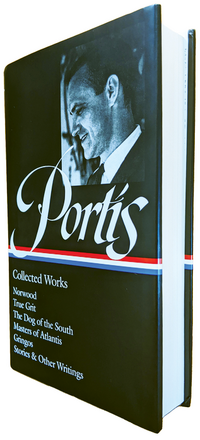

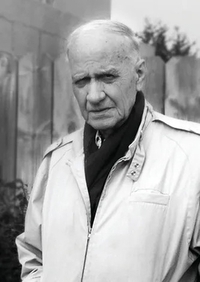

This April, Library of America published the long-awaited Charles Portis: Collected Works, gathering five novels and collected nonfiction from the beloved comic genius perhaps most famous for True Grit, the genre-defying Western told in the inimitable voice of Mattie Ross.

“Even the most outlandish of Portis plots are populated by the kind of Everymen found in almost every Zip Code in this country: barmaids, shopkeeps, shade-tree mechanics, high-and-dry hippies, would-be writers, secretaries, veterans, junkyard scrappers,” writes Casey Cep in her New Yorker review of the volume. “They are themselves a kind of Library of Americans, and Portis is excellent not only on their day jobs but also on their daydreams and stray thoughts and endogenous knowledge of the world.”

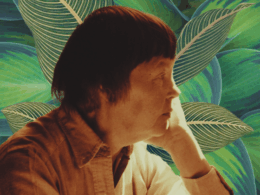

Below, volume editor Jay Jennings reflects on his time exploring an archive of Portis’s papers unearthed at the writer’s family home.

In her memoir from 2010, I Remember Nothing, Nora Ephron reveals that in the 1960s she dated Charles Portis, then a fellow early-career journalist in New York. As reporters, they subscribed to the job requirement that went on to serve each well in fiction and nonfiction alike: “Take notes.” (That succinct dictum famously makes an appearance in Ephron’s roman á clef Heartburn.)

For Portis, who died in 2020, the notes he took as groundwork for his singular fiction (five novels and a handful of stories) and his nonfiction (newspaper journalism and longer magazine reporting and essays) have remained largely obscure, as hidden and mysterious as the contents of the fictional John Selmer Dix’s lost “tin trunk that was all tied up with wire and ropes and straps” in The Dog of the South.

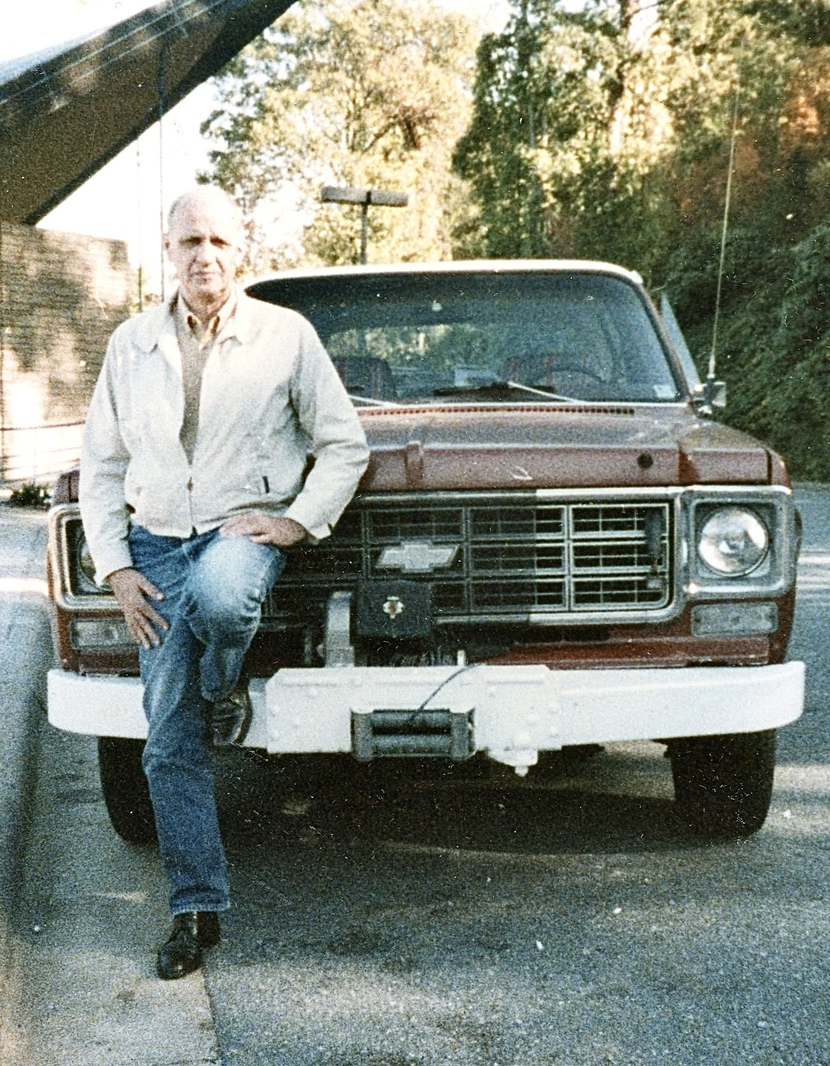

But recently, a Dix-like cache of Portis’s papers, brimming with notes, ephemera, and correspondence, emerged into the light from the basement of the Little Rock, Arkansas, house he bought for his parents with the money he earned from the sale of the movie rights to True Grit in 1968. The home has remained in the family since then, but the trove was only recently found and examined after the need for HVAC work (a very Portisian detail) uncovered it. The Portis estate and family—especially Charles’s brothers Richard and Jonathan and nephew Paul Sawyer and his wife, Nathania, a professional archivist—very kindly allowed me access to this material.

One of the most helpful categories of ephemera for me in writing the chronology for the newly published Library of America volume was gas receipts. As I laid them out to follow Portis’s peripatetic wanderings to places like Key West, Corpus Christi, San Miguel de Allende, and New Mexico, I felt uncomfortably close to Ray Midge, the cuckolded narrator of The Dog of the South who does the same with American Express receipts to trace the journey of his wife and her paramour. More substantive was the material in Portis’s own hand—and from his two-fingered typing.

The material uncovered at the Portis home might be fodder for numerous PhD theses, but the discovery only affirmed for me the mystery of artistic creation.

For the purposes of this essay, “notes” broadly refers to preparatory novel research, organization, and ideas, as well as manuscript emendations. Such a window into the mind of an exacting writer at work is fascinating, even though I’m not at all certain he would approve of my pawing through his papers, despite our trusting friendship of thirty-plus years. If I somehow had to justify myself to him now, I would argue that writing about these papers might bring him new readers. I can see him eyeing me silently for a bit, sighing, and then agreeing to let me proceed—as long as I didn’t ask him to help.

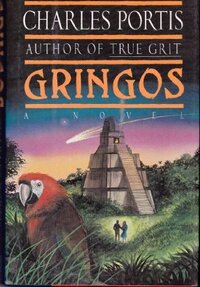

Portis’s longtime reluctance to discuss his life or his work with people he didn’t know (and often those he did) has led many of his fans to ask, in the years since his final published novel Gringos appeared in 1991: is there another novel manuscript among his papers? There have been tantalizing signals: mentions in interviews with friends or relatives of something set in Veracruz and involving chiropractors or witches. But the answer is a qualified no. The archive contains pages covering a Veracruz-witch narrative, but the sum doesn’t add up to anything publishable by Portis’s standards.

Much earlier documents from 1966—thick files of photocopies from Tulsa and Fort Worth newspapers on Bonnie and Clyde and Pretty Boy Floyd—speak to a strong interest in a historical crime novel, but those projects seem to have stalled, either because word of Warren Beatty’s upcoming film about the former reached him and discouraged him or because he found more to chew on in his research for True Grit, the writing of which was well underway by early 1967. So, the work contained in the Library of America volume, along with a selection of other writing in Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany (2012), which I also edited, gives us as complete an oeuvre as I imagine he’d like to put before readers.

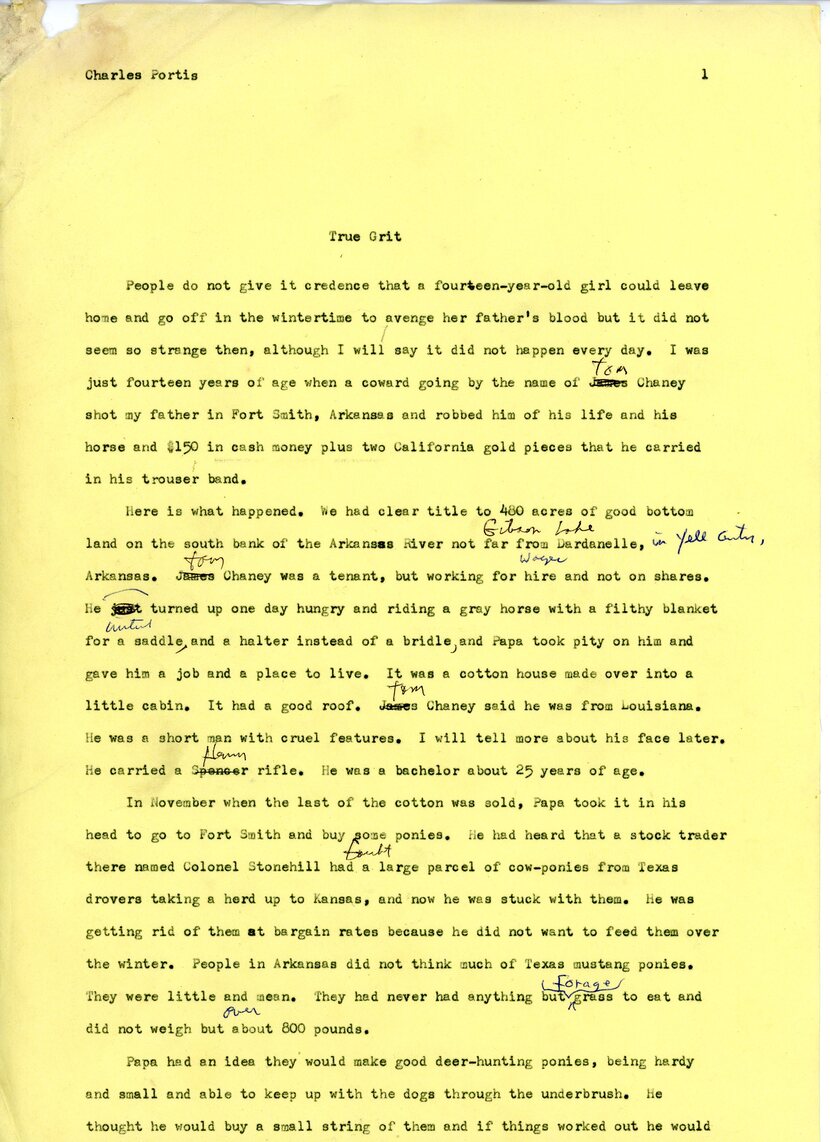

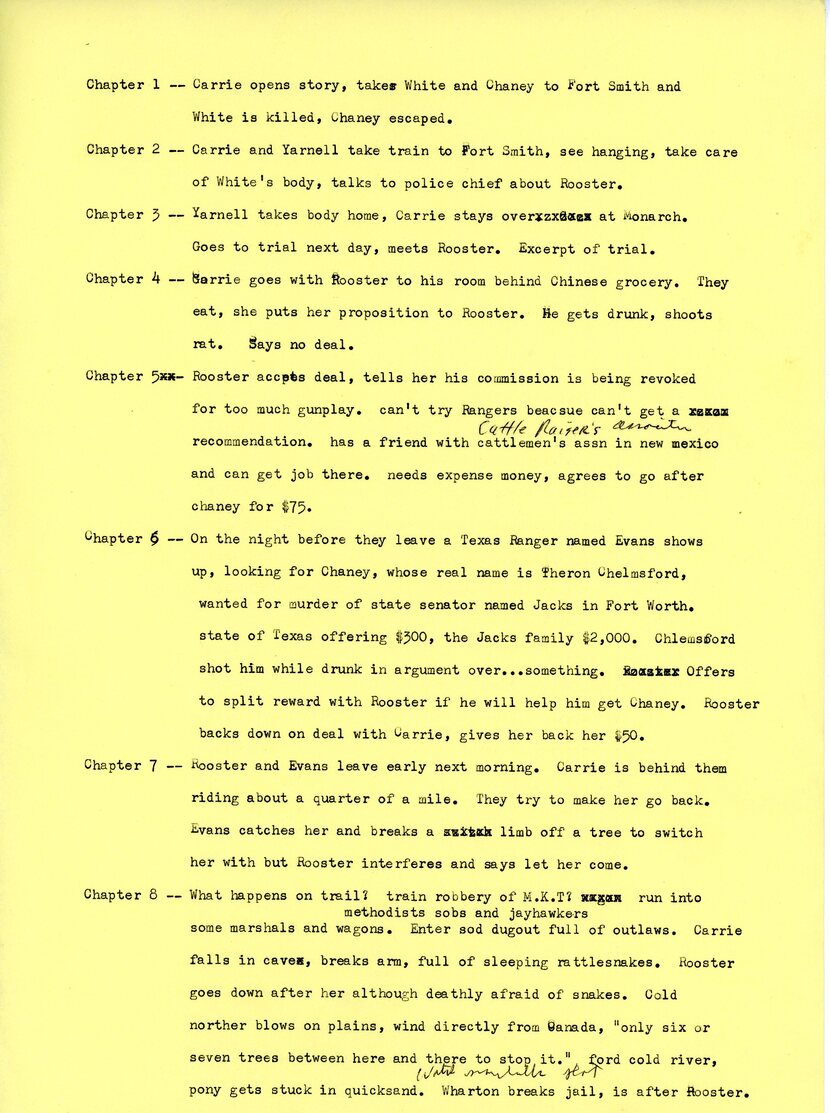

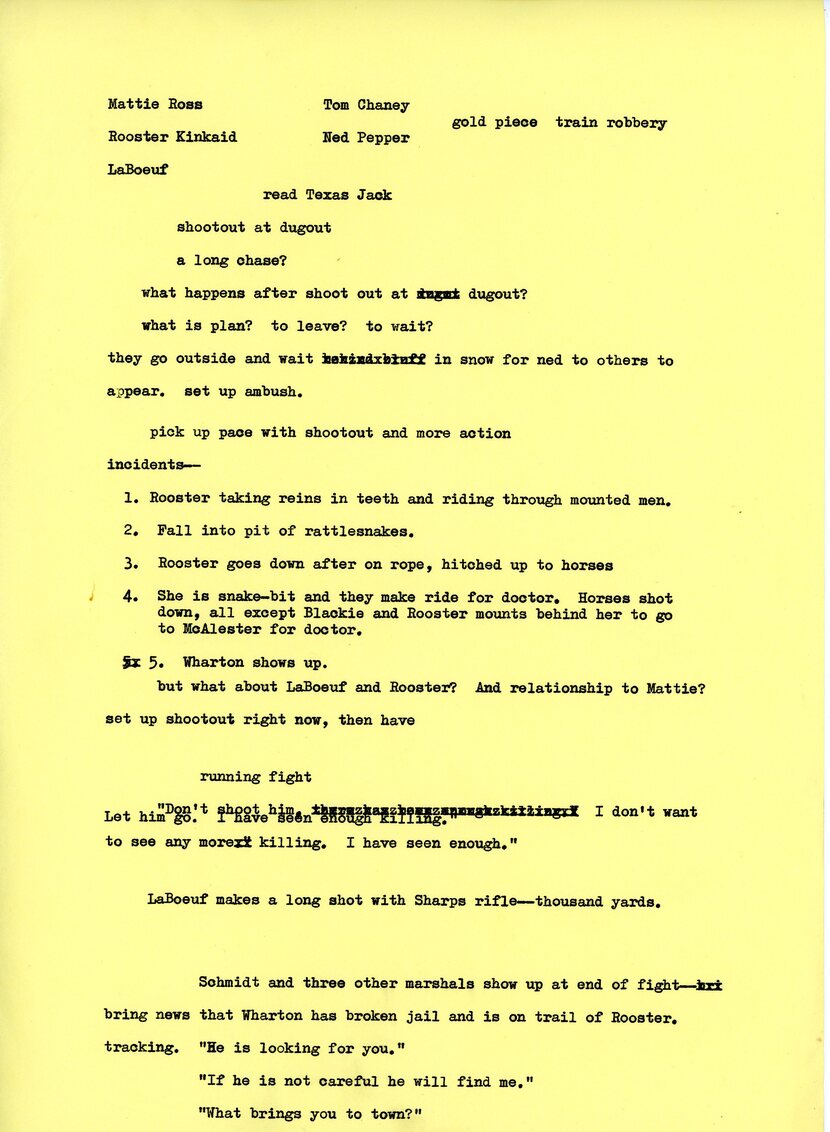

In particular, the notes and drafts and changes for True Grit are a rich vein for exploration. Early pages have the book’s indelible characters, whom I have trouble imagining under any other names, as Carrie White (for Mattie Ross), Evans (for LaBoeuf), and James Chaney (instead of Tom, which Portis changed after remembering that James Chaney was the Black civil rights activist murdered in Mississippi in 1964). Rooster was always Rooster, though in early drafts his surname is Kinkaid or Poindexter. That should put to rest any claim that the character was based on a real marshal named Cogburn. In a letter from 2000, answering questions from the superintendent of the Fort Smith National Historic Site, in the western Arkansas city where Mattie first meets and recruits Rooster, Portis said he landed on the name Cogburn because it was “Scots,” the background he wanted Rooster to have.

A very early chapter outline using those previous names—typed on yellow long bond paper (for all you archive nerds)—follows the well-known beginning of the book: “Carrie opens story”; her father is killed by Chaney; she travels to Fort Smith, witnesses a hanging, “[g]oes to trial next day,” and seeks out Rooster afterwards; Evans and Rooster team up and leave her, but she follows. By Chapter 8 of the outline, Portis is asking himself “What happens on trail?” The rattlesnake pit is there from the beginning, but a potential cattle drive will be dropped and a proposed showdown scene with Rooster and Odus Wharton, whose family history with Rooster is part of the early trial scene, winds up mentioned in the final manuscript secondhand, in Mattie’s postscript to the main events.

Portis was fond of numbering his notes. One page headed “Changes, additions,” probably late in the writing, lists ten items to sharpen details in the narrative: “2. Frank Ross fought with the First Arkansas Mounted Rifles—see notebook”; “8. Change Rooster’s pistol to .44-40 Colt’s revolver.” Many of these notes speak to the historical novelist’s fusion of imagination and accuracy, a hybrid process addressed by Portis in his letter to the Fort Smith superintendent: “[M]y ‘research’ wasn’t very professional. If I couldn’t confirm something, or locate a particular fact I needed, I would just make something up. And something much better, too, I told myself, than the dreary fact would turn out to be. I wasn’t writing a treatise, only a novel. Still, you like to get things right.”

For me, the proof of Portis’s quest for accuracy came after I’d given a talk on True Grit in Massachusetts and was approached by a man dressed as Rooster who identified himself as having been a Civil War reenactor for some forty years. He said that he and his cohort love to find mistakes in historical novels, and he’d read True Grit recently and couldn’t find anything wrong in it. Portis himself played fact-checker in his own reading, according to his copy of a 2009 book about Marines in Korea, where he corrected a reference to a “Garland M1” rifle to “Garand.” You like to get things right.

What Portis also gets so right in True Grit and his other novels is language, in all its forms: the speech of the nineteenth-century frontier (as filtered through the memory of an older Mattie Ross), drunken bar conversations, state legislative hearings, rantings of conmen and conspiracy theorists and naifs. Much of the dialogue in True Grit is worked out in notes separately from any context, exchanges from different scenes appearing on the same page. On one of these pages, the trio appears at the outlaw hut and Rooster asks, “Who all is in there?” and the reply from inside is, “There ain’t nobody in here but Methodists and sons of bitches!” Then “Methodists” is crossed out and “Baptists” written above it. The final book has it as “Methodist” (the construction of the reply is singular now rather than plural); perhaps Portis thought that Baptists, even if outlaws, were unlikely to say “son of a bitch” or, as in the book, he wanted the brother of the speaker to be a “Methodist circuit rider in south Texas.” In another version of this scene, Rooster is much more forlorn than he will be in the published book, where his posture is aggressive. He tells the criminal inside, “It is a bad night. We are soaked and frozen.”

As with historical facts, when Portis can’t find a word he needs, he makes one up. A Norwood manuscript shows the evolution of his onomatopoetic neologism “pankled” in a description of beetles burning up in a gas-field flame and falling on a house’s tin roof. He crossed out “panked” in “their little toasted corpses panked down on the roof” and added the extra syllable, objectively making the line funnier. That manuscript and those from True Grit are filled with meticulously considered phrases and rephrases, line-by-line and word-by-word assessments of how his words will land.

Obviously, the material uncovered at the Portis home might be fodder for numerous PhD theses, but the discovery only affirmed for me the mystery of artistic creation. The alchemy a writer conjures when sitting down and facing a blank sheet of paper, yellow long bond or any other, cannot be traced to research or outlines or travels reconstructed from gas receipts. Those looking for keys to how stories delight or move us are as doomed to failure as the followers of Dix in The Dog of the South, the Gnomons in Masters of Atlantis, or El Mago in Gringos. Portis himself never liked to talk about his “process.” An editor from The Paris Review once contacted me and asked if Portis might sit with me for one of the magazine’s well-known “Writers at Work” interviews. I answered, “I can’t imagine anything he would enjoy less.”

There’s one note that will never make it to an archive because I’ll never give it up. When his Alzheimer’s was beginning to emerge and he had to stop driving, Portis would walk down the hill from the apartment complex where we both happened to live to the Faded Rose restaurant and bar. We met there most Monday afternoons, and one day I offered him a ride back up the hill. I added that if he ever needed a lift, he could give me a call—from the restaurant or wherever he was (because he refused to carry a cell phone). Always prepared to observe and record, like every good novelist and journalist, he pulled a pen and pad from his pocket and asked me to write down my number. I did so and gave the pad back to him, and he looked at it for a moment, noticing a note he’d made there earlier, the only other thing on the page. He read it aloud, “Like housecats gone feral.” He considered the phrase briefly and said, “I wonder what that was all about.”

When his family found the pad among his papers after his death, they gave that page to me. It didn’t matter what it was all about; those four words—assembled in that particular way—sounded just like him.

Jay Jennings is the editor of the LOA edition of Charles Portis: Collected Works and the author of Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City. He was formerly senior editor at the Oxford American, a reporter for Sports Illustrated, and features editor at Tennis magazine. A native of Little Rock and a longtime friend of Portis, he is the editor of Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany and the co-writer (with Graham Gordy) of a screenplay adaptation of Portis’s novel The Dog of the South.