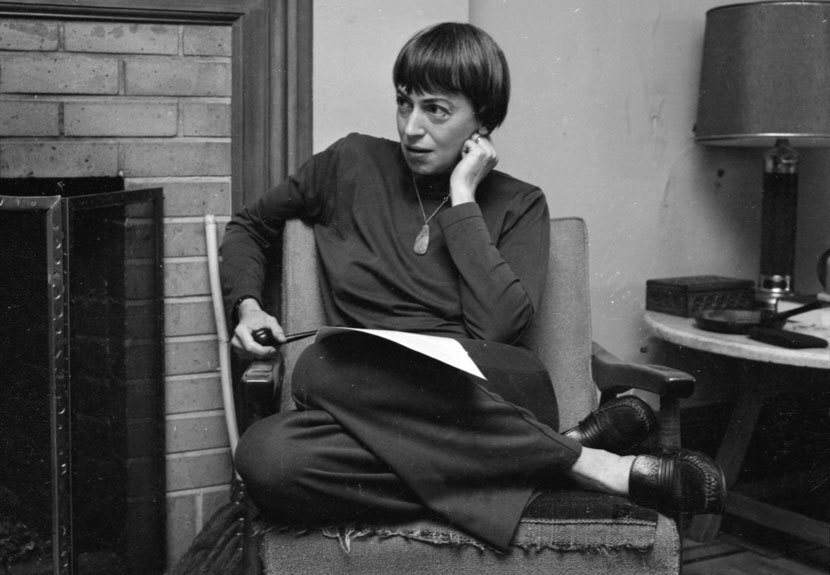

A towering figure in the world of science fiction and fantasy literature, Ursula K. Le Guin was also a prolific poet throughout her five-decade career, prompting Harold Bloom to wonder why her “inimitably individual” verse went relatively underrecognized compared to that of other great twentieth-century poets.

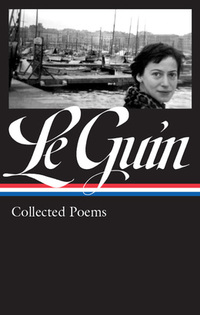

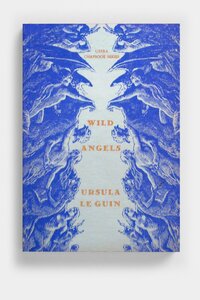

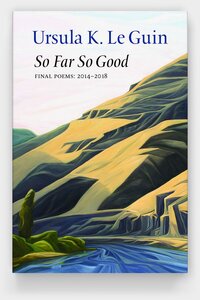

This April, LOA published the sixth volume in its definitive edition of Le Guin’s work: an authoritative gathering of her visionary, stylistically adventurous poetry, extending from 1974’s Wild Angels through So Far So Good, her final work. With an introduction by Bloom, the volume posits her as a major American poet, whose themes of nature, womanhood, bravery, and aging—found throughout her fiction—achieve their most distilled and transcendent expression in her lines and stanzas.

Via email, writer and podcast host David Naimon—who collaborated with the late writer on Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing and the Crafting with Ursula series—was generous enough to answer our questions about Le Guin’s poetic legacy, what fans of her SF can discover in her lyrics, and her “version” (not translation) of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching.

LOA: Le Guin is primarily known for her science fiction and fantasy, but both her first and last publications (“Folk Song from the Montayna Province” in 1959 and “The Cat” in 2018) were poems, and in between she published over a dozen collections of poetry. How does poetry fit into the rest of her work?

David Naimon: I think you are right to point out that poetry is the through line in her career as a writer. It was the first thing she wrote, and even after she stopped writing novels, in the last decade of her life, she continued to go to her poetry peer critique group, continued to write poetry.

How poetry fits into her career at large is an interesting question. She didn’t write science fiction poems or fantasy poems, though she didn’t have anything against either. But I think she saw poetry as a distinctly different orientation, of herself in relation to language and to the world.

In talking about how she wrote fiction Le Guin said, “I seldom exploit experience directly. I do what the poet Gary Synder calls ‘composting’—you let everything you do or think or read or feel sink down inside yourself and stay in the dark, and then (years later, maybe) something entirely new grows up out of that rich darkness. This takes patience.”

I think it is telling that she quotes a poet to describe how her fiction arises, and I suspect it is in the writing of poems where the composting begins for Le Guin. In contrast to storytelling, she considered poetry more fundamentally an act of contemplation than imagination, and yet from this act of deep listening arises concerns that recur throughout her stories, perhaps most notably how humans interact with the nonhuman “other,” whether an alien or an animal, a dragon or a forest.

I think poetry touches deep within her, to something about language that is deeper than the connotative meaning of words, that approaches music and texture, and touches the mystery of what makes us who we are and what it means to be alive.

In her speech “Deep in Admiration,” included in Library of America’s Collected Poems and first given at the “Anthropocene: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet” conference, she writes about the importance of both poetry and science, and quotes Mary Jacobus: “The regulated speech of poetry may be as close as we can get to such things—to the stilled voice of the inanimate object or the insentient standing of trees.”

LOA: In his introduction, Harold Bloom wrote: “For many years I have wondered why her poetry is relatively neglected. Her lyrics and reflections are American originals.” Has her poetry been neglected? What will poetry readers find here that may surprise them?

Naimon: I think so, at least critically. When the Poetry Foundation commissioned me to write an essay exploring what her poetry tells us about her more well-known work and how her poetry related to it, I could find very little critical or scholarly engagement with her poems to build upon. She herself has written wonderfully and deeply about poetry and has many essays and speeches that engage with it. But it felt important to seek out other voices too.

I traveled to Port Townsend, Washington, to interview Michael Wiegers at Copper Canyon Press, who published her posthumous final collection, poems written with the full knowledge that her time was limited. And Wiegers remarked that she had mentioned, in her back and forth with him as her editor, that it was the first time that she had received substantive editorial attention to her poetry.

Ursula also mentions in the introduction to the book we did together, Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing (an introduction that is quite funny, called “Fear and Loathing in the Interview”), that of our three conversations (one in each genre), it was the poetry conversation she had been nervous about. So I suppose, given that her poetry wasn’t evaluated and appraised with the seriousness of her fiction and nonfiction, you could propose a theory that perhaps she was insecure about her poetry. But I don’t think so. Rather I think poetry touches deep within her, to something about language that is deeper than the connotative meaning of words, that approaches music and texture, and touches the mystery of what makes us who we are and what it means to be alive—something that is hard to put into words, and hard to talk about in an interview.

I highly recommend listening to the episode of Crafting with Ursula with Molly Gloss, called “Writing the Clear, Clean Line.” It is the one episode (of the twelve) that focuses on poetry and there is no better person to talk about it with than Gloss. She started, decades ago, as a writing student of Le Guin’s, but they had long since been peers as SFF writers, in critique groups together in both poetry and prose. So we get to hear, from an insider’s perspective, what it is like to workshop with Le Guin. And one thing that is clear is that Ursula knew what she liked and was confident about how she wanted her poetry to be.

LOA: The power of poetry—of songs, of words themselves—seems to be a through line in Le Guin’s work, from Annals of the Western Shore to Always Coming Home to Earthsea. Why, do you think, was poetry so important to Le Guin?

Naimon: I’m glad you mention the poetry found within her fiction, particularly the poetry of the Kesh people, in a postapocalyptic California. Thinking of this future world where people find a way to not only survive but thrive, I think of something the Chilean poet Raúl Zurita said to his interviewer, the poet Forrest Gander: That poetry exists before writing. That poetry is birthed with the birth of the human. That at the moment when someone realizes that the person next to them is going to die, and that that will happen to them as well, they understand death and must develop an answer. This is the first poem. And then Zurita says something I love: “And since we are made of the same elements that stars are made of—the human, death, poetry, that is what we are made of.”

If poetry arises with the appearance of humans, before writing, it makes sense that it would need to be an integral part of Le Guin’s imagined worlds, whether on other planets or future centuries of our own.

LOA: This volume features Le Guin’s “version,” as she called it, rather than a translation, of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching. Volume editor Harold Bloom felt it belonged with her poetry. How does Le Guin’s reading of the Tao influence her work?

Naimon: When we talked together about poetry (a conversation included in this volume), I asked her, even though her preferred poetic form was the quatrain, something about haikus. In Robert Hass’s introduction to The Essential Haiku, he says haikus are attentive to time and space, grounded in a season of the year, with language that is kept plain, with accurate original images drawn from common life, and that there’s a sense of the human within the cyclical nature of the world. She said she felt very at home with this as a lens through which to view her own poetry.

In light of that, I might say one of the ways the Tao Te Ching influences her poetry is aesthetically: her deceptively simple-seeming lines that resist simple meaning. And then, philosophically, the notion of wu wei, doing by not doing—I think there is a certain decentering of the self that happens in the act of writing the type of poetry she writes.

LOA: Do you have a favorite among Le Guin’s poems?

Naimon: Yes, the poem “Leaves” from her last collection, So Far So Good. It captures so much of what mattered to Le Guin as a poet and a person: the interdependence of the human and nonhuman, the relation of language to identity and memory, the deeply human act of art-making and representation. And all of it is animated by questions of artistic legacy that echo Le Guin’s own concerns around how women artists in particular, even when quite popular in their own lifetimes, often don’t make it into the canon. It’s a poem that on a first read might seem deceptively straightforward, but is really very complex and profound, rewarding multiple readings.

David Naimon is the host of the literary podcast Between the Covers and its 2022 series Crafting with Ursula. He is also co-author with Le Guin of Ursula K. Le Guin: Conversations on Writing, a finalist for the Hugo Award and winner of the 2019 Locus Award in nonfiction. His writing can be found in Orion, AGNI, Boulevard, and Black Warrior Review, among many other places. It has received a Pushcart prize, been reprinted in Best Spiritual Literature and The Best Small Fictions, and been cited in Best American Mystery & Suspense, Best American Travel Writing, and Best American Essays.