Last week The Library of America published Elmore Leonard: Four Crime Novels of the 1970s, which contains a quartet of crime novels set in Detroit: Fifty-Two Pickup, Swag, Unknown Man No. 89, and The Switch.

Lorenzo Carcaterra, the best-selling author of Sleepers and Gangster, whose most recent novel, The Wolf, was published earlier this summer by Random House, recalls what it was like learning the novelist’s trade from Leonard himself, whom he met thirty years ago.

The Master

Pete Hamill. George V. Higgins. Jack London. Alexandre Dumas. Harry Crews. Victor Hugo. Ernest Hemingway. Dashiell Hammett. John Irving. These are just a few of the writers whose works I have read, studied, and absorbed over the course of decades, as have thousands of others. They are the masters whose lessons never waver, who offer fresh insights with each new work and with every re-reading. At the very head of that distinguished group is Elmore “Dutch” Leonard, the dean of my writing university.

I was fortunate not only to have gone to school on Leonard’s work—learning as much as I could about pacing, using dialogue to not merely tell but describe, and realizing that not every hero need be painted with an unvarnished brush—but also to have spent time in his company.

I first met him on a People magazine assignment in 1984, flying to his home in Birmingham, Michigan, fresh off the success of his novel Stick. He was reed slender and soft spoken, never saying more than what needed to be said, his pristine office dominated by a large framed photo of Ernest Hemingway holding a fish nearly as tall as he was. “Got that in Key West,” Leonard said, catching me staring at the photo. “Didn’t pay much for it. Don’t think the fella who sold it to me knew that was Hemingway. Just another guy who caught another fish.”

He was in the early phase of the success that was to follow him for the rest of his writing life, but that didn’t seem to affect him much. He was a working writer before the media started glancing his way, before the accolades came pouring in, before books landed with yearly regularity on the bestseller lists. He had been working at his craft since selling his first short story in 1951, a western, and he didn’t stop until his death last August when he was just about halfway through yet another novel.

There were some bumps along the road but he kept at it, waking every morning at 5 and writing two pages of fiction before heading off to work at an advertising agency. Among those early works two stand out as classics: the short story “3:10 to Yuma” and the novel Hombre. Through those early years, he helped raise a family that would grow to five children, cave to the lure of drink and then come back to beat it, lose some jobs (he was dropped by one ad agency for copy he wrote about a pick-up truck—“It never breaks. You just get tired of looking at the S.O.B.”), wrote for movies and TV and kept at the novels. His turning point came when he signed with the legendary Hollywood talent agent, H. N. Swanson.

“I liked his westerns,” Swanson would tell me a few years after I met Leonard. “But no one was buying westerns anymore. I asked him two questions. Asked, ‘Do you like girls?’ He said yes to that. And then I asked if he could write a contemporary novel and get himself out of the west. He told me he could. I told him to get back to me when he did.”

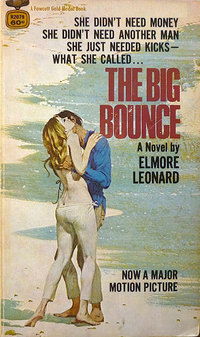

A year later, a Leonard novel called The Big Bounce landed on Swanson’s desk. He read it and then called Leonard. “I kept the conversation simple,” Swanson told me. “I told Leonard he was going to be a very rich man.”

Leonard worked the writing hard, making certain that each word chosen mattered, each sentence written essential. And every character fully sketched and brought close enough to life they could be touched. His heroes were lawmen and criminals and none were drawn in simple black and white. They were, to quote former New York State Supreme Court Justice and novelist Edwin Torres (Carlito’s Way), “people who lived after midnight and at that hour there is no black and white. At that hour every cat is grey.”

I stayed in touch with Leonard long after that profile ran in People, but I didn’t need to speak to him to keep learning about the writing life. All I needed to do was read his work—from the “Detroit novels” (four of which are included in the new Library of America collection) to his take on Hollywood with the brilliant Get Shorty down to Florida with LaBrava and into the world of music with Be Cool (where my son has the distinct honor of having a character named after him—Nick “Nicky Cadillac” Carcaterra). There are many lessons to be learned from reading an Elmore Leonard book and one cold hard fact that’s a take-away: he will never be topped.

He might have been the first to start a chapter in the middle of a conversation. “I thought George was,” Leonard told me, meaning George V. Higgins. When I asked Higgins the same question, he said, “I was pretty certain I lifted that from Dutch.” Others were watching as well. The opening scene of Lethal Weapon II begins in the middle of a car chase. “It’s nice to be read,” Leonard said.

He is gone now but the work will always remain, a reminder that for more than fifty years we were in the company of one of our greatest writers. There are the movie adaptations for those curious to see how they translate. They range from the horrible (both versions of The Big Bounce) to mediocre (Be Cool) to classic (Get Shorty and Hombre with Paul Newman and Richard Boone, one of Leonard’s favorite actors). “He’s got the look,” he said of Boone, “and he’s comfortable with the words.”

And then there’s Justified, sadly going into its final season. Every episode, practically every scene, is a tip of Timothy Olyphant’s hat to Leonard. Watching that show comes a close second to reading the work itself, it is that good and true. Raylen Givens may well end up being one of Leonard’s greatest gifts to us.

I miss Elmore Leonard. Miss hearing that sweet, humble voice that never surrendered to ego or brag, easy to smile, quick with a story, faster with a sharp line. It was an honor to be in his company, even for a short time. But he leaves behind a massive body of work that will age well with each passing year. The stories fresh, the characters memorable and the dialogue always true.

The lessons of the Master on the page, waiting to be learned.