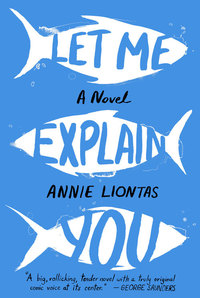

Our series of guest blog posts by writers of fiction, history, essays, and poetry continues today with a post by Annie Liontas, whose debut novel Let Me Explain You arrives this week. Slate calls Let Me Explain You a “sly and generous debut novel,” and Mary Karr has welcomed it as “a hilarious, fascinating, poetic work of fiction.”

Below she describes some of the key influences on her book, which recounts the travails of a Greek-American family in New Jersey.

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides. In writing Middlesex, Eugenides is said to have drafted 50 pages in one voice, picked up a new voice for another 75 pages, grown dissatisfied, and started over again. He did this for about nine years. For Eugenides, the narrative “had to render the experience of a teenage girl and an adult man, or an adult male-identified hermaphrodite.” This was further complicated by Eugenides’s desire to relay “epic events in the third person and psychosexual events in the first person.”

I could not have written Let Me Explain You without Middlesex. It was Middlesex that helped me solve the problem of structure in my own novel, and it was Middlesex that gave me a sense of scope. Middlesex confirmed my voice: it suggested I might have something to add to the conversation, even when scores of others have said their piece with far more eloquence. I am so intimately bound to Middlesex for its beauty, humor, and painful knowing of what it means to be foreign in our own bodies.

And maybe I steal a little bit of Desdemona for myself.

White Teeth by Zadie Smith. Any self-respecting immigrant novel pays homage to White Teeth, which works diligently to allow a multiplicity of voices to speak (this may be the very definition of an immigrant novel). Smith has a wonderful ear for how people talk and for what language sounds like when it’s making its home in a new country.

Smith wasn’t an immigrant herself, but she grew up around people “who had that experience, who felt separated or cut in two, who had moved from one country to another, who had the sense of leading two lives.” In White Teeth, the children of immigrants resist immigrant parents and claim their lives for their own, sometimes at a great price: assimilation brings alienation. In Let Me Explain You, this experience of exile—xenitia—visits a cost on the daughters of Stavros Stavros Mavrakis.

But White Teeth is funny, too. Smith says, “If I die and someone says, “She was a comic novelist,” I would be more than happy. My favorite writers are comic novelists. I don’t see any point in being anything else.” Me neither.

El Boom, particularly A Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez—which remains my favorite book—but also The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes. I sought out The Death of Artemio Cruz when I was deep into Let Me Explain You, and I knew that what I had on my hands was a proud, stricken, narcissistic patriarch. I was looking for versions of Stavros Stavros Mavrakis in other novels. I got as close as a shadow to Artemio Cruz, to the indignation and fear of death, to the spite that he wordlessly hurled at his wife and daughter, whom he knew to be selfish and concerned only with his estate. He smelled incense on his death bed.

I mostly hated him, but I had to pay my respects to a man not long for the world. Everyone deserves their dignity, especially at the end.

Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta by Aglaja Veteranyi.

Our story sounds different every time my mother tells it.—Aglaja Veteranyi

Aglaja Veteranyi, whom you probably never heard of, drowned herself in 2002 in Lake Zurich. A Swiss writer of Romanian origin, Veteranyi was part of a touring circus. Her stepfather was a clown and her mother an acrobat. She, herself, was made to juggle and dance. This is the subject of the novel Why the Child Is Cooking in the Polenta, which she published before she took her own life (other works released posthumously).

Vincent Kling notes in his exquisite afterward, having had the vision to translate the work into English, that Aglaja’s voice offers the “adult retrospective viewpoint but at the same time the child’s passage through successive stages of awareness.” Every line is touching, funny, or pained. Everything is true.

I read Polenta in a single sitting. I read it thinking, are you my mother? I read it thinking, you can be nobody’s mother. I stopped every few sentences to write something. I read and thought of all those stories of the old witch who fattens children up to eat them. I read Polenta and felt rage at not knowing the good-enough mother. I read it, and it helped me to write Litza as a child, suffering but resilient.

A graduate of Syracuse University’s MFA program, Annie Liontas won a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund and her short story “Two Planes in Love” was a runner-up in BOMB Magazine’s 2013 Fiction Prize Contest. For more than a decade she has dedicated herself to urban education in Philadelphia, Newark, and Camden, New Jersey.