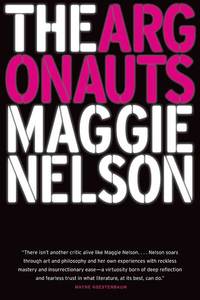

For the relaunch of our series of blog posts by contemporary fiction writers, essayists, poets, and historians, we reached out to Maggie Nelson to learn what classic works of American writing might have influenced her critically acclaimed new memoir The Argonauts.

The Argonauts—a book whose form tests the boundaries of genre at the same time its content pushes against traditional gender definitions—has been called “vibrant, probing, and, most of all, outstanding” by NPR, and “a beautiful, passionate, and shatteringly intelligent meditation on what it means not to accept binaries” by the Chicago Tribune.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time. If you’re looking for an example of how to move between personal anecdote, trenchant political analysis, and urgent spiritual/ontological rumination, I doubt anyone bests Baldwin. His account of his meeting with Elijah Muhammad was, is, endlessly instructive to me, not only for its use of an encounter as a springboard for reflection, but also for Baldwin’s skill in saying exactly what he wants and needs to say without bending under the pressures of imagined readerships, some of whom might stand all too ready to misuse his critique. (I thought about this issue a lot when trying to figure out how to weight various critiques in The Argonauts.)

Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Essential Writings. People love to talk about unclassifiable creative nonfiction as a recent invention, but what on God’s green earth are Emerson’s essays? Genre-wise, and sentence by sentence, they are some of the strangest, most inspiring pieces of nonfiction that I know. (Nietzsche thought so too—how’s that for mind-blowing.)

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua. First published in 1981, this collection feels fresh, relevant, and necessary every time I pick it up. Whenever people complain to me about the so-called “ivory towerness” of theory, I advise them to revisit the “theory in the flesh” articulated in these pages, which proves how some—perhaps most—people who come to analyze the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality do so out of a need to make livable lives, and sometimes to survive.

David Wojnarowicz, Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. I read this book when it came out in 1991. I was eighteen, and had just come of age in San Francisco, a city ravaged by AIDS, but I hardly knew what the hell had happened, what was happening. This book helped me to understand everything—about AIDS, about the brutality of normalcy, about how rage might be mobilized to sublime effect in writing, about queerness, about mortality, about friendship, about how hallucinogenic, poetic accounts of roadside encounters might be paired with utterly fierce condemnations of this country’s politics, and so much more.

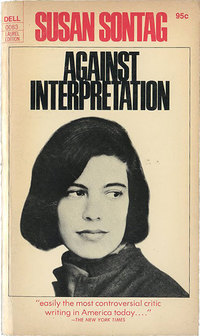

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation. Whenever I go back to my heavily annotated copy of Against Interpretation, I am appalled at how much of my thinking, and even my sentences, seem to me cribbed from Sontag. I guess I read Against Interpretation—an American classic of criticism if there ever was one—at a particularly molten moment in my development, when I was trying to figure out how to combine art and literary criticism, philosophy, and a certain speed or heat in my writing style. Sontag was so clearly already driving that car. I got in, and the rest is history.

Wayne Koestenbaum, My 1980s and Other Essays. Koestenbaum was my teacher once, and I remember very clearly his telling me: You have to get yourself to say upfront the unspeakable, indefensible thing; after that, you can spend the rest of the piece backpedaling or devoting yourself to nuance. But at least you’ve said it. I am endlessly in thrall to his mastery of this skill: his unsurpassable talent for assertion—hilarious, provocative, or perverse assertion—coupled with an appetite for / apprehension of nuance. I am edified by the range, verve, experiment, and energy of this collection, which makes me think there is a version of “American letters” that I could get behind.

Maggie Nelson’s previous books include several volumes of poetry in addition to The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011), a work of cultural criticism named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times. Nelson lives in Los Angeles and currently teaches in the School of Critical Studies at CalArts.