later books reflect that reality with grit and honesty. They may be less popular because they are less sentimental, but because they are less sentimental, they all the more important.

LOA: Do you have a favorite piece in the collection?

Cheever: My favorite piece in the collection, and one of my favorite works of Alcott’s, is Work, a novel which directly addresses the principal question of Alcott’s life, a question we still ask today, how can we reconcile the needs of our professional and domestic lives? How can we find a way to support ourselves financially and still be good daughters and sisters?

Written over the ten most important years of Alcott’s life, Work was begun in 1861 as an autobiographical novel when she was still an unknown writer of potboilers from sleepy little Concord, Massachusetts. In 1868, urged by her editor, Thomas Niles, and her father, Bronson Alcott, she reluctantly took time out to write a book about girls. That book was the extraordinarily successful Little Women. As a result, by the time Work was finished in 1872, Alcott had gone from obscurity to fame as one of the best-loved and best-selling authors of the nineteenth century.

LOA: Any notable biographical anecdotes in connection with the works in this Library of America volume?

Cheever: One of the origins of Work was Alcott’s early essay “How I Went Out to Service” [also in this volume] in which she tells the horrid story of being hired out as a companion to the family of a man who seemed elegant and educated—James Richardson of Dedham—but who turned out to be brutish, unreasonable, and cheap. Trapped in the job for four weeks, the eighteen-year-old Alcott fumed and took notes. Richardson insultingly paid her a total of four dollars, but Alcott hoped the resulting essay would launch her career as a serious writer. She took it to the great editor James T. Fields of Ticknor & Fields in Boston. Fields, ensconced in his office above the Old Corner Bookstore, read the essay while Alcott waited, looked up at the author, and pronounced: “Stick to your teaching. You can’t write.” Alcott’s determination to prove him wrong was one of her many sources of inspiration.

LOA: How autobiographical is Work?

Cheever: Drawing on her essay about Rev. Richardson, as well as her own experience with jobs in nineteenth-century Boston—Alcott worked as a seamstress, a governess, a teacher and an actress—she wrote a powerful indictment of the way women are bullied by society—this was in the years when women were owned by their fathers and husbands and did not have the right to vote. The second half of the novel introduces a love affair with a man based on Alcott’s close friend Henry David Thoreau—his death scene is taken from Alcott’s own memoir Hospital Sketches, written after she served as a Civil War nurse in the Union Hospital in Washington, D.C. Alcott was in her forties when she published Work. The book’s advance enabled her to give her sister May money to study art in London and to help care for her aging mother—and she poured all of her hard won experience and insight into the story of Work’s heroine Christie Devon.

LOA: How closely connected was Louisa May Alcott with the early women’s movement?

Cheever: For Louisa May Alcott women’s issues were not a political cause but a personal necessity. She rejected the conventional nineteenth-century role of wife and mother and instead embraced the possibility of liberty and control over her own economic fate. As a result Alcott collided with society’s rules about the place of women in the world. Her first novels had to be published under an assumed name. Her first earnings were far less than her male contemporaries might have made. Alcott was an abolitionist and a temperance crusader, but her great political cause was the women’s equal rights amendment and women’s suffrage—“the cause of women is the cause of civilization,” she wrote. She supported Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony in their statement of the Rights of Women published on July 4th of 1876: “Yet, we cannot forget, even in this glad hour, that while all men of every race, and clime, and condition, have been invested with the full rights of citizenship, under our hospitable flag, all women still suffer the degradation of disfranchisement.” Alcott jubilantly concurred and wrote: “Three cheers for the girls of 1876!”