The following remarks were given by Maxine Hong Kingston at LOA’s 40th anniversary gala reception on May 1, 2023. For more on the event, including videos, photos, and transcripts of featured speeches, click here.

I discovered Thoreau when I was a kid, and I say I discovered him because this was not a school assignment. I found him for myself. This was at a time when I read for how-to—how to do anything—and to this day, the genre of how-to books is one of my favorites. I loved Walden, and wanted to live and write like Thoreau.

From Walden, I learned that it’s OK to live on as little money as possible. I learned that it was OK to dress in homemade clothes. And I learned that it’s good to raise our own food in our backyard. My earliest, happiest memory was watching the snow peas grow, loving their shades of purple, violet, lavender, and pink. I’m Thoreau with the beans.

When I got older, I wanted to build my own little house—Thoreau called his a box. I wanted a box. The first box was a shed in our backyard. We kids took out all the junk, and I put in curtains and furniture. And so that became my box.

Then I was thinking: what did Thoreau do in his box? I don’t think that was in Walden. It must be that he was writing in there, because that’s what I wanted to do when I got into my box. The next box I made, I went into the house, emptied the pantry—we had a walk-in pantry—got a typewriter, a table, a chair, and there I started writing novels and stories.

After the Oakland Hills Fire of 1991, instead of a garage, we built a. . . I didn’t know what to call it. Mostly I was calling it an “office.” And then my friends, my artist friends, were calling theirs a “studio,” so I tried to call mine a studio. But that didn’t work, and a box doesn’t work. So, since I live in California: casita. I have a casita and it is just the same size as Thoreau’s box.

When I grew older and looked for work, I had to find meaningful work. I cannot do any job that has a wrong, unethical product. And the job that I found that is meaningful is teaching school and being a teacher. Most of my working life has been teaching high school.

Thoreau said that he loved a broad margin to his life. And I could think of that to mean many things: that he wanted to be far away from other people; he wanted to find solitude; he wanted to be in the woods and not the city. But he never could get away. He could not get away from human problems. Even in the woods, he could hear military, martial music coming from Concord. And what he said was, “My fellow citizens are rallying for war against little Mexico.” That’s why he refused to pay his taxes—that tax was for war against Mexico. We know now that that war with Mexico reverberates to this day, and we are living the consequences.

Now I understand when Thoreau says he wants a broad margin to his life—margin, margin, that’s another word for border. Thoreau going to jail for not paying his taxes gave me strength when I myself went to jail to protest Shock and Awe against Iraq.

Thoreau taught me to be and to live in the real, actual, solid, physical, natural world. But Emerson taught me and affirmed my life in the mystical, the supernatural, the spiritual world, the soul world.

I was older when I read Emerson. I had read the small essays, “The Over-Soul” and “Self-Reliance.” I was so impressed by them, those two essays and also by Walden, that I registered for school at Berkeley that my religion was Transcendentalism.

I only read the selected Emerson a few years ago because Toni Morrison sent it to me after the big fire in California, the big one in Oakland and Berkeley, burned my neighborhood, the forest, our house. It burned the writing I was doing, it burned my library—I think we had like 5,000 books or so. And Toni Morrison sent me the collected Emerson.

Emerson wrote about actual communion with God in oneself. He wrote about having direct experience—that’s his word—of the spiritual and the mystical. He wrote about the universal mind. And as I was reading, I thought, “Wait a minute, this is the Dalai Lama. He sounds just like the Dalai Lama.” The words, the translation from the Tibetan. Wow!

Earlier in learning about the Transcendentalists, there was such an emphasis on self-reliance. That’s why we Americans are such individualists. But I don’t think that was what Emerson was talking about, that we should be individuals. Rather, I think he was saying that we don’t need an intermediary between us and God. We can have a direct experience with a universal mind on our own. That’s just like the Dalai Lama, that we can individually reach satori.

Another way he was like the Dalai Lama: Emerson talked a lot about form and how form can appear and disappear. This is like the Heart Sutra, where there is no form, there is emptiness. Emerson said that there is a God that’s within us. He called it “one man with a capital O and a capital M.” He says that we are all connected to all. We are one. There isn’t just me, there’s all. And this is exactly what the Dalai Lama says. We are one.

Thoreau taught me to be and to live in the real, actual, solid, physical, natural world. He also gave me the title for my long poem, “I Love a Broad Margin to My Life.” But Emerson taught me and affirmed my life in the mystical, the supernatural, the spiritual world, the soul world. He used that word “soul” again and again, sometimes with a capital S and sometimes with a small S. Emerson taught me soul, and that I have one, and we have one, and we are the universal soul.

Yesterday, my husband Earll and I went to the Morgan Library and saw a letter that Thoreau wrote to Emerson. You can tell by Thoreau’s handwriting that he wrote fast. His feather pen flew. He wrote lightly and spontaneously. It’s not easy to make out what he’s saying. Some words were linked together (like Hawaiian when first written). Language flowed.

The letter starts off, “Dear Friend”—it doesn’t say “Dear Ralph”; it’s “Dear Friend”—“I am stealing this stationery to write you a letter.” Well, that is so Thoreau. He doesn’t own things; he depends on friends to give him stationery, and food, and land. He thanks Emerson for a dinner party the night before. How much fun it is to play with Emerson’s fifteen-month-old daughter. (This truly touched me because I’m a grandmother now.) Edith is sitting on Emerson’s shoulders. She talks but can’t pronounce things correctly; Thoreau writes down how she pronounces baby words. And he wonders at the world from her point of view. Edith “studies the heights and depths of nature. On shoulders whirled in some eccentric orbit.” How fascinating that Thoreau saw Emerson as eccentric.

There are some things that Thoreau and Emerson did not write about that were important to their lives. They had a commune, a sangha, that made their way of life transcendent. Bronson Alcott put that commune together, but it was his daughter, Louisa May, who wrote about it best. I like to think of her as another one of the kids who was at their dinner parties. She wrote about communal living in Little Men, and also in the Rose in Bloom series. And in Work: A Story of Experience, she wrote about working in a factory. Realistically, she helped support these men and their ideals.

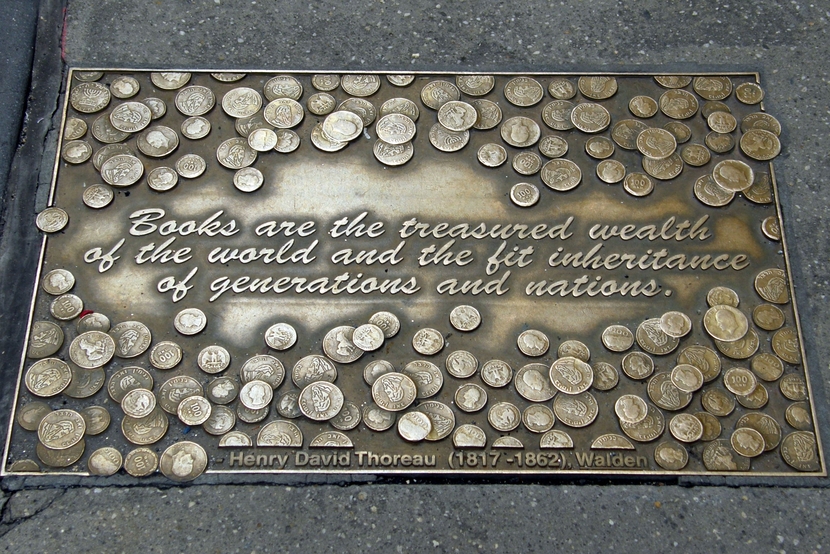

Yesterday we walked Library Way, in front of the New York Public Library. Here’s Thoreau’s words engraved in bronze: “Books are the treasured wealth of the world and the fit inheritance of generations and nations.”

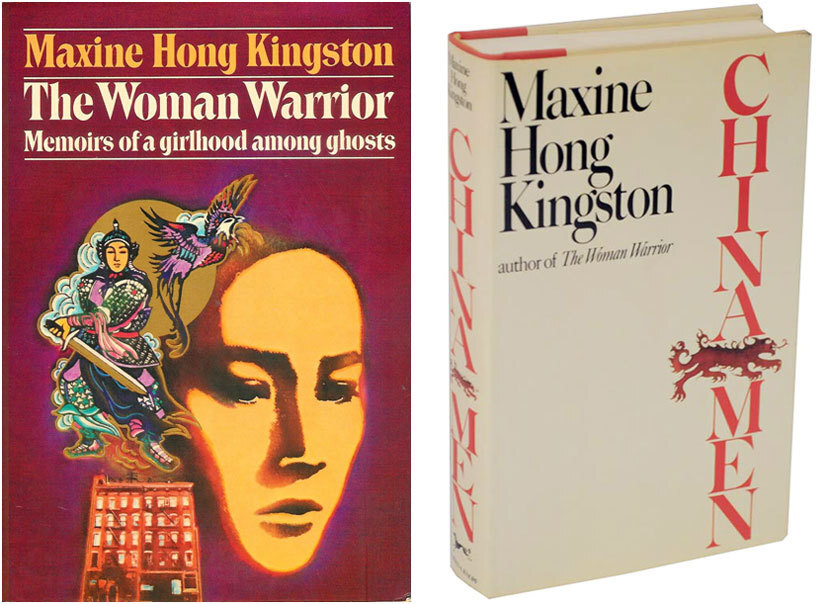

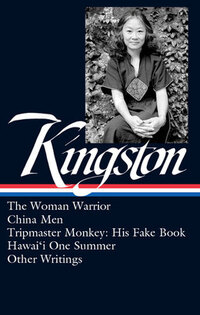

Maxine Hong Kingston transformed American autobiography and family memoir beginning with her 1976 debut, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts. Along the way, she claimed Asian American history and experience for American literature, opening a path for the many writers who have followed her. Hua Hsu wrote in The New Yorker: “The Woman Warrior changed American culture.” A Library of America volume devoted to Kingston’s writing, edited by Viet Thanh Nguyen, was released last year. With its publication, she becomes one of only four living writers in the LOA series.