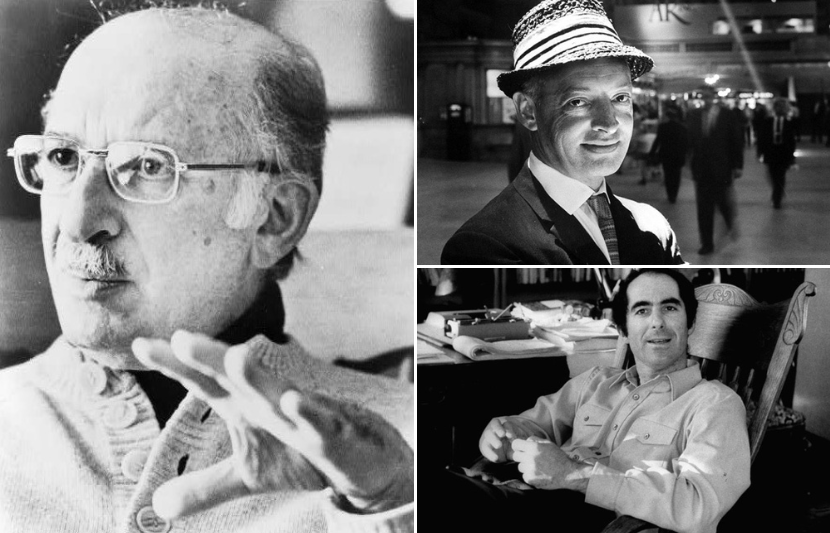

Across eight novels and dozens of stories, Bernard Malamud transmuted tales of poverty and aspiration, love and vulnerability, identity and assimilation into distinctly American myths, suffused with painful humor and a deep emotional seriousness. “The voice was unlike any other,” writes the author Cynthia Ozick of his work, “haunted by whispers of Hawthorne, Babel, Isak Dinesen, even Poe, and at the same time uniquely possessed: a fingerprint of fire and ash.”

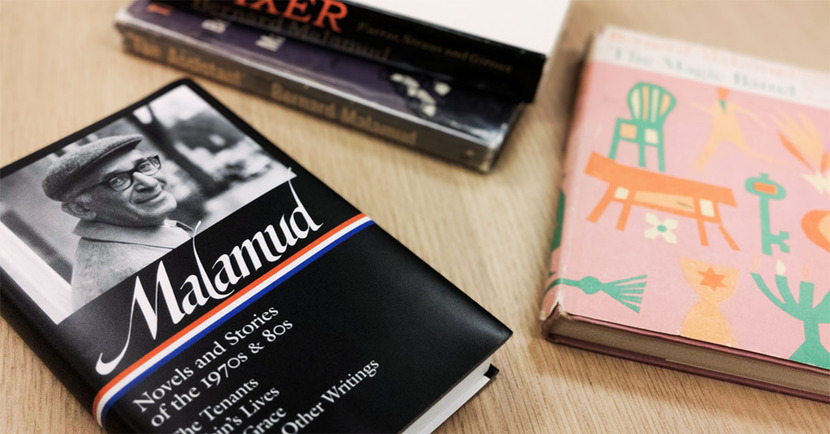

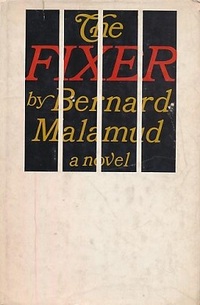

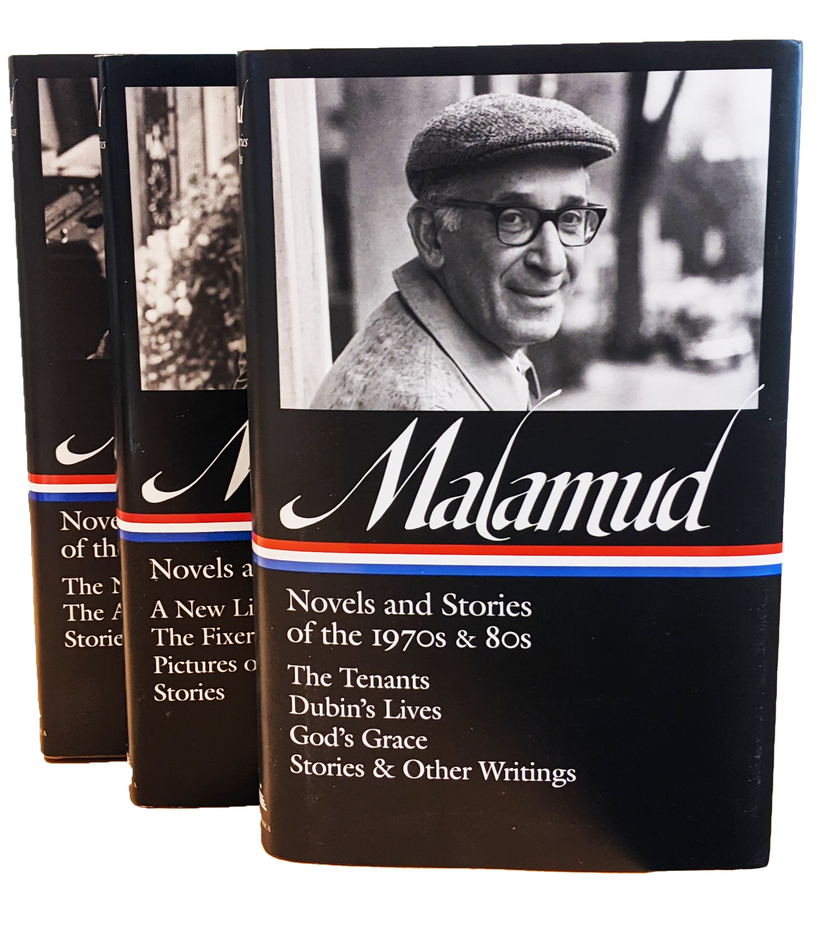

In the three-volume Library of America edition of Malamud’s fiction, edited by Philip Davis, readers will encounter a dazzlingly original writer of the highest order. From early triumphs like the classic baseball novel The Natural and the revelatory story collection The Magic Barrel to career milestones such as the Pulitzer Prize– and National Book Award–winning The Fixer, Malamud carved out a singular space in American letters, suspended somewhere between the decrepit tenements of Jewish immigrant New York, the rarified worlds of academia and literature, and the unquantifiable, irrational realm of the mystic and the supernatural.

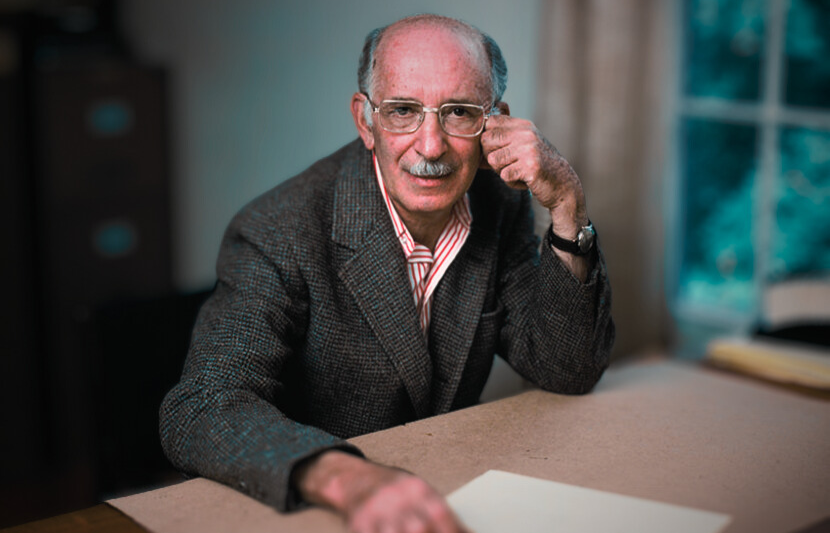

Via email, Davis spoke to LOA about Malamud’s remarkable trajectory and legacy, including his relationships to peer-rivals Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, the strains of autobiography that run through his novels, and what his masterful revisions reveal about his creative evolution.

LOA: Malamud is often grouped with Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, two authors who admired him and cited his influence, as a “Jewish writer.” Yet Malamud resisted this categorization, saying in an interview on his 60th birthday, “I’m an American. I’m a Jew, and I write for all men. A novelist has to or he’s built himself a cage.” How did Malamud’s Jewishness find expression in his fiction, and how does he fit into the artistic lineage of midcentury American Jewish writers?

Philip Davis: Saul Bellow ruefully described that trio of himself, Malamud, and Roth as the Hart Schaffner Marx of literature: the Jewish literary equivalent of the first-generation rag trade gone upmarket. But Bellow was born in 1915 and Malamud in 1914, while Roth was the junior partner, born in 1933. These dates made a difference. To Malamud, Bellow was always the more successful and intellectual, glamorous and fêted contemporary.

When I was doing research for my biography of Malamud, I interviewed the publisher Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He told me a biography of Malamud was ridiculous, that there was nothing there, no excitement in the life. “Saul Bellow,” he said, “was filet mignon; Malamud was hamburger.” Malamud would have deeply felt such a slight, confirming his own insecurities. When Bellow won the Nobel Prize in 1976, Malamud wrote in his notebook, “21 October. Bellow gets Nobel Prize. I win $24.25 in poker.” He always feared that he came second, at best; that he had to start from lower down, with less natural talent and confidence.

His America was not the land of ethnicity, of identity politics, but the melting pot of races gathered in kind. That was his founding and determinedly innocent American belief, as the newly educated son of immigrants and survivors. And for Malamud, crucially, that assimilation was like the melting point of literary realism itself, in which nothing and no one is insignificant, in which everything exists in a complex blend.

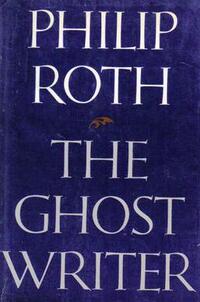

When it came to Roth, this younger writer seemed to Malamud to turn from an admirer in the 1960s to a critic in the ’70s. It was in rebellion against one of his literary fathers that Roth attacked Malamud, characterizing him as too much concerned with Jewish suffering and too attached to a pious, priestlike view of the writerly vocation. When Malamud read this in Roth’s article “Imagining Jews” in the October 1974 issue of The New York Review of Books, he drafted Roth two hurt and bitter letters but only sent him a single sentence: “It’s your problem.” As in: not mine.

Being stuck in a complicated middle position was not a problem for Malamud; rather, it was the place where problems are worked upon. Malamud never wanted to be Isaac Bashevis Singer, a traditional Jewish writer. He wrote in English, not Yiddish, and sometimes in his own blend of the two, “Yinglish” (more on that later). But nor would he leave his Judaism behind—not that he was Orthodox or highly educated in the religion.

What Malamud believed in was assimilation, as an ideal and not merely an acquiescence. His America was not the land of ethnicity, of identity politics, but the melting pot of races gathered in kind. That was his founding and determinedly innocent American belief, as the newly educated son of immigrants and survivors. And for Malamud, crucially, that assimilation was like the melting point of literary realism itself, in which nothing and no one is insignificant, in which everything exists in a complex blend. There are no pure ideas, he told his students, as if in correction of Bellow’s intellectualism.

LOA: Magic and myth live alongside an unvarnished, unglamorous realism in Malamud’s work. What is the role of “magical realism” in Malamud, and how can we interpret the presence of the unreal or surreal in his fiction?

Davis: There is a complicated note that Malamud wrote around the time of Dubin’s Lives that goes like this:

One must transcend the autobiographical detail by inventing it after it is remembered.

I think he loved inventions that convinced him he could indeed be an artist. But those inventions were most powerful when they revealed themselves to him as transmutations of memories and deep emotions, things remembered in a different form and released afresh. Malamud was not an intellectual or conceptualist, so it makes sense that thoughts should come to his characters as experiences. See the young rabbinical student Leo in “The Magic Barrel”:

He gradually realized—with an emptiness that seized him with six hands—that he had called in the broker to find him a bride because he was incapable of doing it himself. This

terrifying insight he had . . . that apart from his parents, he had never loved anyone.

We could indeed talk about magical realism in “The Magic Barrel,” and it is often the short stories that contain Malamud’s zaniest experiments. But all that gives way to what I would call a natural magic in the end: what happens when Malamud’s people surprise themselves, either by risking to love someone, as Leo does, or finding themselves moved by what they hardly knew they had in themselves, like a deep regret or a capacity for unexpected forgiveness. And then the natural magic of Malamud’s prose comes to life. In a world that Malamud found too rationalistic, he would look for any opportunity to force into that cold climate the ostensibly unreasonable, the barely tenable emotional need. So often he writes that a protagonist, at a key moment, does something “for no reason he himself could give.”

LOA: Cynthia Ozick wrote of Malamud, “His stories know suffering, loneliness, lust, confinement, defeat; and even when they are lighter, they tremble with subterranean fragility.” What explains this undercurrent of loss and sadness in Malamud’s fiction, and how does it coexist with the elements of humor and irony so abundant in his work?

Davis: I agree with Malamud’s great editor Robert Giroux, whom I interviewed after meeting his business partner Straus: however much he admired Malamud, however much he appreciated the brief fictional inventions, Giroux believed it was not the zanier short stories that were Malamud’s greatest achievement, but the seriousness of the novels. Giroux loved the way even the humor was tinged with a deeper sorrow, which the humor itself protected. As Malamud put it, “I like my comedy spiced in the wine of sadness.” The short stories, Giroux said, were no more and no less than experimental interludes between the writing of the major novels. And so the irony, the humor, the magic, all these sexier things are less than the seriousness they serve. Because, finally, Malamud stands for heart-work, the nonnegotiable and always unfashionable commitment to utter emotional seriousness.

But is it really all “suffering, loneliness, lust, confinement, defeat”? I want to say that the best of the work is not just about these things. “What about suffering?” an interviewer asked him. “I’m against it,” he remarked wryly, adding, “but when it occurs, why waste the experience?” So his work is about dealing with loneliness, failure, and so on, and making something of them. It’s about second chances in life for strugglers such as Frank in The Assistant and Levin in A New Life.

He loved William James’s formulation that there are some lucky and talented people who are the first-born, thoroughly at home in the world from the get-go. But Malamud and his people are James’s twice-born, who have to make a second life with all the pains and errors of their first. At the end of A New Life, Levin resolves to marry the wife of his college boss, Gerald Gilley, to the ruin of his fledgling academic career. “An older woman than yourself and not dependable, plus two adopted kids. . . .” Gilley taunts him. “Why take that load on yourself?” But this is Levin’s tough risk of a second life, and he answers, in Malamud’s initial draft:

“Because I have to.”

But Malamud, the great reviser, changed it in the published version to:

“Because I can.”

And then made it, in the thrill of morality discovered by a natural magic in unlikely circumstances:

“Because I can, you son of a bitch.”

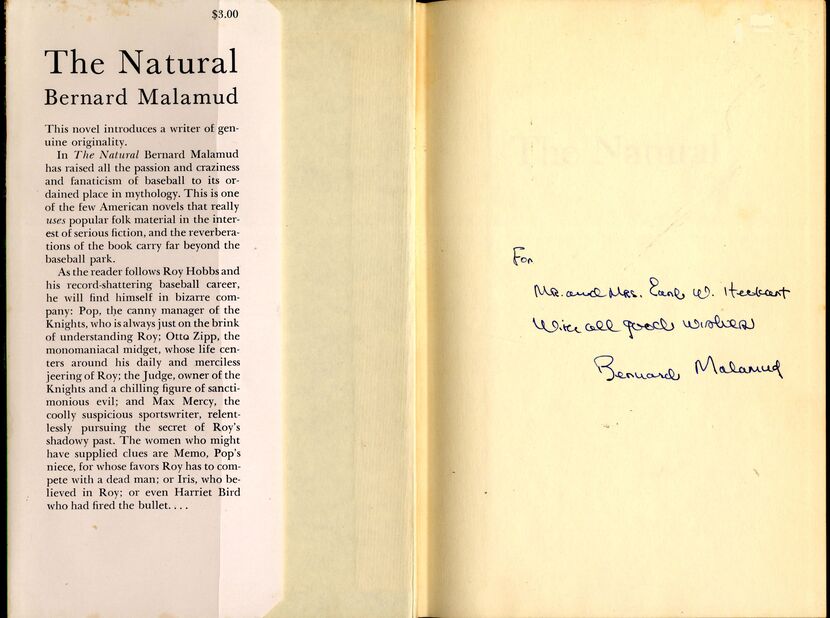

LOA: What is perhaps Malamud’s most famous novel, The Natural, is sometimes seen as an outlier in his career, both for its sports subject matter and its stylistic approach. How can we think about the evolution of Malamud’s writing, from his debut to the critical acclaim that greeted The Magic Barrel and The Fixer to his later works of the ’70s and ’80s? Are there distinct phases of Malamud’s career we can identity to better understand his creative trajectory?

Davis: I love that novel, though it is perhaps most famous because of the half-botched film starring Robert Redford. But there it wonderfully is: sport turned into myth, into ancient combat, and still within the game of baseball this idea of two lives, first Roy Hobbs as a promising young pitcher, then after disaster and a great gap of time, his comeback as a batter. “We have two lives, Roy,” says the woman who stands up for him, “the life we learn with and the life we have after that.”

Malamud’s own second life belongs, accordingly, with The Natural (1952); The Assistant (1957), in part a retelling of his father’s experience with a failing grocery shop; and A New Life (1961), a version of Malamud’s own teaching career in Oregon from 1949 to 1961. Then there was a very rough period in his career between 1969 and 1978, including the interesting attempt to turn short stories into a picaresque novel, Portraits of Fidelman. On either side, there is in 1966 The Fixer, the writing of which nearly killed him despite the book winning the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in the end; and then in 1979 the redeeming, reclaiming triumph of Dubin’s Lives, the heart-wrenching story of a biographer trying to write a life of D. H. Lawrence amid the disorder of his own familial and sexual relationships. These were the novels that he (as he put it) could live within. “If you know Dubin’s Lives,” he told his friend Bert Pogrebin, “you know me.”

LOA: The capstone volume to the LOA Malamud edition includes the previously unpublished autobiographical sketch “A Lost Bar-Mitzvah.” It’s a moving story about a young boy’s growing anxieties about his approaching bar mitzvah, or rather about his parents’ lack of planning for it. How did you become aware of its existence? What does it tell us about Malamud’s troubled childhood?

Davis: Ann Malamud, Malamud’s widow, told me about the “Lost Bar-Mitzvah,” but feared it might be lost. I spent two weeks in Cambridge, Massachusetts, interviewing her for a short period each day, and for the rest of the day looking through papers in her apartment. There I found it, and later I found other versions in the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. It bears out what I said earlier about Malamud not being a formal Jew, Orthodox or learned, but something else that was more emotional and made out of the spirit, not the letter. Finding the little memoir was an intimate and poignant experience.

There among the papers, I also found original letters from Max, Malamud’s father, written to his son in heavy pencil on the brown paper used to wrap goods at the grocery store. Max would write what he considered the important words in capital letters. No one had seen these letters for years.

“Bernie let me know if you Understand my writing if not I will have Somebody to write the letters for Me,” he writes on November 15, 1951, adding, “I Asked Eugene how he spels psychiatrist and he speled that for me. . . . I talk to him like a good father can talk to a child I kiss him and I Bring to him Fruit and Cigarettes.”

Eugene was the younger brother Malamud left behind when he went with Ann to a new life in Oregon. Increasingly, Eugene suffered from the schizophrenia he may have inherited from their mother, Bertha, and had to live in a mental hospital. In Ann’s apartment, and later in Austin, I looked at the long, rambling letters Eugene wrote to his brother and could tell from the handwriting when he was about to take a turn for the worse again. It was a terrible thing that he lived in the same mental hospital where his mother had been sent in 1927 and died in 1929, probably by suicide. In a way, it was also a part of Malamud’s bar mitzvah that he was the one, aged thirteen, who had come home from school to find Bertha on the kitchen floor, having tried to poison herself with disinfectant. Ann told me, “One time his father took him to the mental institution. He did not go in to see her. Now I don’t know whether it wasn’t permitted, or what it was, but his mother came to the window, and they waved to one another and that was the last time he saw his mother.”

But suddenly, when that novel became most straight and serious to me, I thought here is Malamud again, not necessarily known or specific, but what he stood for as a representative of Jewish feeling, itself no more than the representative of something unapologetically and unavoidably emotional in the human heart.

It’s no wonder that Malamud felt that he had had a very hard start, that he was swindled by life itself. But there was an inheritance from Max, finer than the conventional bar mitzvah gifts that the boy resented never receiving. It came via another window, when Malamud was at college, standing outside the old shop:

I remember once having this experience, in walking past his store as he was sitting in it, and I could see all the way through the store, through the little window that had been cut into the wall at the back, and watching him sitting at a table, reading his newspaper, and I felt a strong throb of something for him.

Here we can see “something” of where The Assistant came from. But the most lasting gift was that he heard his father’s voice, its tone and rhythm, every time he wrote in “Yinglish.” In the story “Idiots First,” Mendel, a sick father whose son has an intellectual disability, begs a rich man to help send the boy from New York to family in California before he dies. The rich man’s servant will not let him in the house; “Come back tomorrow,” he says. “Look in my face,” says Mendel, “and tell me if I got time till tomorrow.” And then Malamud adds a single word in revision:

“Look me in my face.”

That’s Yinglish, that’s Max; that is what revision could do, to make the “me” felt.

When Malamud married Ann, a Catholic, Max disowned him—“dead to me” was the phrase—though they were reconciled after the birth of the first grandchild. Later, Malamud discovered that Max always carried with him the letter his son had written him at the time of his decision to marry outside the faith. A man cannot be a real man if he gives up on his love, he had said. Some of this went into “The Magic Barrel,” and then into Dubin’s Lives. So much was redemptive in the writing, pointing to the sheer power of heart in Malamud’s fiction.

LOA: You had already published your biography of Malamud before undertaking work on the LOA Malamud edition. Did your time assembling and contextualizing these materials bring fresh insights into Malamud’s life, or new appreciations of works you thought you knew?

Davis: It was another version of working through the papers in Ann’s apartment, close to the man. I felt privileged, responsible, moved, because I was the first biographer—and often, it seemed, the first person to look through at least some of the files at the Harry Ransom Center and the Library of Congress. I was pained, too, by some of the personal discoveries: it was too soon for there to be an easy, professional distance. And I hadn’t written a biography before, it had just come to me out of loving Malamud’s work.

But here was one surprising thing that arose out of research. Philip Roth had written a version of Malamud in his novel The Ghost Writer (1979). The austere novelist Lonoff was discovered, in that book, to have a secret young lover. Roth believed it was his invention, in exuberant unlikeliness. In my biography I reveal that Malamud indeed had had a secret lover in the 1960s, a young student. I was told that Roth (who had refused to cooperate in the research for my biography, perhaps because he didn’t feel it should be written from outside America) was astonished that what he had imagined was in fact true.

But there were other, better gifts—seemingly little things, like a revision Malamud made late in his writing of The Fixer. It is perhaps Malamud’s most Jewish novel, set in Kiev and based on the Beilis trial of 1913, the unjust imprisonment of a Jew in late Tsarist Russia. In the novel only one man—the liberal magistrate Bibikov—has been righteous in defense of the Jew, the odd-job fixer Yakov Bok. And for his efforts, Bibikov is imprisoned, and hangs himself in the cell next door. Near the end of the novel, Yakov has a fantasy about killing his enemies, assassinating the Tsar:

As he raises his revolver on behalf of his people, the fixer cries, “This is also for the prison, the poison, the six daily searches. It’s for Bibikov and Kogin and for a lot more that I won’t even mention.”

And then, between his pointing the gun and pulling the trigger, Malamud inserts this, in a mere parenthetical:

(though Bibikov, flailing his white arms, cried no no no no)

There is Malamud’s return from fantasy; there is the magistrate’s spirit still clinging to his humanism despite the call for revenge at his own death.

Such for me were the gifts of the writer made beautifully, morally plain in the tiniest of great moves. This is what Malamud called, in a lecture series given at Bennington, “the human sentence.” It is what I discovered again and again in the archives and manuscripts, like looking over Malamud’s shoulder as he wrote.

LOA: Where can we see Malamud’s influence on subsequent generations of writers? What unique qualities did Malamud introduce to American fiction, and how does his legacy persist in the contemporary literary landscape?

Davis: Specific influences aren’t always easy to clinch. There are of course Malamud’s pupils—Katha Pollitt and Jay Cantor, say, or the late flowering of Arlene Heyman as a novelist (it is partly through her generosity that the third volume of the LOA Malamud has finally appeared).

There are admirers in Joyce Carol Oates, Cynthia Ozick, Bharati Mukherjee, Steve Stern, Kevin Baker, Téa Obreht, Nicole Krauss, Aleksandar Hemon, Jonathan Lethem, Jonathan Rosen, and Boris Fishman. Also, I imagine, other Jewish writers such as Nathan Englander and Michael Chabon. And I like to think that somewhere at the heart of the American short story Malamud is present still in the warmth and idealism of Tobias Wolff and George Saunders.

And that is part of what I hope is my bigger, more general point about Malamud as a representative of something tenderly vital in the history of the American soul and heart, which is what makes the Library of America a rightful home and fortress for his work, for the protection and promotion of his living heritage.

I felt this heritage as very much a living experience when I was reading Jonathan Safran Foer’s Here I Am. I had that novel with me at a difficult time, sitting by the bed of my mother during her last days in a nursing home, so admittedly my feelings were raw and maybe skewed. But suddenly, when that novel became most straight and serious to me, I thought here is Malamud again, not necessarily known or specific, but what he stood for as a representative of Jewish feeling, itself no more than the representative of something unapologetically and unavoidably emotional in the human heart. Foer writes, “She knew he was a Hebrew because only Jews cry silently”—not literally or utterly true, of course, but rather so because, as Malamud put it, “there are Jews everywhere,” including those who formally aren’t.

Shortly before Malamud died, in 1986, he was visited by a colleague from Bennington, Claude Fredericks. Fredericks wrote me that Malamud invited him into his study to show him a Rembrandt drawing bought from the royalties for his story collection Rembrandt’s Hat:

Then he raised his hand a little higher, to where on the top shelf of his bookcase there were a number of Library of America volumes. “There someday,” he said, “I’ll be, too.”

Philip Davis is Emeritus Professor of Literature and Psychology at the University of Liverpool, where he was Director of the Centre for Research, Literature and Society. He is the author of the definitive biography, Bernard Malamud: A Writer’s Life.