Library of America publishes the works of the pioneering historian, sociologist, editor and activist W.E.B. Du Bois in two volumes. The first, Writings, gathers three books, including the landmark 1903 essay collection The Souls of Black Folk, along with more than eighty uncollected essays and articles spanning all seven decades of his remarkably long and productive career. The second presents his monumental 1935 opus, Black Reconstruction, a book that transforms our understanding of the period that followed the Civil War as a crucial moment in the evolution of democracy in America. But nowhere in the LOA edition of Du Bois’s writings—or in any other—will you find The Black Man and the Wounded World, a book he labored over for more than two decades.

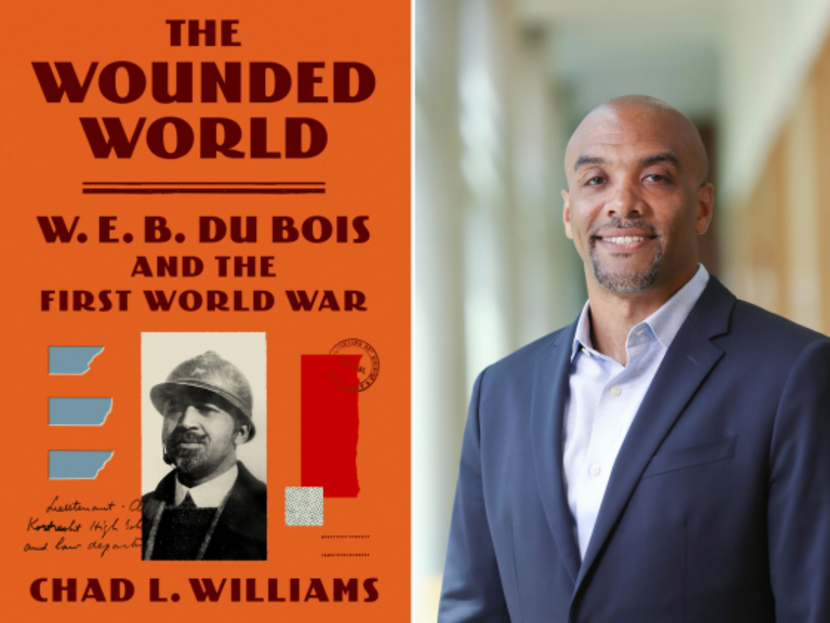

In The Wounded World: W.E.B. Du Bois and the First World War, released this April by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, historian Chad L. Williams reveals the fascinating story behind this never-completed project, which would have been one of Du Bois’s most significant works. Begun in the waning days of the First World War, the book was to be a definitive history of Black participation in the conflict and its implications for the broader struggle for racial equality in the twentieth century. It was also for Du Bois a very personal attempt to make sense for his readers, and for himself, why he had so enthusiastically supported Black engagement with the war—why it had seemed, if only fleetingly, to hold the promise of solving what he had famously described as the defining problem of American life, the problem of the color line.

We’re grateful to Professor Williams, who teaches history and African and African American studies at Brandeis University, for fielding a few questions about his new book and what it reveals about this legendary American writer and intellectual.

LOA: First, congratulations. Your book is a significant achievement, revealing new dimensions of one of the most prolific and accomplished writers of the twentieth century by focusing, ironically, on a project he was ultimately never able to finish. Was it hard to frame a story around what was, in the end, a failure?

Chad L. Williams: Failure was indeed a challenging theme to fully embrace as I wrote my book and wrestled with Du Bois’s complicated relationship to World War I. Du Bois is arguably the greatest scholar-activist in African American history and “failure” is not a word we tend to associate with him. However, I could not avoid the reality that when it came to writing what would have been the definitive history of the Black experience in World War I, he did indeed fail.

Du Bois genuinely believed that the war would mark a turning point in the history of democracy for Black people in the United States as well as throughout the broader African diaspora.

At the same time, I wanted to understand why he failed and just what that failure meant in the evolution of his life, intellectual work, and politics. Du Bois’s failure was reflective of the broader failure of World War I itself, which, as the title of his unfinished book evocatively suggested, created a wounded world. Du Bois’s own failure in believing in the potential of the war was also essential to his growth into a radical peace activist by the 1950s. Failure for Du Bois, in this sense, was both tragic as well as generative.

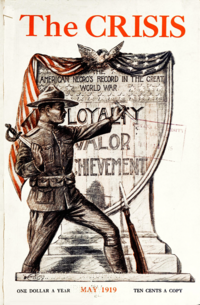

LOA: In The Guns of August, the historian Barbara Tuchman memorably described the euphoria that gripped Europeans as they marched toward war in 1914, the sense that the coming conflict would be glorious and transformative. Viewing the prospect of U.S. involvement in the war from his vantage point as the editor of The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, Du Bois seems to have been subject to something like this feeling. What did he hope the war would accomplish for Black Americans? And what did his support for the war, particularly in the July 1918 editorial “Close Ranks,” cost him?

CW: Du Bois genuinely believed that the war would mark a turning point in the history of democracy for Black people in the United States as well as throughout the broader African diaspora. He looked back to moments like the Civil War, when Black soldiers fighting for the Union Army helped African Americans achieve freedom and citizenship. Du Bois, who held a deep commitment to democracy, believed that the world war would be similarly transformative, but on an even grander stage. Woodrow Wilson’s call to make the world “safe for democracy” and the propaganda of the American war effort enraptured Du Bois. In a 1930 letter to a magazine editor, he admitted to being “swept off my feet during the world war by the emotional response of America to what seemed to be a great call to duty.” He felt that, echoing his famous formulation of “double consciousness” from his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk, the war was an opportunity to reconcile the “two-ness” of being Black and being American. In his 1940 autobiographical work Dusk of Dawn, Du Bois wrote that he “became during the World War nearer to feeling myself a real and full American than ever before or since.”

Du Bois put his credibility on the line with the “Close Ranks” editorial. In it, he encouraged African Americans to “forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.” He was widely criticized for compromising his commitments to the fight for African American equal rights, with his harshest critics branding him a traitor to the race. The uproar nearly ruined his standing as a leader. “Close Ranks” and his decision to support the war haunted Du Bois for the remainder of his life. His struggles to write and complete The Black Man and the Wounded World reflected just how wounded Du Bois himself was by the war and its legacy, both historically and personally.

LOA: In a 1915 article in The Atlantic Monthly, Du Bois had located the roots of the world war in the European scramble for imperial dominance in Africa, a contest that implicated all the major combatants. How did he reconcile this critical insight with his later advocacy?

CW: That article, “The African Roots of War,” remains one of the most analytically perceptive essays of the twentieth century. Du Bois anticipated arguments that historians of the First World War take for granted today. But at the time this was an incredibly bold thesis, reflecting Du Bois’s supreme intellect and clairvoyance. He decentered the war from Europe and saw it as a watershed moment in the future of people of African descent throughout the diaspora. In the end, he believed that the war’s horrific toll would demonstrate the incompatibility of imperialism with democracy. He also believed that the participation of African and West Indian soldiers in the French and British armies—subjects he devoted chapters to in The Black Man and the Wounded World—would advance their respective struggles for citizenship rights, self-determination, and eventual independence. His hopes certainly did not materialize in the short term. However, when viewed in the longer context of Black freedom and liberation struggles in the 1950s and 1960s, we can see how World War I planted the seeds.

LOA: Du Bois worked on The Black Man and the Wounded World in fits and starts for many years, in the process soliciting (and, sadly, failing to return) a massive archive of personal letters, testimonials, and memorabilia from Black veterans. As a practicing historian yourself, what do you make of Du Bois’s process in conceiving, researching, and writing the book? Was his inability to bring it to completion primarily owing to practical challenges, especially securing necessary funding, or was it more a function of his own deepening ambivalence about the war with the passage of time?

CW: Du Bois considered himself a scientific historian. This stemmed from his formal training at Harvard University and the University of Berlin in the late nineteenth century. He was committed to the accumulation and use of primary source material as the foundation of factual and analytically sound arguments about the past. But Du Bois faced serious obstacles in conducting traditional archival research for his book and obtaining official records from the War Department and other sources. In lieu of this, he solicited materials from Black soldiers and veterans themselves, amassing a unique personal archive that still resides at Fisk University. The archive is, on the one hand, a testament to Du Bois’s ingenuity and high historical standards. But, on the other, it is a reflection of his ego, stubbornness, and selfish belief that the materials he received were ultimately better off in his hands as opposed to those of their rightful owners.

I believe this was indeed symptomatic of Du Bois’s ambivalence and outright guilt about the war and his relationship to it. He certainly faced a number of practical obstacles in trying to complete his book over the span of two decades from the end of World War I to the start of World War II. However, he made many choices along the way that he was solely responsible for and played important roles in his book remaining unfinished. Ultimately, as I argue, the world war was a subject too big, too personal, and, as the years went on, too disillusioning for Du Bois to muster the necessary energy, focus, and fortitude to fully make sense of and translate into a coherent book.

LOA: What if Du Bois had managed to publish The Black Man and the Wounded World? How would our sense of him as a writer, and as a freedom fighter, be different?

CW: This is the great counterfactual question that I continue to ask myself. I am convinced that if published how Du Bois ultimately envisioned the book, The Black Man and the Wounded World would have stood next to Black Reconstruction as his most significant work of history. In fact, he at one point envisioned The Black Man and the Wounded World as a sequel of sorts to Black Reconstruction. The book would have demonstrated how he saw the African American struggle for democracy as a historical continuum from the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century, with Reconstruction and World War I as the pivotal moments. We would certainly have a much deeper appreciation for the importance of World War I in Du Bois’s life, work, and political evolution, as well as in African American history more broadly. The Black Man and the Wounded World would have been the definitive study of the Black experience in the war. Perhaps I would not have even felt the need to write my dissertation and first book on the subject! I certainly would have loved to read Du Bois’s book in fully finished form; part of the tragedy of the story I tell is that the world was deprived of what was destined to be a brilliant and morally urgent book about war and its failures. But even with an incomplete manuscript, Du Bois has still left us with much to consider and learn from.

Chad L. Williams is the Samuel J. and Augusta Spector Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Brandeis University and the author of Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. He has written for The Washington Post, Time, and The Atlantic, among other publications.