The Library of America notes with sadness the death, on December 22, of literary scholar Lewis M. Dabney (1932-2015), an authority on the life and work of critic Edmund Wilson who edited our two volumes Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 30s and Edmund Wilson: Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1930s and 40s.

In Dabney’s honor we now republish the following interview with Rich Kelley for Library of America when the two Wilson collections were released in October 2007. (This interview had previously only been available as a downloadable PDF on loa.org.)

LOA: Was Edmund Wilson, in the words of The New York Review of Books, “the preeminent American man of letters of the twentieth century”?

Dabney: That’s true. Wilson wrote important essays and reviews, reportage, memoirs, journals, and history as well as his own fiction, poetry, and plays. But it may not be the most useful characterization. This literary journalist produced more influential and apparently more permanent criticism than have a good many of the then-reigning American academic critics and their successors, the theorists. I prefer to think of Edmund Wilson as the major critic of the twentieth century, which includes his work as cultural and social historian. Because he wrote for the general reader, not for specialists, English departments have often denied him that title, and since so much criticism since the 1940s has been close reading or abstract analysis, Wilson was happy to call himself a writer and a journalist. He started life as a cub reporter and worked up stories as journalists do. As a man of letters, he wanted people to be interested in his poetry, fiction, and plays, as well as his autobiographical writings.

LOA: These two volumes include his writings from 1920s, 30s, and 40s. Do these volumes contain all of his work from this period?

Dabney: They encompass his literary and cultural writing of this period, while his reportage and political writing will appear in forthcoming Library of America editions. The first volume contains The Shores of Light, a retrospective collection of reviews published in 1952, and Axel’s Castle, published at the end of the 1920s, his most important book of that decade. Our second volume includes the critical essays of The Triple Thinkers and The Wound and the Bow, written concurrently with To the Finland Station, the great history of Marxism that followed Wilson’s years of reporting on the crisis of America in the Depression. Volume Two ends with a second collection of short pieces, Classics and Commercials, reflecting the very different cultural milieu of the 1940s. Each volume includes well-known memoirs of his teachers and youthful literary friends—Christian Gauss and Edna St. Vincent Millay in The Shores of Light, his prep school Greek teacher in The Triple Thinkers, and Paul Rosenfeld in Classics and Commercials, which also contains “Thoughts on Being Bibliographed,” Wilson’s mid-career retrospect of the 1920s and 30s.

LOA: Wilson’s career as a writer began in 1919 when at 24 he submitted a parody to Vanity Fair and Dorothy Parker took notice of it. A year later he replaced Robert Benchley as managing editor of Vanity Fair. In 1925 he began writing for The New Republic and he served as its literary editor from 1926 to 1931. Then in 1944 he became the weekly book reviewer for The New Yorker, where most of his work of the next 25 years appeared. How much did the magazine in which his work appeared affect what he wrote?

Dabney: Significantly. For the first four or five years of his career Vanity Fair gave Wilson a platform and a way to publish his friends. It was an uptown job from which he could sashay forth into bohemia to achieve another kind of self. But from the very beginning friends like Scott Fitzgerald felt he needed a more serious venue. So did Wilson, and he found this at The New Republic. In New York City between the wars, The New Republic, committed to what its editor Herbert Croly had called “the promise of American life,” achieved a position in the literary world that no magazine today quite has. Lionel Trilling, a critic some years younger, felt that the fact that Wilson appeared in almost every issue for six or eight years—and sometimes twice—(an enormous amount of writing) helped to form his voice and give him his authority. Wilson’s first New Yorker phase, which we have in Classics and Commercials in Volume Two, afforded him a much larger, more disparate audience. With the American literary and intellectual movement of the 1920s apparently fading, he divided his interest between “classics,” many of them British comedy and satire, and “commercials,” exercising his own satiric instinct on work that he thought ephemeral, from detective stories to women’s bestsellers.

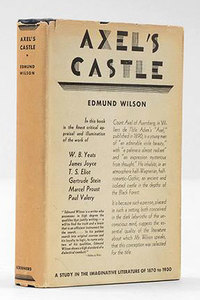

LOA: Volume One includes Axel’s Castle, Wilson’s first major work of criticism, featuring chapters on Joyce, Proust, T. S. Eliot, Yeats, and Gertrude Stein. Yet Wilson is not considered a modernist. Why did he group these writers together?

Dabney: Wilson was a critic who explained subjects and interested readers, a storyteller, a master of exposition and compressed intellectual analysis. We associate literary modernism with experimental fiction and poetry, with the grand novels of Joyce and Proust, with Eliot’s “The Waste Land” and its influence, with Yeats’s evolution from a late Romantic fairyland to the exploration of life and death, youth and age, alongside the public world in the greatest verse of the 20th century. As Wilson reviewed these writers he saw in them techniques and attitudes he called symbolist. These excited him, as did the experimental style of Hemingway’s In Our Time, of which Wilson wrote the first American review. He emulated Joyce and Proust in his unsuccessful first novel, I Thought of Daisy—more widely read today than it was in the author’s lifetime. He played a central role in passing these experiments on to the educated public. Wilson didn’t like the word modernism, but that’s another story.

LOA: Volume Two includes two major works of criticism with provocative titles, The Triple Thinkers and The Wound and the Bow. How do the titles relate to what he was trying to do in these works?

Dabney: The Triple Thinkers comes from a quotation from Flaubert in a letter to his friend Louise Colet. “What is the artist if he is not a triple thinker?” The artist should be able to see a long, long way. Wilson wrote these essays on nineteenth- and twentieth-century figures at a time when his efforts on the American left and his belief in Marxism had run up against certain barriers. He could still rely on literature and the writer. In his essay on Flaubert’s politics he shows the French novelist seeing the darker possibilities of socialism as Karl Marx could not.

The Wound and the Bow is an even more resonant title and springs from Wilson’s belief that art comes out of suffering and struggle. It’s a title that concentrates his thinking about artists he had known and lived among and his knowledge of literature going back to the classics. The title essay concerns Sophocles’s play Philoctetes, and incorporates several different ideas. One is the idea of suffering being resolved or ameliorated by artistic form. The second is the romantic idea of the artist as apart from and alienated from society, needing to be restored to it by the value of his work. Wilson absorbs the Freudian idea of art and neurosis into this larger frame. Neurotics don’t necessarily make great artists, but he thought that great artists can use their personal difficulties and the lack of order in their inner and outer worlds to try to create form. The seven studies in The Wound and the Bow variously explore these themes. Some people think this his best book of literary essays. Axel’s Castle is absolutely brilliant on Proust and Joyce but uneven on one or two of the other moderns, while The Triple Thinkers covers more subjects and is not so tightly unified.

LOA: The critic Alfred Kazin once wrote that “in every subject [Wilson] saw a career, a personal leitmotif, some primary tension. This appeared most explicitly in The Wound and the Bow, where the study of writers so diverse as Dickens and Joyce, Casanova and Kipling, Mrs. Wharton and Hemingway, revolved around some childhood wound in each writer which led him to become the writer he was.”

Dabney: That’s an excellent summation of the theme, yet it’s not entirely accurate. The childhood wound is there with Dickens and Kipling and they are more than half the volume. But Wilson is careful not to push a biographical emphasis without real evidence. If Joyce had a wound, perhaps it was his going blind and the compensating bow might be his ear, but that is neither Freud nor alienation from society. With Edith Wharton, Wilson is handicapped by a lack of knowledge. Many critics have suspected a childhood wound in Wharton but we still have no firm knowledge of one before her marriage. While Hemingway was clearly wounded by his parents as well as World War I, Wilson is careful not to use these well-known facts when establishing the qualities of Hemingway’s writing. He offers a convincing account of Hemingway’s ups and downs as a writer: X book is wonderful, Y is pretty good, Z self-indulgent or silly. Hemingway greatly resented this sweeping appraisal by the critic who had established his importance in the early review of In Our Time. He would have resented it more, and justly so, had Wilson tried to explain all this biographically.

LOA: Wilson was prescient in appreciating the value and importance of several significant writers. He wrote the first serious review of “The Waste Land” and of Ulysses. He’s also credited with mentoring and helping to bring recognition to the work of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, Gertrude Stein, and Vladimir Nabokov. How much credit should we give Wilson for calling attention to these writers?

Dabney: I think it varies. His relationships with Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, and others are a theme of The Shores of Light. He defines Hemingway’s style in the famous interchapters on World War I and calls In Our Time the best book about the war by an American. With Fitzgerald the case is more complex. He did not have to get Fitzgerald noticed, but the early essay in Shores suggests Wilson’s huge influence over the five years between the college novel This Side of Paradise and The Great Gatsby. Wilson and Dos Passos were peers and comrades. They marched from the 1920s into the 30s, Dos Passos leading the way. When Russian Communism lost its moral authority, they turned away from it, Dos Passos again slightly ahead and going much further to the right. But Dos Passos was then much better known than Wilson. It was he, by then a hero in Russia who, when Wilson went to the Soviet Union in 1935, wrote to Maxim Gorki to get his friend’s visa application past suspicious bureaucrats.

Gertrude Stein was a major writer when Wilson was in college. During the early 1920s, he pleased her by promoting her achievement, but in Axel’s Castle, completed after the stock market crashed and as the Depression dawned, he thinks Stein too isolated in her narcissism. To look ahead to his later career, the short review of Nabokov’s book on Gogol in Classics and Commercials was written when Wilson had taken the Russian novelist under his wing, was promoting his work with magazines, getting him a Guggenheim, and so on. Wilson set up Nabokov’s whole American career, but the two friends, who enormously stimulated each other, fell out after Nabokov’s great success with Lolita and Wilson’s critical review of Nabokov’s literal but pretentious translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin.

LOA: Wilson was also responsible for cheerleading the rediscovery of several American authors.

Dabney: He was. He loved to discover “minor” writers whom no one else had noticed in any serious way. There are several in his later book, Patriotic Gore: Studies in the Literature of the American Civil War, which The Library of America will likely at some point get to. In The Triple Thinkers he brings back the noble figure of John Jay Chapman, a genteel fighter for progressive causes and writer of high-minded criticism who was both neurotic and brave and who, in the late 1930s, Wilson thought had something in common with him as well as with his father, Chapman’s contemporary. In the 1920s, Wilson was more alert than some Americans to the significance of Poe.

LOA: He seemed to offer a corrective view of Poe, whom other critics of the time treated as something of a freak.

Dabney: That was true. Poe had influenced Baudelaire, and young Wilson noted that Poe had something in common with the international poetic movement, which Wilson identified as evolving from French Symbolism. Poe was a romantic with the French appetite for technique and for talking about it.

LOA: Wilson wrote several pieces about Henry James, who seems to have been something of a touchstone for him.

Dabney: James appears in The Shores of Light as well as in the famous essay focused on “The Turn of the Screw” in The Triple Thinkers and in an uncollected review at the end of the second volume called “Henry James and Auden in America.” He was important to writers of the 1920s. When Eliot wrote to Fitzgerald about the success of The Great Gatsby he said it was the first step that the novel had taken since Henry James. For young Wilson, as for his friend, the poet Louise Bogan, and for Hemingway, James was a hero of art who confessed to not having lived enough and whom they thought sexually repressed. James remained for Wilson an American who had mastered, as Wilson always tried to do, the great work of the larger world and of England while maintaining a firm American identity.

Wilson was a literary patriot. His horizon was very American, and he resented any snobbish Old World airs of supremacy. But he was never a chauvinist. He was committed to absorbing the best stuff in the world into our culture and quite lacked what he later came to see as a parochial tendency within the American studies movement. He believed that writers should be taken within their national cultures, and he loved studying languages.

LOA: Lionel Trilling, whom you mentioned, was another critic who valued Wilson’s work highly, but took issue with his opinions of certain authors. Do you find that there are authors that Wilson didn’t get right?

Dabney: Everyone agrees that Wilson’s writing about the poets of his time was sometimes not as good as that about prose writers. He was better on Eliot and Yeats in the early 1920s than in 1931 in Axel’s Castle, and we’ve included wonderful, uncollected reviews of these poets at the end of Volume One. Another piece that people have reservations about is “A Dissenting Opinion on Kafka,” which was written at a time when the Kafka cult was almost overwhelming. This piece has been sometimes said to reflect Wilson’s inability to sympathize with a writer who lacked his own commitment to will and reason winning the day. It was constitutionally difficult for him to respect the defeatism and nihilism he detected in Kafka and one or two other European writers.

Wilson’s at his best when he’s in sympathy with his subject. The author of the short piece in The Shores of Light about Lady Chatterley’s Lover knows Lawrence’s work and can give to this book its value within the novelist’s development even as he pays tribute to Lawrence’s breakthrough in writing about sex, an advance upon both Joyce and Havelock Ellis. He praises Lawrence for taking the risk for other writers and kids him a little by noting that Lawrence’s “lovers are made to decorate one another with forget-me-nots in places where flowers are rarely worn.” Wilson’s authority in this review comes not alone from his critical gift: when he wrote it he was trying to deal with sex in a private journal in an even more daring way than Lawrence was able to do in a novel.

LOA: The contents of these volumes certainly testify to a wider range of interests than most literary critics have: essays on burlesque shows, detective fiction, John Barrymore, etiquette, stage comedies, bestsellers and their formulas, Houdini and other magicians. Was there any rhyme or reason to what he chose to write about?

Dabney: Being able to rove shrewdly across literature, history, and popular culture was one aspect of fighting the good fight in the trenches of American literature in Wilson’s time, a role more vivid to us at the present moment when the survival of book reviewing in our newspapers is seriously threatened. Wilson had a strong theatrical instinct. He dramatized personality and society in his criticism, and he loved the popular as well as the legitimate stage. In his own way he is writing for the stage in “A Preface to Persius,” the 1927 piece that develops his partly romantic, partly classic view of the tension between life and art and places this in the American scene. Subtitled “Maudlin Meditations in a Speakeasy,” this is a seminal article, as Professor Trilling emphasized to me at Columbia.

As a young man in the 1920s Wilson was drawn to vaudeville and burlesque, while he was burning the midnight oil at home. The Shores of Light conveys the beat of Jazz Age New York. This book salutes creative personality. The two pieces on Houdini treat the magician and escape artist as an heir of the Enlightenment and master of his medium. By contrast, the popular literature surveyed in the chronicle of the 1940s was manufactured for a mass market. Wilson’s well-known attacks on detective fiction defend standards not merely in this genre—as when he looks back at Sherlock Holmes—but in literature generally. When the young author of “A Preface to Persius” contemplates the “bulky pink people” banging into his narrator at the door and reasserts his literary credo, he can count on Proust and Joyce and “The Waste Land” as allies. In Classics and Commercials, Wilson retreats to the standard of British comedy, as I said before. He writes brilliantly about the early novels of Evelyn Waugh, also about the forgotten comic novels of Thomas Love Peacock, Shelley’s father-in-law. But the great liberating movement of the 1920s is gone.

LOA: Wasn’t it also that his friends who had represented the promise of the 1920s were dying around him?

Dabney: Absolutely. They were dying off. Fitzgerald died in 1940 followed in a few days by Nathanael West. Sherwood Anderson had died first. All the great men of the age—Joyce, Yeats, Freud, Trotsky (Wilson wrote to a friend)—had died at the same time. There was a sense of a world gone. And people who he thought were going on, like Edna Millay, did so in an isolation that in her case, when he visited her after World War II, he found both poignant and depressing—an all-too-visible wound without much of a bow.

LOA: You are the author of the widely praised intellectual biography Edmund Wilson: A Life in Literature, published in 2005 by Wilson’s publisher, Farrar, Straus & Giroux. In fact, I understand that it’s about to come out in paperback in October from Johns Hopkins University Press. How did you become involved with Wilson?

Dabney: I had been encouraged by a couple of my professors at Columbia, including Lionel Trilling and F. W. Dupee, to write a book on Wilson after I did my dissertation on his early work, and I was fortunate enough to meet him when I was teaching at Smith College. He spent some time with me over dinners and, liking my review of Patriotic Gore, invited me to the old stone house in upstate New York for four days. I was being looked over as a potential biographer, although neither of us alluded to the subject. I came back to Wilson well after his death and later in my own career. I’ve been the beneficiary of a lot of people who loved Wilson and knew him. I collected their impressions with the backing of Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, who was his publisher for the last twenty years of Wilson’s life and became my publisher and sponsor for the twenty years the biography took.

LOA: Finally, many people may not be aware of Edmund Wilson’s role in conceiving The Library of America. Could you describe what he did?

Dabney: In the early 1960s Wilson had the idea that there ought to be an American series like the French Pléiade, which should be well edited, without too much apparatus and long professorial introductions, designed to get the national literature read. He shared this project with Jason Epstein, who published four of Wilson’s books in the first ten of the Anchor series. There was interest from various people, including President Kennedy. Nothing came of it, partly because the Modern Language Association was agitating to edit the American classics in a much more academic way and, as Malcolm Cowley told me, had more political power because they were represented in universities across the country (Wilson satirized some of their literary methods in “The Fruits of the MLA”).

What eventually happened is that the Ford Foundation offered $500,000 to its retiring head McGeorge Bundy, for any project Bundy proposed, and Bundy dedicated this gift for The Library of America. Matching funds were provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities and various professors, including Daniel Aaron and Richard Poirier, were brought in to take charge. That early generation (from more than one of whom I have heard details of this story) was very much aware of Wilson’s role. We are all beneficiaries of these wonderful editions.