In connection with the May, 2007 publication of Philip K. Dick: Four Novels of the 1960s, edited by Jonathan Lethem, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview with Lethem for The Library of America e-Newsletter.

LOA: Of all the science fiction writers of the twentieth century, why is Philip K. Dick the one who—judging from the reissue of his novels and the movies made from his work—has most grabbed the popular imagination?

Lethem: He’s popular in a different way than any other writer. I call him science fiction’s Lenny Bruce. Coming out of the same tradition and using the same materials as other science fiction writers, he was in a sense science fiction’s answer to the Beat generation. He was the ultimate outsider, nonconformist, dissident. At the time he entered the field, science fiction was preoccupied with genuine scientific developments, space exploration boosterism, and a super-rational cognition. Where everyone else was writing about extrapolation and thinking hard about real possibilities, Dick was attuned to the unconscious, the irrational, the paranoiac, the impulsive. His stories had a wildly hallucinatory nature that he treated as if it were rational.

Now, the stories of the other science fiction writers were not as rational as they claim. They were quite in the grip of a fabulating imagination or wish fulfillment. They were writing fairy tales more than they acknowledge. But Dick engaged in the most direct and distinctive way with the undertow of terror and the irrational in contemporary technological society. That’s why science fiction was important to begin with, because it addressed the fact that we were living in a technocratic age when traditional arts, literary and otherwise, didn’t have much to say on this and didn’t find a lot of vocabulary for acknowledging the increasing rate of change and what it did to the experience of ordinary life. Science fiction in its clumsy, mawkish, embarrassing way was taking the bull by the horns.

LOA: Was he alone in this role or part of a movement?

Lethem: Early on he was more or less properly understood to be of a piece with a group of writers known as the Galaxy writers because that was the magazine in which they published. Robert Sheckley, Frederick Pohl, Cyril Kornbluth, William Tenn, and a number of other writers were nudging science fiction to a greater use of satirical, social commentary. They used satire to expose some of the traps, paradoxes, and perversities of consumer capitalism.

Dick did participate in this movement and he continued to be an acerbic critic of late capitalism. He saw what the advertising age could do to consciousness and in many ways he was extremely prescient on the subject of the invasive power of Madison Avenue, the way it was shaping the entire culture.

What Dick did was to take this movement’s tendencies toward social criticism and add to them this almost unbearably personal, emotional, intimate quality. His characters don’t just live in these paranoid futures. They are utterly at the mercy of them. As absurd and surreal as the images and ideas in Dick’s books could sometimes be, he always took them seriously. The predicaments of his characters were never funny to him. They were overwhelmingly terrifying and important. That’s what makes him so distinct, not only from other science fiction writers, but also from other postmodern satirical writers that he could be associated with, writers like Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, Donald Barthelme, and Richard Brautigan, all of whom also worked with absurdist and fantastic materials. Dick commits to his visions with an emotional intensity unlike any other writer. He digs deeper and makes a life or death commitment to the situations in his novels. His books always have this doubleness. There’s a layer of satirical or fantastical inventiveness—he’s one of the great idea men of all literary history—but there’s also this personal emotional stake. He’s always putting everything he has at risk. The characters are deeply vulnerable, deeply flawed, and at the mercy of their situations.

LOA: Is this because there’s less of a separation between Dick and his characters?

Lethem: There is very little separation between Dick and his characters. This goes back to the sense that Dick was a writer who in his process was impulsive, he was explosive, he was prolific and he was not utterly in control. And this is the reason there’s variation in the prose and is also the reason why some people find his writing awkward in some ways. He was writing with a kind of personal visionary intensity that didn’t make time for some of the niceties, some of the second thoughts and revisions that you might wish a literary writer to be able to make.

LOA: Many writers—Robert Heinlein, Stephen King—get this criticism: that their ideas and plots are better than their writing. Yet Dick’s prose seems to have a special charge.

Lethem: He’s such a deeply humane and intelligent writer, so committed, that the prose conveys a tremendous amount of meaning, even at its most awkward. I would say quite happily that the four books collected in Four Novels of the 1960s are among the most fully realized, the least infelicitous of his books. Ubik, which may be his singular masterpiece, has in its earliest chapters some wheel-spinning, some time-wasting material that can be a bit offputting to the uninitiated reader. And this isn’t to apologize for this but to acknowledge it and just say this is there. For this reason I’ve often had the experience in recommending Dick’s work to someone, that the second book they read is their favorite. Forever. Whatever the second one is. They read one and say, “Oh, this is a little odd, this is a little bumpy. I want to read more.” Then they somehow shift into the gear he is working in and they become a devoted fan, the second one in.

LOA: Are these Dick’s four best novels?

Lethem: It’s quite important to note that this volume is structured as Novels of the 1960s, which was my wish for a number of reasons. First and foremost, I want to leave room for Novels of the 1970s—there are at least three or four novels from that decade that would make a superb companion volume. If I had been forced to make a single volume representing the entirety of his career, it wouldn’t necessarily have been these four books. If you had to pick a single decade to represent his work, the 1960s is the one to pick. That is the summit, but in that decade there are at least four other novels every bit the equal of the four here: _Dr. Bloodmoney, Now Wait for Last Year, A Maze of Death, and probably the book that came closest to being included, Martian Time Slip. These are all superb novels, singular and fully realized and all from the 1960s, an incredibly prolific decade in which he wrote another ten or twelve books.

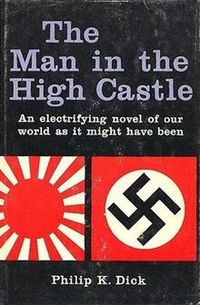

This volume is set up with the best introductory book by far. The Man in the High Castle is the first book and that is a very happy arrangement. The chronology demanded it but it’s perfect. It’s the book that draws people in and it’s the most embracing, particularly for a non-genre reader. It is also a work of extraordinarily passionate and scrupulous scholarship. This is not the daydream of someone who’s just wondered what if the Nazis won the war. All of the minor Nazi characters are thoroughly researched. Dick has written this almost scholarly alternate reality.

LOA: How do you account for his tremendous output? Was it just the speed?

Lethem: He certainly took a lot of amphetamines. Thinking about Dick biographically and thinking about his habits as a writer can be quite fascinating and perplexing because no one fact could ever account for the torrential quality of his work. There are several things you can point to—all partial explanations. Amphetamines is one. There is also something very interesting to think about in terms of his life. It can only be a speculation. He died eventually of a stroke. And it’s likely he suffered other near-stroke experiences in the preceding years, but there is some reason to wonder if he suffered from a rare neurological disorder called temporal lobe epilepsy, which has associated with it involuntary and overwhelming visionary experiences, and graphomania—frantic writing, compulsive writing. There is no way ever to ascertain this theoretical diagnosis and I wouldn’t want to sound too certain about it. But it’s very interesting to compare him with other famous cases of temporary lobe epilepsy. Because there are some striking similarities. And if you want to make some speculative diagnoses, there are connections you can make with other famous mystics and religious visionaries who are famous for their obsessive writing. St. Theresa of Avila is one. She saw extraordinary visions and then spent years scribbling endless explanations of these visions in fits of graphomania. Dick is a very provocative figure to think of in these terms. He’s an exemplary character for the strange, auto-didactical intensity of his work

LOA: You say that he was one of the Galaxy writers. Was that the only publication that responded to his work at the time he was writing?

Lethem: He was placing stories in a great variety of magazines in the early and mid-1950s. He was seen as a wunderkind at that point. He was part of the second generation of great American science fiction pulp writers and the only thing he didn’t manage to do—and it’s interesting to wonder if it would have changed his approach and what would have happened if he did—was to place a lot of stories with Astounding, which was seen as the leading magazine of the time and had a very brilliant and imperious editor, John W. Campbell. To place a story with Campbell was seen in science fiction circles as being analogous to placing a story with The New Yorker. It was the place to be published and Dick, for a number of complicated reasons, did not break into that market and didn’t receive the cultivation that Campbell gave to his writers. Isaac Asimov was the principal exemplar of the Campbell style and Campbell’s protégé. Looking at it now, you would say this was a slightly old-fashioned, more optimistic style. Campbell’s counterpart at Galaxy was Horace Gold, who was more literary. He was a New York Jew, and perhaps less sold on the great bold technocratic future of this country, more inclined to notice the undertones and mixed messages.

LOA: In your essay for Bookforum, “You Don’t Know Dick,” you recount your youthful experiences tracking down rare out-of-print copies of Dick paperbacks in used bookstores in Brooklyn. Someone discovering Dick for the first time in the Library of America edition is clearly going to have quite a different experience.

Lethem: It’s an amazing thing to think about: the journey that this writer has taken. You can’t help but wish that he could somehow know this is happening. It is a tremendous thought that he’ll be received by readers whose expectations are canonical by definition.

The conditions of my discovery of his work are very much time-bound. This was the late 1970s and early 1980s. We lived in a different, much less Dickian world then. What’s extraordinary about his work at the moment is how incredibly relevant it can seem and how much the world has caught up with him. That’s true in a general sense. The iconography of science fiction, the kinds of materials and images and kinds of metaphors he was exploring are quite commonplace in the culture now. Everyone is up to speed on what an android is. It’s not exotic. It’s a question of whether you do something interesting with it. No one’s going to be overwhelmed, or struck, or confused or put off. It’s simply part of the vocabulary of culture. And that was not true thirty or forty years ago. But also in intensely particular and peculiar ways Dick’s visions—though he wasn’t interested in being a predictive writer, and he wasn’t systematically trying to be predictive in his extrapolations—his instincts about where the media, where commercial culture were headed were unerring. We live in a world precisely full of the kind of invasive, mind-colonizing advertising, viral marketing notions that he predicted when it seemed absurd to do so. We really live in his universe, in his brain in a way. It’s not just that now he’s going to be in a Library of America edition. Someone coming to read his work now for the first time will feel bewildered by the copyright dates on these books. They will be reading so much about the world we live in, in a peculiar and weird form, but finding it utterly relevant and fresh.

LOA: You say Dick did not see himself as a predictor of the future. What was Dick’s vision of himself?

Lethem: His image of himself as a working artist is a very complicated question. He had tremendous and thwarted aspirations to be recognized as a literary writer and he considered himself a failed writer in that regard. Yet in other ways he felt that he had accomplished—and I think rightly—great things in this despised form and that they had gone unrecognized. He alternates between thinking that he lost his chance and that he had seized his chance but that no one knew. At other times he was defiantly proud of the genre of science fiction and felt it was an antidote to the conformity, the blandness and the tendency of the mainstream not to examine the status quo. He felt like a rebel and was proud to be one. He was not particularly interested in some of the usual things that science fiction was thought to be meant to do, like prepare people for the future or predict the future. He was a fantasist and a storyteller and his extrapolations were satirical ones of the present rather than predictions. Yet paradoxically, in their accuracy, their vividness, the hints of the reality he saw embedded in the world of the 1950s and 1960s, by extrapolating and satirizing them, he did accurately predict the future quite neatly.

LOA: Did Dick see himself as a stylistic innovator?

Lethem: I think the radicalism in his work does not operate in the way writers or critics usually think of as style, which is to say, the choices made sentence by sentence. But there is a formal radicalism to his work in the way he structured his novels, the way he composed scenes, the way he advances stories, the way he conflates disparate kinds of material, different tones like despair and satire— that’s the level at which there is a conscious and proud experimental, radical, innovative effort being made. It’s not exactly what one normally thinks of as style. It’s more a matter of form and motif.

LOA: Did Dick consider himself part of an American tradition of fantastic writing, dating back to H. P. Lovecraft?

Lethem: It’s almost a parallel formation in American fantastic writing. When, in the mid-1930s, science fiction writers began to articulate the genre, they derived some strength from their comradeship or their awareness of the Lovecraftian horror and fantasy writers. They also defined themselves somewhat in opposition. Fantasy was a dark and dreamlike kind of writing and the science fiction writers thought they were doing a lucid and optimistic kind of writing. This opposition may not seem so simple in retrospect. They were allied traditions, allied by their distance from the mainstream of literary credibility. They were also opposed to one another at certain fundamental levels.

Dick never made any specific comments about Lovecraft that I’m aware of. There are some deep native tendencies they have in common. Dick dabbled in what the science fiction writers of the time considered the fantasy genre two or three times. There is one novel, The Cosmic Puppets, and several quite accomplished short stories—in particular, “The King of the Elves” and “The Father Thing”—where Dick is deliberately writing as a fantasy or horror writer rather than as a science fiction writer. Dick would have seen these as a conscious migration across a “membrane” into another field of operations. These traditions now seem so interrelated that these distinctions don’t seem that important.

LOA: Dick is so popular with filmmakers now. At the time he was working many science fiction writers—Ray Bradbury, Rod Serling—were having teleplays produced on television. Did Dick ever try this?

Lethem: That was a ticket he could never buy for himself. He tried a few times. Because for a starving artist as he was it seemed like it might be a meal ticket. But he didn’t have the ability to shoehorn his wild visionary style into a 30- minute television format. His few attempts were charmingly hopeless. He only wrote one screenplay, an adaptation of Ubik. Again, it was charmingly hopeless. It could never have been filmed in the form he wrote it. In his papers were found a few synopses for TV shows where he was obviously trying to market himself. They’re much too interesting and eclectic and too full of stuff. His principal misunderstanding is that he couldn’t simplify to the level he would have had to. They’re quite overcomplicated and brilliant and nothing like the 1960s science fiction television that we remember.

LOA: The Library of America volume includes your notes. May we assume that nothing like these appeared in the original novels, no translations of foreign phrases?

Lethem: Yes, the notes are all brand new and the phrases were untranslated in previous editions. I added a few cultural references. Some things I never completely understood and some things seemed quite specific and needed explication. Just as a Dickens novel has to be annotated for things that would have been completely lucid to readers of his time, these are starting to be older novels and there are some cultural references the reader might like some help identifying. Radio comedians of the 1930s might have seemed easy names to drop in the 1960s. Fifty years from now we can hope Jim Carrey will be a difficult name to recall.