The haunted house is never just a house—rather, the phantasmagoric happenings within its walls tend so often to blur into the tormented inner lives of its inhabitants, to the point where commonly accepted divisions between psychology, magic, and the material world dissolve altogether.

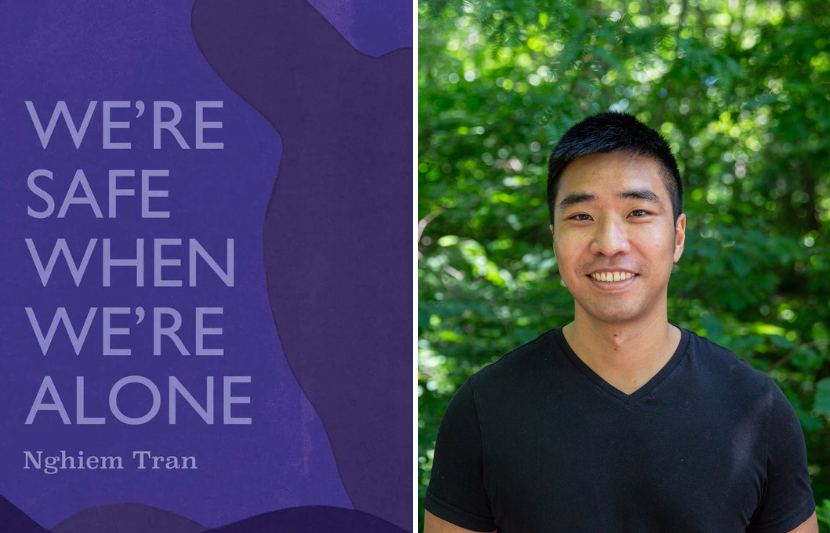

Such is the human-scale horror explored by Nghiem Tran in his debut novella, We’re Safe When We’re Alone, out this September from Coffee House Press. Centered on Son, who’s lived his entire life inside a mansion while engaged in solitary pursuits and watching ghosts work the farms outside, the book performs a hypnotizing act of ventriloquism, speaking profound truths about identity, loss, and assimilation through the magic mirror of genre.

“Nghiem Tran’s first novella is a marvel: a moving, lyrical piece of prose that happens to be an unputdownable page-turner,” writes Mary Karr. “He has created a magical world—in the mode of Gabriel García Márquez or Maxine Hong Kingston—that’s astonishingly real. Read it and feel yourself transformed, maybe even saved.”

Below, Tran discusses his debt to the godmother of phantasmal fiction, Shirley Jackson, and how the poetry of Louis Glück helped shape the voice of his nightmare-beset narrator.

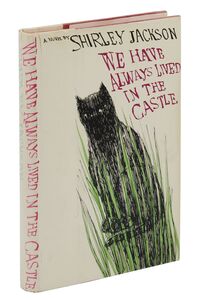

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

I wrote We’re Safe When We’re Alone immediately after I finished Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. At the end of the novel, the narrator shuts herself in the castle and states, “We are so happy,” despite the grim circumstances of her life.

The narrator’s insistence that isolation is the optimal way for her to live thrilled me, and an image appeared in my mind of a boy running through a hallway in fear of some invisible force trying to break down the walls. I asked myself what he was afraid of, and the main answer I could think of was that he was the only human in a purgatory world full of ghosts. If he stayed inside the mansion with his father, then he would live a happy life. But if he left, then the ghosts would consume his soul.

It was freeing for me to read about characters who unabashedly chose to be alone instead of changing themselves for their community.

In other stories, once a character entered a haunted house, their identity deteriorated as they lost their grip on reality. But in my story, I wanted the narrator’s identity to strengthen as he clung to his life in the mansion. Jackson’s use of the haunted house to liberate her characters by isolating them from the rest of the town inspired me to craft a narrator who adamantly fought for the serenity of solitude over assimilating into a society that he would never belong to.

As I wrote the novella, I realized that I had such a strong emotional reaction to Jackson’s novel because of my experiences as an immigrant growing up in Kansas. As a child, I was constantly told that I had to assimilate in order to survive in America. Of course, this turned out to be true, and I was able to excel in school and gain a comfortable life, but at the same time I became tired of forcing myself to belong to communities I wasn’t interested in.

And so it was freeing for me to read about characters who unabashedly chose to be alone instead of changing themselves for their community. This tension between isolation and assimilation became the core element of the novella, with the haunted house as the primary defense for the narrator’s identity.

Poems 1962–2012 by Louise Glück

To craft the narrator’s voice, I turned to the poetry of Louise Glück. Due to the setting of the afterworld, I wanted the voice to feel grand and mythic. One aspect of the narrator’s personality is his hatred of the rural landscape surrounding the mansion. As I reflected on his attachment to the mansion and his hatred of the world of the ghosts, these lines from Glück’s “The Sensual World” came to me:

I caution you as I was never cautioned:you will never let go, you will never be satiated.

You will be damaged and scarred, you will continue to hunger.Your body will age, you will continue to need.

You will want the earth, then more of the earth––

Sublime, indifferent, it is present, it will not respond.

It is encompassing, it will not minister.Meaning, it will feed you, it will ravish you,

it will not keep you alive.

The severity of these short statements frightened me when I first read them. The speaker’s certainty that nothing on earth can ever satisfy an individual’s desires spoke to the restlessness that had plagued me all my life.

In other poems, especially the ones in The Wild Iris, Glück turns the natural world unfamiliar and mythic by having flowers speak about their disdain for the drama of human relationships or about their sorrow over their imminent mortality. I gave my narrator this same kind of authority as he speaks about the society outside of the mansion. He believes it is a place where the ghosts will fill him with endless maddening desires, justifying his wish to isolate himself for eternity.

Nghiem Tran was born in Vietnam and raised in Kansas. A Kundiman Fellow, he received his BA from Vassar College and his MFA from Syracuse University. His debut novella, We’re Safe When We’re Alone, will be published this month by Coffee House Press.