The following remarks were given by Adam Gopnik at LOA’s 40th anniversary gala reception on May 1, 2023. For more on the event, including videos, photos, and transcripts of featured speeches, click here.

Library of America, among the countless other things it has done, brings together two of my peculiar citizenships. One is citizenship in The New Yorker magazine, where I have worked and written for the past forty years, and the other is adopted citizenship in the country of France and particularly in Paris.

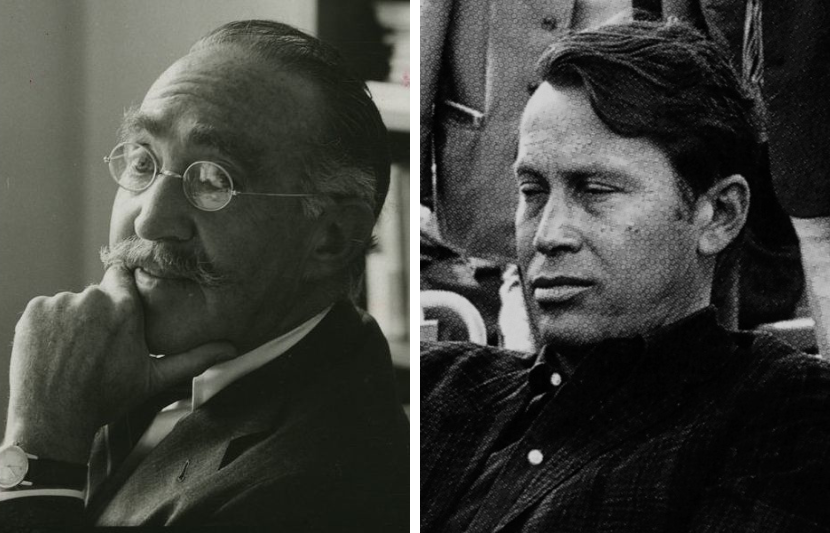

Those two things may seem somewhat far-removed, but as is worth remembering anytime we celebrate Library of America, that began as a dream in the head and mind of one of my greatest predecessors at The New Yorker, the critic and essayist Edmund Wilson. And it began as a dream in the mind and imagination of Edmund Wilson exactly because Edmund Wilson was simultaneously a great patriot of American letters and an instinctive cosmopolitan, deeply in love with French civilization.

He had realized that in France, the Pléiade series—which had begun then and continues on to this day—had done something that had never been done for American literature, and that was to create a series of uniform volumes, uniformly edited, uniformly issued, that would get all that was essential to French literature in an easily and readily available edition.

Wilson wrote at length, and often, about the need for the same thing to happen in America, for someone to produce an American Pléiade. So, it was exactly his cosmopolitan knowledge of what had been possible and necessary in French literature that fed his powerful sense of American literary patriotism. Because what we tend to forget too easily is the degree to which Wilson’s generation had to make the fight for American literature as a primary literature—not as a secondary or derivative literature, but as a literature that could stand on its own alongside English literature or French literature or the literature of any other language.

That was the brew, the primordial soup, in which the vision of American literature that the Library of America exemplifies began, exactly in the mixture of an inspiration from France and an enormously patriotic impulse of a powerful and salubrious kind here.

We take that for granted now, but we forget the act of moral heroism that was required for Wilson’s generation (Wilson himself, but forgotten figures like Van Wyck Brooks as well) to put the case that not only had the American literature of the twentieth century—the literature of Hemingway and Faulkner, which had come to dominate center stage—utterly changed the world, but so had the literature that preceded it, the writing of Twain, Dickinson, and above all Herman Melville.

(I found out only very recently, in terms of making these constellation-like connections, that the great French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville, who was originally named nothing like Melville, had taken Melville’s name at the height of the Nazi occupation of France as a sign of his commitment to our Melville’s existential vision.)

That was the brew, the primordial soup, in which the vision of American literature that the Library of America exemplifies began, exactly in the mixture of an inspiration from France and an enormously patriotic impulse of a powerful and salubrious kind here. It informs the work of the Library of America, I believe, right to the present moment.

Let me speak quickly about the three volumes I’ve been engaged with in the past couple of years. They are, by the original standards of Wilson’s vision, somewhat eccentric.

One was the collected works of S. J. Perelman, certainly a humorist and satirist of the first rank whom Wilson keenly admired. Wilson once said of Perelman that Sid was the only writer at The New Yorker who somehow escaped the dead hand of the copyeditor, and that he didn’t know how he did it—words which I have emblazoned above my desk in my perpetual struggles to do the same. (His precise words were, “The object here is as far as possible to iron all the writing out so that there will be nothing vivid or startling or original or personal in it. Sid Perelman is almost the sole exception, and I have never understood how he got by.”)

But really, Perelman was not the kind of writer whom Wilson and his coevals had in mind when they began Library of America. They were thinking of Melville and Twain. They were thinking of Howells and Dickinson. They weren’t thinking of the man who wrote the best Marx Brothers movies, Perelman. And yet Perelman’s work as a satirist fits and slots perfectly into the ever-expanding sense of what the canon is that the Library of America is devoted to exploring.

This expansion of the canon is an ongoing act of pluralism: we have brought in science fiction, and noir novelists of a kind who were taken as dismissible pulp fiction in their day and never would have seemed headed for an American Pléiade. But here they are, and everyone is grateful for their presence, shining in the night sky. A too-hasty pluralism confuses values and categories and thinks that what has been ruled in must be ruled out; a wise kind knows that literary values escape categories, and that great writing emerges as often in marginalized places as in central ones, but that the literary criterion, delight in language and intensity of imagination, is the same all over the Library.

The other two volumes were of a seventeenth-century playwright working in an absolutist court—Molière—as translated by a major American poet in the 1940s and ’50s, Richard Wilbur. Once again, that was a volume that I think would have fallen outside of Wilson’s purview, his sense of what a Library of America ought to do.

But what Perelman and Wilbur have in common is that they are both great readers. Perelman’s work, as I tried to explain in the introduction I wrote for our anthology, is above all a record of reading, the record of a Jewish kid growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, who read everything—French, English, Italian—and created an entire fantasy world for himself out of everything he had read, which he then offered to us in revised and constantly amended and beautifully baroque and distended form throughout his life.

Wilbur was a GI who came upon European culture at the moment of its absolute crisis, when it seemed to be breaking apart at the end of the Second World War. And like so many of that heroic GI generation of writers, he decided that he had to preserve and literally translate some part of it to bring to America at a moment of our cultural ascension.

So, he went about the task of translating Molière into rhyme, which, believe it or not, had never previously been attempted by any English-speaking translator. Molière’s plays are written in rhyme, of course, but no one had seen the necessity of it. It was a genuinely heroic act, and as I tried to explain in an essay in The New Yorker not long ago, Wilbur’s infatuation with rhyme and his desire to make Molière’s particular kind of comedy of manners newly accessible to American audiences in the ’40s and ’50s was not, in any sense, an academic exercise. Rather, it helped create and seed the great renaissance of American rhyming verse which continues to delight us in everything from the work of Phyllis McGinley to the great masterpieces of our much-missed Stephen Sondheim.

Both Perelman and Wilbur are readers who become writers, and for those of us who are also reader-writers, they are enormously cheering. But they also persist and exist for us as examples of how the cosmopolitan spirit feeds genuine American patriotism, of how a love and a relish for cultures and languages outside our own feeds and enriches our love for everything that is indigenous and native to these shores and to our language.

We live in a moment of seemingly unending political crisis in which a new form of nationalism threatens all of the humane and liberal values that we inherit from Wilson, from Wilbur, from Perelman, and from the entirety of Library of America.

The antidote for that kind of nationalism is not indifference to the nation. It is exactly the kind of patriotism that is always and necessarily transitive with cosmopolitanism. That is why there’s nothing in my life that makes me prouder than being involved with the Library of America.

After joining The New Yorker in 1986 as art critic, Adam Gopnik has gone on to write brilliantly about—everything. Whatever he’s explaining—cities or food or literature or politics or painting or clothes or the million other things he has paid attention to—he is one of the most insightful, most astute, and most elegant writers we have. In addition to his acclaimed essays and books, he has turned his hand to children’s fantasy literature, a musical, and this past year, an acting role in the Oscar-nominated film Tár. A Library of America Trustee since 2016, he has edited series volumes devoted to S. J. Perelman and Richard Wilbur’s translations of Molière, as well as a collection of American writers on Paris.