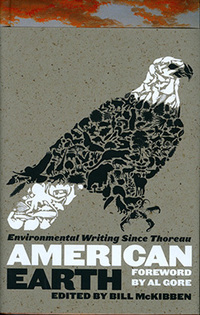

In connection with the publication in April 2008 of American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau, edited by Bill McKibben, Rich Kelley conducted this exclusive interview with McKibben for Library of America.

LOA: In your introduction to American Earth you suggest environmental writing might be “America’s single most distinctive contribution to the world’s literature” and that environmental writing overlaps with but is different from “nature writing.” What is the difference?

McKibben: In American Earth I’ve focused on writing that really gets at some of the conflicts between people and the natural world, and not just the appreciation of the glories of nature. Environmental writing asks searching questions about what happens when people collide with the rest of the world. What are the effects? Are they necessary? Might there be a better way? While it often celebrates nature, environmental writing also recognizes that nature is no longer innocent or invulnerable.

Take a writer like Thoreau, who spent many hours every day outdoors and was a fine botanizer and natural historian. He meets anyone’s definition of a naturalist. But he was much more: argumentative, eccentric, perhaps most of all deeply sensitive to the human culture around him. He was struck by the idea that the lives Americans had begun to lead were desperately divorced from reality, a reality that could be found in nature. “In wildness is the preservation of the world,” he wrote famously—one of the great koans of American literature. He asks the twin questions that have become far more acute in the 150 years since his passing: “How much is enough?” and “How do I know what I really want?” Nothing about the age of McMansions, SUVs, or 500-channel cable systems would have surprised Thoreau.

LOA: The selection process for American Earth must have been rigorous. The book runs almost 1,000 pages and yet, except for Thoreau, no writer, whether Rachel Carson or John Muir or John Burroughs or Wendell Berry—gets more than 30 pages. What criteria did you use in selecting pieces for inclusion?

McKibben: It was an impossible job and a painful one, and the book could easily have been five times as long. But I was most interested in chronicling the development of ideas over time—of wilderness, of community both biological and human—great writing and thinking; great influence over events; preferably both.

LOA: You note in your introduction that the environmental movement was often driven by a piece of writing and the book includes Tom Turner’s splendidly detailed timeline of the movement’s achievements. Can you cite some of the more significant examples of this connection between words and events?

McKibben: Without George Perkins Marsh and his observations on the dangers of deforestation, it’s not at all sure that the New York State legislature would have embarked on the extraordinary task of protecting the Adirondacks. Without the ecstatic prose of John Muir, who invented a new grammar and vocabulary of wild delight to describe his afternoons in Yosemite Valley, it’s hard to imagine that the Sierra Club would have emerged to lead a century’s worth of battles. Without Rachel Carson sounding the alarm when she did, it seems entirely likely that many more species of North American birds might have been doomed. And there are many others: Aldo Leopold and game management, Jonathan Schell and the nuclear freeze, Michael Pollan and the local foods movement, Al Gore and global warming. Each advance in environmental practice was preceded by a great book, a procession perhaps unique in American letters.

LOA: Some people may think that a collection of environmental writing must be filled with scientific papers on changes in CO2 levels or reports from the International Panel on Climate Change. Yet there is only a single graph in American Earth and it has a distinctly literary flavor. Is environmental writing more effective—or perhaps just more memorable—when it has less scientific detail?

McKibben: There’s actually plenty of reference to science, from George Perkins Marsh on deforestation to Rachel Carson on DDT to Sandra Steingraber on the newest plague of chemicals. But the work of scientists needs translation—not just literal translation, but emotional translation. Science and literature have actually worked very well together over the last century in this country.

LOA: Joseph Lelyveld’s account in The New York Times of the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, occurs at about the halfway point in American Earth, which means that most of the selections date from the last 37 years. What is it about the writing from this period that warrants its large representation? Is it more urgent, more relevant?

McKibben: The more the earth comes under siege, the more clarion voices rise to its defense. There seems to be an almost inverse relationship between ecological decline and powerful voices. The writing just keeps getting better, in part because it comes from a much more diverse spectrum. Early environmental writing often has a patrician streak—now it’s everyone in the game. Including women, which has been a great improvement literarily. Many are activists as well as writers and they are doing the necessary work of seeking out ideas and images that will help America, and then the world, to confront the very much deeper problem we now face. They are interested in far more than description. What’s key to understand is that this new generation of environmental writers rose to prominence in the years since 1980—the years since Ronald Reagan took office and the longstanding bipartisan commitment to environmental reform collapsed. In a globally warming world we now know that it does no ultimate good to set aside a wilderness area if you don’t also preserve the climate that makes it what it is. Environmentalism can no longer merely fix the excesses of our consumer culture. It needs to change that culture.

LOA: American Earth features wonderful entries by many of the writers we expect to find here—Thoreau, John Muir, John Burroughs, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold—but there are also quite a few delightful surprises: novelists Theodore Dreiser and John Steinbeck, Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, César Chávez, R. Buckminster Fuller, Jane Jacobs, Philip K. Dick, Joni Mitchell, Russell Baker, even cartoonist R. Crumb. Is this inclusiveness a way of saying that we need politicians, poets, and pranksters to create the ideal community of the future?

McKibben: The most recent data show Americans far less satisfied with their lives than people in many other places, most of them poorer than we are. The reason seems to be our sharply felt lack of community, of connection with others. Much recent environmental writing is about rebuilding that community. I think a lot about movement building, because it’s largely what I’ve worked on for the last few years. (I’ve helped organize about 2,000 global warming demonstrations in the U.S. with StepItUp; now we’re trying something global with 350.org.) I think movements need more than earnestness; they need fun, music, creativity, art, sass.

LOA: In 1989 you published The End of Nature, the first book about global warming written for a general audience. Many of your books, like Fight Global Warming Now and Deep Economy, have been how-to handbooks for activists, and you are a well-known activist responsible for galvanizing thousands into action for environmental causes. What role can a book of writings like American Earth play as part of the environmental movement?

McKibben: It can help ground us in the history of this fight, so we realize what mistakes have been made and also what great resources and tradition we build on. Every environmental campaigner follows John Muir in his defense of Yosemite, for instance—to read his language is to understand how to rouse people. Of all the images and metaphors that have fueled environmentalism in the past the most important has been that of the wild. The wild, the pure, the clean: from Thoreau to Abbey, from Muir to Austin to Brower, that’s been the key idea, the emotional trigger. But if we are to weather the ecological upheavals now bearing down upon us, the insights expressed by the writers in this book will need to become mainstream, no longer a dissident creed but a dominant one reflected in all our literature. Wildness will always be essential—but not sufficient.

LOA: Anyone thumbing through the book has to be struck by the substantial number of contributions by women, from Lydia Huntley Sigourney and Susan Fenimore Cooper through Mary Austin and Rachel Carson to Annie Dillard, Terry Tempest Williams and Barbara Kingsolver, among many others. The environmental movement even spawned eco-feminism. Was it an accident of history that the environmental movement happened just as feminism was emerging as a political force or are the two inextricably entwined?

McKibben: Good question, and I don’t know the answer. Women seem to me to have broadened the areas of concern of environmentalism some, often being less concerned with the wilderness hero model of being.

LOA: Is there some special quality that distinguishes American environmental writing?

McKibben: Other cultures are older and perhaps therefore more subtle in their observation of the endlessly fascinating dance of human beings. Only on this continent was Culture fully conscious while Economy went about the business of knocking down Nature. The ancient world, Europe, Asia—these underwent huge ecological changes before anyone was writing books. But the kind of disastrous deforestation that the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh only hints at, Aldo Leopold watched happen. Only here did that witness take place in a context of general affluence that made vigorous questioning possible—more and more of us were freed from the need to directly subdue the natural world in order to secure our dinner. We had more room for thinking. As a result, this is a literature with measurable effects. The body of writing anthologized here drove the political side of the movement more often than the other way around. Marsh and Muir gave us national parks, and Robert Marshall and Howard Zahniser the Wilderness Act.

LOA: Creating American Earth must have involved considerable digging, ingesting, savoring, pruning—any final thoughts on what you’ve created?

McKibben: I’d always thought that this was an incredibly rich and wonderful stream of American letters. Now I think I’ve helped prove it.