An origin story that is near and dear to us reached the public last week with the publication of “Edmund Wilson’s Big Idea,” a detailed history of The Library of America’s founding by David Skinner that appears in the September/October issue of Humanities, the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, and online at neh.gov.

Skinner’s intricate, inside-baseball account makes it clear that the LOA had a long gestation period, stretching across decades—which perhaps isn’t surprising for a nonprofit literary enterprise. What may grab readers’ attention, though, is how close the Library came to not happening at all.

The original inspiration dates back to the 1950s, and to the critic Edmund Wilson, who had long complained of the lack of authoritative, readily available editions of seminal American authors. Wilson had in mind a U.S. equivalent to the French Bibliothèque de la Pléiade: reference editions of the classics in an inexpensive format. While he was able to recruit influential allies for his venture, his efforts to secure the necessary funding never came to fruition, despite the founding of the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1965. After that, years of competing proposals and various forms of academic and institutional politics kept his dream from becoming reality until the late 1970s, well after Wilson himself passed away in 1972. And even then, as Skinner shows, launching the project was a close-fought battle.

Skeptics argued that the proposed books would be too bulky. They would be too uncommercial—or they wouldn’t be scholarly enough. But years of tireless advocacy and shrewd politicking by the team who succeeded Wilson—“a rough synthesis of scholarship and New York City publishing brio,” in Skinner’s words—finally led to a Ford Foundation grant of $600,000 and a National Endowment for the Humanities grant of $1.2 million in early 1979.

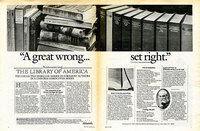

The rest, as they say, is literary history, and it would take an article at least as long as Skinner’s to do justice to the Library of America story since then. Its first four titles—collections of Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Walt Whitman, and Harriet Beecher Stowe—went on sale in early 1982, and years later Edmund Wilson himself entered the pantheon, via a two-volume set that amasses his essays and reviews from the 1920s through ‘40s. Perhaps the happiest note to conclude on is to mention that while in 1982 the first Library of America print ad [above] proudly predicted, “eventually the series will number more than one hundred volumes,” our upcoming James Baldwin: Later Novels, publishing later this month, is number #272 in the series.

Read “Edmund Wilson’s Big Idea” at neh.gov

(Note: since its founding The Library of America has not received regular funding from any foundation or government agency. Instead, it relies on grants and charitable contributions every year to supplement its revenue from sales.)