In connection with the publication in May 2010 of Shirley Jackson: Novels and Stories, edited by Joyce Carol Oates, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview for The Library of America.

LOA: Where should we place Shirley Jackson in the American canon? What was Jackson’s distinguishing achievement?

Oates: Shirley Jackson is one of those highly idiosyncratic, inimitable writers whose achievement is not so broad, ambitious or so influential as the “major” writers—Melville, James, Hemingway, Faulkner—but whose work exerts an enduring spell. Her “distinguishing” achievement is probably the famous story “The Lottery”—or the excellent suspense/Gothic novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

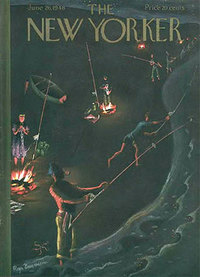

LOA: The volume includes Jackson’s very entertaining essay “Biography of a Story” which she frequently read before her public readings of “The Lottery.” When The New Yorker published “The Lottery” in its June 26, 1948 issue, the story generated more mail than any story the magazine has ever published. Was it really that different from anything published before? Why do you think it caused such a stir?

Oates: “The Lottery” is not so very different from brilliantly rendered and unsettling short stories by Edgar Allan Poe, for instance “The Tell-Tale Heart.” But it was published in The New Yorker, at that time far less than now a sort of bastion of proper middle-class/Caucasian-American values. The magazine tended to be prim, prissy, self-regarding, its tone annoyingly arch. Jackson’s story suggests that ordinary Americans—like the readers of The New Yorker, in fact—are not so very different from the lynch-mob mentality of the Nazis. Of course, Jackson’s vision of humankind is a bit simplistic and reductive, but hers is the art of radical distillation, like Flannery O’Connor, not subtly observed social drama like that of Henry James, Edith Wharton, or John Updike.

LOA: The Wall Street Journal recently referred to The Haunting of Hill House as “widely regarded as the greatest haunted house story ever written.” In his Danse Macabre Stephen King writes that “it and James’s The Turn of the Screw are the only two great novels of the supernatural in the last hundred years.” What sets The Haunting of Hill House apart?

Oates: This is possibly true—my preference is for We Have Always Lived in the Castle. However, The Haunting of Hill House is a highly engaging and suspenseful ghost story, that is, like all good ghost stories, an anatomy of its characters. Jackson’s “hauntedness” is in her troubled protagonist, not in the actual house—there is the possibility that a toxic individual is a contagion to others, and to herself.

LOA: In your review of We Have Always Lived in the Castle in The New York Review of Books you wrote that “of the precocious children and adolescents of mid-twentieth century American fiction”—and you include Frankie of Carson McCullers’s Member of the Wedding, Scout of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, and Holden Caulfield of The Catcher in the Rye—“none is more memorable than eighteen-year-old ‘Merricat’ of Shirley Jackson’s masterpiece of Gothic suspense.” What is it about Merricat that puts her at the top of this impressive roster—and why isn’t this remarkable novel better known?

Oates: Merricat has a sly, mock-naive voice that is very appealing, and very seductive, yet cruel and sinister as well. Listen to how she introduces herself:

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.”

The other novels are rather more “young adult” and “good”—their appeal is to a wider audience.

LOA: King notes that one of the motifs that Jackson uses in The Haunting of Hill House is to change the familiar Gothic “Bad Place” from a “womb” symbolizing sexual interest and fear of sex to a “mirror” symbolizing interest in and fear of the self. This question of whether what’s happening in the novel is psychological or supernatural—was this new with Jackson, or did she just do it better than most?

Oates: Shirley Jackson was much influenced by Henry James—you can register the Jamesian rhythms in her sentences—and so it is doubtful that she would have been drawn to write about the supernatural as an end in itself—only its psychological manifestations would be of interest to her. (In brief, this is the distinction between the “literary” Gothicist and the more popular Gothicist—in the latter, the ghosts are real.)

LOA: In A Jury of Her Peers, her overview of American women writers from 1650 to 2000, Elaine Showalter finds in Jackson the “three faces of Eve” that women writers in the fifties struggled with: the happy housewife, the intellectual and artist, and the “bad girl.” Jackson raised four children but was afflicted with depression, obesity, alcoholism, and agoraphobia. What do you make of the fact that she created her two masterpieces, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) and We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962), during the most troubled period of her life?

Oates: Writing—all art—is often compensatory for the artist. Think of the sequestered Emily Dickinson writing her incandescent verse while trapped in her “father’s house”—as she called it. Think of home-bound/house-bound/debt-bound Herman Melville writing Moby-Dick in rhapsodic desperation, far from the high sea that so inspired him. Jackson was not exactly abused or mistreated by her husband in any obvious way but Stanley Edgar Hyman expected Jackson to be his housewife-slave to a degree, and she had to find time for her writing when she could. (Hence, Jackson’s household was said to be very, very messy—overrun with cats!) She could not have been happy to know that her professor-husband had affairs with his Bennington students, who tended to adore him, while Jackson was stuck at home.

LOA: In a 1997 appreciation of Shirley Jackson on Salon.com, Jonathan Lethem pointedly remarked that, “She’s also terribly funny. Her observations are dry, her dialogue shockingly fresh and absurd, and her best stories can make you think of a collaboration between James Thurber and a secular Flannery O’Connor.” Do you see this as part of her enduring appeal? Does dry humor stay fresh the longest?

Oates: Jackson can be very funny in her “housewife” mode—see her domestic sketches: “Charles” or “The Third Baby’s the Easiest,” or “The Night We All Had Grippe.” She later revised these and included them in her bestselling memoirs of family life. In her darker mode—in stories like “The Daemon Lover,” “The Possibility of Evil,” or “The Summer People”—her humor is not so very evident. She seems almost literally to have had two personalities—in one quite large body—the one aiming for a popular readership of primarily women by way of the women’s magazines—the other the “Gothic” writer who perhaps wrote to please her own criteria, and did not aim for any particular magazine market.

(That “The Lottery” was published in The New Yorker is one of those happy accidents of publishing history. Another editor at the same magazine might have rejected it as too dark.)

LOA: In Private Demons, her rather chilling biography of Shirley Jackson, Peggy Oppenheimer quotes one of the rare statements Jackson made about her writing that tied together her interest in witchcraft and in eighteenth-century fiction (her favorite writer was apparently Samuel Richardson): “I have had for many years a continuing interest in magic and the supernatural. I think this is because I find there so convenient a shorthand statement of the possibilities of human adjustment to what seems to be at best an inhuman world.” Eighteenth-century novels she loved for “the preservation and insistence on a pattern superimposed precariously on the chaos of human development. I think it is the combination of these two that forms the background of everything I write—the sense which I feel, of a human and not very rational order struggling inadequately to keep in check forces of great destruction, which may be the devil and may be intellectual enlightenment.” Is seeing this heroic Manichaean struggle in the mundane details of everyday life the crux of American gothic? Doesn’t the dark side seem to be winning most of the time in Jackson’s work?

Oates: In individuals who find themselves powerless in life—like women, in general, before they were “given” the vote—there is always an interest in the occult since it circumnavigates the actual bastions of power. You will not find many men in high office—men with political/ financial power—who have an interest in witchcraft, for instance. Jackson was of this sort—she so lacked personal power, the (feminist) possibility of a subversive sort of power would engage her. Of course, this supernaturalism shades into fantasy, and this fantasy shades into mental illness, in some. The artist speculates on these matters without—ideally—sinking into them.

LOA: In the 1950s Shirley Jackson’s work seemed to appear everywhere: The New Yorker, McCalls, Redbook, The Saturday Evening Post, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Ladies’ Home Journal, among others. In fact, Linda Wagner-Martin seemed to be referring to Jackson’s ubiquity, rather than her influence, when she called the fifties “the decade of Jackson” in The Mid-Century American Novel. Lenemaja Friedman closes her book-length critical study of Jackson with “Miss Jackson is not, however, a major writer; and the reason is . . . that she saw herself primarily as an entertainer, as an expert storyteller and craftsman.” Why is being entertaining held in such low regard? Is Jackson’s work too diverse to be properly appreciated?

Oates: These questions of the canon are very broad. To be a “major” writer one must write “ambitious” novels, probably—one must cover a larger terrain than Jackson, O’Connor, Welty set out to do. One could not possibly suggest that Flannery O’Connor, for instance, is as “great” a writer as William Faulkner; but they are each excellent, in their own scale. A single nocturne by Chopin may be as exquisite as a Beethoven symphony, though its very brevity/smallness would probably preclude it being “great.” Such questions of canon—and scale—are matters of debate.

LOA: When did you first discover Shirley Jackson? Has her work influenced yours? Do you have any favorites in this collection?

Oates: One of my very favorite Jackson stories was an utter surprise to me—”Janice”—written when Jackson was an undergraduate at Syracuse University. It’s a gem, and previously uncollected. I also very much admire “The Intoxicated” and “The Daemon Lover.” Originally, it was “The Lottery” which I’d first read, as a girl, and very much liked. I don’t think that Jackson can be an “influence” on anyone—she was too quirkily original.

LOA: Jackson wrote many other works: two memoirs, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons; four novels, The Road Through the Wall, Hangsaman, The Bird’s Nest, and The Sundial; and several dozen stories. Might there be another Shirley Jackson Library of America volume?

Oates: It is possible that a second volume of the Library of America Shirley Jackson could be assembled, but I am certain that this volume contains the very best work, and certainly the very, very best short stories.