Charles Brockden Brown may not have been the first American novelist, as some have claimed, but in the course of his “frantic, doomed career” (to quote the critic Leslie Fiedler), he effectively shaped the enduring myth of the American writer. In his 1960 classic Love and Death in the American Novel, Fiedler quotes one of Brown’s contemporaries describing the artist at work:

Passing a window one day I was caught by the sight of a man, with remarkable physiognomy, writing at a table in a dark room. The sun shone directly upon his head. I shall never forget it. The dead leaves were falling then. It was Charles Brockden Brown.

The Romantic fancy, the foreboding shadows, the at once touched and tortured individual absorbed in the act of creation—each detail contributes to a still-recognizable portrait of the literary genius beset by storms of mind and spirit. Dead from tuberculosis by the age of thirty-nine, Brown, says Fielder, “determined, through his influence on Poe and Hawthorne, the future of the gothic novel in America.”

A Library of America edition of Brown’s writings gathers three of his macabre novels, including Wieland; or The Transformation, perhaps his best-known work, a terrifying tale of murder, religious fanaticism, guilt, and deception set in rural Pennsylvania.

Though Wieland is not as widely read today as many of the works it influenced, an upcoming film adaptation hopes to draw a wider audience into Brown’s haunted company. And adding to the intrigue, it’s a musical—certainly not the first genre that comes to mind when thinking of the writer’s particular brand of madness and bloodshed.

Speaking with LOA via email, director Cody Knotts shares his personal connection to Wieland, the challenges of converting eighteenth-century dialogue to the sensibilities of twenty-first century viewers, and his plans for building out a rich cinematic universe based on American Gothic literature.

LOA: Charles Brockden Brown is frequently called America’s first professional novelist, and Wieland the first American Gothic novel. What originally drew you to this underrecognized literary originator and his 1798 masterpiece?

Cody Knotts: The moment I read Wieland, I felt a kinship with the milieu of the novel. I was raised in a deeply religious world more in touch with the nineteenth century than the twentieth or twenty-first. My grandfather founded an evangelical church in Pennsylvania and Wieland’s historical background material—the thread connecting the Camisards, Hussites, and Shakers—leads to my experiences in those brush arbor churches.

This was not the Joel Osteen brand of Christianity, but a deeply mystical world. Wieland, unlike most texts touching on the spiritual life of early America, depicts a culture that is fundamentally spiritual and yet simultaneously deeply sexual, passionate, and wild. It was a world largely forgiving of sins of passion, in stark contrast to the more puritanical world of New England.

“Flesh out, repent later,” was a common refrain in my childhood, and I vividly experienced the conflict between morality and sexuality. The character Theodore Wieland is unable to find equilibrium in the war between desire and virtue. To me, Wieland shares central themes with one of my favorite films, American Beauty, but within the framework of early American religious fervor.

Finally, literature provides a conveyance to journey into the minds of our forebears, a window into the world as they perceived it. I find there is no more perfect vehicle to understand early America than Wieland.

LOA: Wieland touches on a number of macabre themes—murder, madness, suicide, and religious fanaticism—yet the film takes the form of a musical. Why did you choose this creative approach, and how did you go about setting Brown’s terrifying tale to song?

Knotts: So much of Brown’s novel takes place within Clara’s mind and—by her own admission—she is an unreliable narrator. We used music to suspend the perception of reality within the film and to enter into Clara’s thoughts, passions, and desires. In the novel, the main characters are highly musical in spite of their isolation. Even Brown’s decision to name his characters Wieland and Pleyel evokes musical associations: Christoph Martin Wieland (1733–1813) was a German playwright and operatic librettist, while the Pleyel family were noted composers and piano manufacturers.

One of the mistakes of modern society is that we view people of the past as less rational and more superstitious than ourselves, but a desire to demystify the inexplicable is a universal aspect of human experience.

We made a conscious choice to only use music from the time period in which the film was set (the American Civil War rather than the French and Indian War of the novel). Works by Chopin and Stephen Foster became centerpieces of the film—Chopin because of his relationship with the Pleyel family and Foster because he represents the quintessential American musician, a man who dedicated his enormous talents to entertaining the masses. In both cases, their brief lives and enduring music were tinted by the specter of death. Life in that era, even for the wealthy, was likely to be “nasty, brutish, and short,” to quote Hobbes.

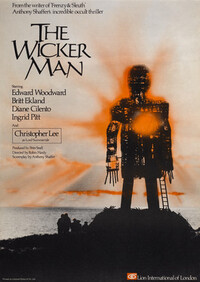

We also incorporated some marvelous period murder ballads, including some of the British ballads collected by pioneering nineteenth-century musicologist Francis James Child. The 1973 film The Wicker Man was our model for the film as a musical; the songs help to evoke the folk-horror ambiance. It is not a through-composed pseudo-opera like Sweeney Todd. Rather, the music accentuates the sensate world of the tale.

LOA: Published in the late eighteenth century, Wieland proved widely influential in its time, inspiring authors including Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Shelley, and George Lippard. Yet compared to those writers’ work, Wieland is fairly obscure today. Why resuscitate Brown’s novel for contemporary audiences in 2023?

Knotts: Wieland speaks to deception of the senses, which is a timely theme thanks to modern technology. What can we trust in our environment? Almost everything we hear, read, or see could have been manipulated or manufactured through artificial intelligence.

One of the mistakes of modern society is that we view people of the past as less rational and more superstitious than ourselves, but a desire to demystify the inexplicable is a universal aspect of human experience. Brown wrote Wieland at a time when science and religion vied to provide explanation for seemingly incomprehensible phenomena, and this is a chief theme of the novel. In the film, Carwin asserts that “belief’s sole purpose is to explain the unknown.”

Wieland is the perfect vehicle for exploring the conflict between science and religion. In fact, I believe it is this conflict that inspired Mary Shelley’s treatment of the potential madness of science in Frankenstein. Brown explored the madness of religion, she of science. All of this inspired our tagline for the film—“There is a thin line between righteousness and madness”—which I believe is especially relevant in our current world of extremes.

LOA: Your past films have included the conspiracy thriller Kecksburg and Pro Wrestlers vs. Zombies, stories with some connection to Wieland’s dark subject matter but still quite different in terms of genre and setting. How does Wieland fit into your filmmaking career? In what ways is it a continuation or departure from your past work?

Knotts: Film was always my secret love and passion, but I grew up in rural poverty. As a boy, I did not dare to imagine that I could bring a story to life on the screen. Instead, I became a newspaper editor, channeling my creative energies into reporting on local politics. That effort nearly destroyed me. I fought for four years against a corrupt district attorney and helped free three men wrongly accused of murder, but my involvement with this investigation destroyed my marriage and left me emotionally and spiritually bankrupt.

Through prayer, I was guided to pursue my true passion for filmmaking, but I initially chased notoriety through films that were rooted in sensationalism and pop culture. I made a ton of mistakes and some not very well-made films, but my dream was always to make films that had enduring value, that would state something about the human condition.

The conflict between rationalism and belief in the supernatural, between perception and reality, is as relevant today as it was more than 200 years ago, and that universality puts Brown in the first rank of early American writers.

I believe that the most underdiscussed aspect of life is desire. Desire is what drives our actions and is the key to our “secret” selves. My favorite film, L.A. Confidential, has the same undercurrent of repressed desire that I recognized in Wieland. This is the first film I’ve made which represents my true goal: to create films that speak to the reality of the human condition.

LOA: In the course of creating the film, did you discover any new or unexpected appreciation for the Wieland novel or Brown as a writer? How did adapting the book deepen or change your relationship to the work?

Knotts: I have spent two years of my life with this novel and it has become part of my very existence. It is the greatest honor to breathe cinematic life into Brown’s words. He understood the madness that fanatically held beliefs can create. Although he was inspired by the Yates murders in upstate New York, his decision to shift the murder from an undereducated farmer to a highly literate, cultured, and yet isolated society was quite a transformation. The conflict between rationalism and belief in the supernatural, between perception and reality, is as relevant today as it was more than 200 years ago, and that universality puts Brown in the first rank of early American writers. The novel is highly atmospheric; translating those words into the visual world of film was both a challenge and a delight.

LOA: What were some of the challenges you encountered transforming Brown’s novel into a film musical? Were there elements of the novel that proved especially difficult to translate, or scenes you had to get extra creative to pull off?

Knotts: The biggest problem was Brown’s somewhat archaic language, which sounds unrelatable to a modern audience. We wanted the characters’ words to reflect their social class and their high-minded belief system influenced by the King James Bible, but it had to be intelligible to a wider audience. We decided to use the original unaltered dialogue only when Wieland is consumed by his religious madness.

This idea was inspired by the use of language in Brian Hegeland and Curtis Hansen’s L.A. Confidential, where only Danny DeVito’s character speaks in the slang of the 1950s. None of the other characters use archaic personal pronouns such as “thee” and “thou.” Even where the original dialogue was retained verbatim, we had to judiciously shorten Theodore Wieland’s long monologues. The speaking style of the other characters had to reflect their erudition and, frankly, the education of the audience. In scenes for which Brown did not provide dialogue, we had to create conversations in keeping with the characters’ established voices.

In particular, Clara had to sound elegant, intellectual, and cunning. Among the lines we created for her are:

“No, that is lust, the flame that burns twice as bright and half as long.”

And:

“If there was no desire, there would be no virtue in the renunciation of it.”

One of my favorite new lines was Theodore Wieland saying, “Why do you bruise a heart that beats so fondly for you?” Our goal was to make a film that sounded a bit like Shakespeare transplanted to early America—which I believe was Brown’s goal—and to honor him and the entire American literary experience that he inspired.

Another problem was how to handle the relationship of Clara and Theodore with their parents. The novel spends a great deal of time on the father’s journey and his efforts as a missionary. In the film, we focused on the childhood events that would most influence Clara and Theodore Wieland in later life. The initial six minutes of the film had to condense the first two chapters of the novel—the madness of the parents’ religion, the children’s love for them, the father’s mysterious death, and their childhood relationship with Pleyel and Catherine.

The final major challenge was the relationship of Pleyel and Clara. Pleyel is not the most interesting character in the novel, but from the perspective of Clara, he is the whole world. Once we made the decision that everything in the film (as in the novel) was from the perspective of Clara, then we could mold Pleyel as her vision of him. Like Scarlett’s perception of Ashley in Gone with the Wind, Pleyel represents Clara’s vision of perfection, not a flesh-and-blood human being.

LOA: You’ve envisioned Wieland as the first in a series of films inspired by eighteenth-century Gothic novels. Can you talk a little more about this broader project and the thinking behind it?

Knotts: History, mystery, and memory are the hallmarks of all great stories. The greatest and most enduring films are almost entirely derived from great works of fiction: The Godfather, Gone with the Wind, and Doctor Zhivago. Their heroes and heroines were very human, deeply flawed, and their personal struggles occur within the panorama of historical events.

More recently, the film marketplace has largely focused on science fiction, children’s novels, or superheroes. I’m a realist: the marketplace for so-called “prestige films” (in other words, complex yet universal stories) is about $40 million worldwide, according to Roy Price, founder of Amazon Studios. That means the cost of production for these types of films must come down.

In the past, films based on Gothic literature were created by American International Pictures and Hammer Studios. They were made on relatively limited budgets but with an emphasis on production values. Inspired by this model, our production company will lower costs by focusing on a specific genre and time period. We also created museum-quality historical reproduction clothing for Wieland for far less than the industry standard because of our knowledge and expertise.

Part of our plan is to create cinematic adaptations of stories like those contained in the Library of America’s American Fantastic Tales volume edited by the late Peter Straub. These stories will always be part of the American literary canon and they deserve to be brought to life for new audiences in the twenty-first century and beyond.

We are currently seeking partners worldwide to bring ten literary works, none of which have previously been cinematically adapted, to the screen over the next five years for a total budget of $10 million. This model was created by Roger Corman and we believe it can not only be successfully duplicated but also enhanced. Consider the success of recent films such as The Witch or Midsommar, which blended elements of Gothic literature and folk horror. Now consider the potential impact of films which emulate aspects of those successes while also bringing to life time-honored stories which are part of our cultural legacy. Our adaptation of Wieland is the first step toward that goal.

Cody Knotts is a director, producer, writer, and actor. A native of Taylorstown, Pennsylvania, Knotts previously served as the editor of the Weekly Recorder, a newspaper covering Pennsylvania and national politics. His past films include Kecksburg and Pro Wresters vs. Zombies.