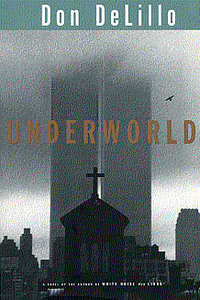

A peerless and prolific chronicler of modern America’s obsessions, fears, and fantasies, Don DeLillo has, for more than fifty years, enthralled readers with his masterful prose and searching treatments of themes—art, terrorism, consumerism, garbage—that cut to the heart of our contemporary moment. Though perhaps best known for the apocalyptic satire of White Noise and the kaleidoscopic, decades-spanning Underworld, his work has consistently linked the idiosyncratic and the personal with the universal and spectacular, conjuring fictional events, real-life characters, and razor-sharp dialogue in an inimitable yet widely influential style.

In Three Novels of the 1980s, published by Library of America in 2022, and a forthcoming volume collecting Mao II and Underworld, editor Mark Osteen guides us through DeLillo’s crowning literary achievements, making a convincing case for him as one of America’s greatest living writers.

Over email, Osteen spoke with LOA about the evolution of DeLillo’s novels, the recent White Noise film adaptation, and why so many contemporary authors try to follow in his footsteps.

LOA: LOA put out an edition of DeLillo’s novels of the 1980s last year and will publish an edition of his ’90s novels this coming fall. How did DeLillo’s work evolve through these decades? Can we see traces of the ambition and thematic range of Underworld in earlier works like The Names?

Mark Osteen: Underworld is the novel where the manifold strains in DeLillo’s previous work interlock and expand. This synthesis is novel, yet the thematic threads woven into this magnum opus are apparent not only in his 1980s work but in his earlier fiction as well. In fact, The Names itself marks a departure—embodying what DeLillo has called a “new seriousness”—that sets it apart from his early novels, even while it displays renewed attention to themes that he had introduced in those books, such as terrorism (Players, 1977) and ascetic rituals (End Zone, 1972; Running Dog, 1978).

Underworld provides a broader canvas for concerns that DeLillo has engaged with throughout his career. For example, the novel’s analysis of the apocalyptic menace of the atomic age appeared first in End Zone, where the protagonist becomes fascinated with nuclear war strategy, and of course the theme of waste shows up dramatically in White Noise, where Jack Gladney reflects upon his household’s trash. Underworld’s Fresh Kills Landfill is the Gladney garbage writ large: multiply their waste by millions and you build a veritable mountain of rubbish. Likewise, the “airborne toxic event” scene in White Noise prefigures Underworld’s attention to the dire consequences of consumerism: our products return to us as deadly poisons. Further, Underworld’s mixing of fictional characters and real people is presaged in Libra. That novel’s brilliant structure and sweep also forecast Underworld’s enormous scope.

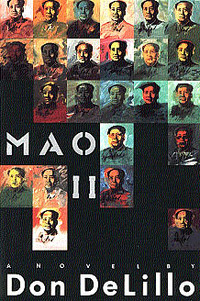

LOA: “The future belongs to crowds,” DeLillo famously writes in Mao II, and the theme of crowds and mass spectacle recurs throughout his work—perhaps most memorably in the opening of Underworld, which recounts the “Shot Heard ’Round the World” at the 1951 pennant game between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers. What is behind this fascination with crowds and their role in understanding twentieth-century America?

Osteen: But which crowds? There is more than one kind of crowd. Mao II opens with a procession tracked by the narrator’s roving camera at a mass wedding: “[T]he effect is one of transformation. From a series of linked couples they become one continuous wave,” an “undifferentiated mass.” A key word in this novel, as it is in White Noise, “mass” refers both to crowds and to the mass-produced images that they consume and that consume them. These are the kind of crowds in which characters like Karen Janney lose their identities and become subsumed into the mind of the master. Most of the crowds depicted in the novel’s words and photos—the crushed hordes at the Hillsborough soccer disaster, the mourners at Khomeini’s funeral, the brides and grooms at the Unification Church ceremony—embody this merger of the one with the many.

As DeLillo said in a 1991 interview, the mind of the terrorist and the mind of the mass organization are alike: “In both cases, it’s the death of the individual that has to be accomplished before their aims can be realized.” These crowds, DeLillo suggests, are ready to do violence, to follow any command given by the master, because their formation arises from unexpressed rage, fear, or sorrow.

As Karen perceives, the protests at Tiananmen Square illustrate the “preachment of history” that pits “[t]he motley crowd against the crowd where everyone dresses alike.” That “motley” crowd is the one attending the baseball game that opens Underworld. DeLillo’s narrator writes that the cheering spectators become “the force of some abject faith, a desperate kind of will toward magic and accident.” Such communal rituals neither separate out the individuals nor transform them into a mass mind; rather, these public rites foster and cement community, make people “want to be in the streets, joined with others, telling others what has happened.” Events like the playoff game bind people “to a memory with protective power”; ultimately, such events engender what he calls “the people’s history,” a counter-history to the official one.

LOA: Artists, novelists, terrorists, and assassins frequently share the stage in DeLillo’s novels (Nan Graham, DeLillo’s editor at Viking, once noted that DeLillo kept two folders while working on Mao II, one marked “art” and one marked “terror”). What connections does DeLillo draw between artistic work and terrorism? How are these seemingly divergent concepts related in his imagination?

Osteen: In an interview conducted around the time Mao II was published, DeLillo said, “There is a deep narrative structure to terrorist acts, and they infiltrate and alter consciousness in ways that writers used to aspire to.” I would note that he stated and dramatized these ideas ten years before 9/11. In my book on DeLillo’s fiction, American Magic and Dread, I argue that Mao II announces the end of the grand narrative of modernist authority and its replacement by what I call “spectacular authorship”: the power to use images to manufacture spectacular events that mold public consciousness.

His sentences sneak up on you; they seem effortless but are beautifully sculpted and gorgeously rhythmic. In interviews, DeLillo often describes his delight in watching the words form on the page (produced with a manual typewriter), hearing them and feeling them as they appear.

In my book I argue that terrorist acts are always mediated by the journalists, photographers, and others who record and comment upon terrorist actions (nowadays, the mediators can be ordinary citizens with smartphones). Therefore, terrorists don’t ultimately control the consequences of their spectacles, because they rely on the participation of those who transmit the images. In that sense, control of the public mind (always fleeting and partial) really belongs to the media corporations who disseminate images, memes, and words. In that way, terrorists are already “incorporated”: the dread they generate becomes another branded commodity.

Ultimately, terrorists do not possess the singular authority that Mao II’s writer-protagonist Bill Gray posits; no form of authorship does. Terrorist authorship submits to the same proliferating mediation as other forms of communication. In contrast, serious writers, DeLillo insists, must refuse to be “incorporated into the ambient noise. This is why we need the writer in opposition, the novelist who writes against power, who writes against the corporation or the state or the whole apparatus of assimilation.” According to this formulation, the novelist can escape incorporation when the terrorist cannot.

Mao II also points to an alternate, perhaps superior, form of authorship, represented not by Gray but by the photographer Brita Nilsson, who shoots both writers and terrorists. Mao II’s original dust jacket and its interpolated photos—all but one of them a crowd scene—illustrate the argument that “the future belongs to crowds,” but also suggest that the photographic image is a kind of crowd in itself. That is, photos both represent crowds and, by inviting the viewer into the picture, generate a new crowd. In that sense, Mao II presents itself as a multimedia event, a written text that also includes a crowd of photos. DeLillo’s use of photos displays his participation in the culture of images that Gray abhors, and his construction of a novel form of authorship, one that is communal, participatory, flexible. This is the kind of authorship that DeLillo advocates in the novel, one that, he believes, offers a viable alternative both to terrorists’ spectacular narratives and to the insularity of the Bill Grays of the world.

LOA: White Noise is perhaps DeLillo’s most beloved and popular work. What explains its enduring appeal to readers (and what did you make of Noah Baumbach’s recent film adaptation)?

Osteen: When I first read White Noise, I was immediately knocked out by its humor. I knew, from reading End Zone, that DeLillo could be funny, but White Noise’s humor is warmer and more generous than End Zone’s. It contains several hilarious scenes and touches: Jack and Babette’s discussion of “entering”; Steffi’s defense of “her” bath dirt; the absurdly competitive debates of the American Environments faculty (everyone loves lampooning academics, academics most of all); Heinrich’s precocious expertise; the tabloid headlines and stories; Murray’s (faux?) ingenuous praise of supermarkets and car-crash movies. The humor also emerges from Jack Gladney’s singular voice—bemused, questioning, restless, guilty, haunted. So humor is one reason for its enduring appeal.

Yet White Noise is also a deeply serious portrayal of middle-aged people experiencing existential crises, paralyzed by the fear of death. This theme pertains to every human, particularly those of us who have lived more than a few decades, and it’s one of DeLillo’s perennial obsessions. White Noise is also a celebration of the post-nuclear family, an anatomy of jealousy and male violence, and an exploration of the lingering influence of Hitler and World War II (which DeLillo earlier dramatized in Running Dog). It offers a rich menu of provocative themes.

But perhaps its most compelling (not to mention chilling) element is the airborne toxic event. Not only has this section furnished a name for at least one alt-rock band, it is still relevant because real-world conditions have not improved. This fact stung Americans again very recently, when a derailment in East Palestine, OH, spewed poisonous chemicals into the air and water. I almost chuckled, in fact, when one news source called the cloud a “feathery plume”—a phrase used to describe the toxic spill in White Noise!

Baumbach’s film adaptation has a number of wonderful moments: the airborne toxic event section is rendered sharply and eerily; many of the humorous moments are depicted faithfully. For years I’ve maintained that White Noise is unfilmable, mostly because of Gladney’s voice: that elusive tone, deftly sliding from deadpan satire to fear of death, seemed impossible to capture. Baumbach’s movie does not capture it either. I also question a few of the casting choices (I have loved Don Cheadle’s work in other roles but he seems miscast here) as well as the bewildering decision to have Babette present when Jack confronts Willie Mink in the motel. DeLillo’s own comment to me about the movie was typically pithy: it should have been shorter.

LOA: Many contemporary writers—David Foster Wallace, Jonathan Franzen, Zadie Smith, and others—have either claimed or been associated with DeLillo’s influence. Do you see widespread traces of DeLillo’s approach and ideas in contemporary fiction? And, conversely, what unique aspects of DeLillo’s art seem to have eluded his literary descendants?

Osteen: I detect traces of DeLillo’s influence in the work of many contemporary writers. For example, Jennifer Egan’s recent The Candy House displays several DeLilloesque features: its broad sweep and multiple characters recall Underworld, as does her analysis of how aspiration can turn into obsession and corruption, and her delineation of the all-encompassing power of electronic media (some of these features were also present in her earlier novel A Visit from the Goon Squad). Anyone writing about rock music culture, like Egan, owes a debt to DeLillo’s Great Jones Street (1973), probably the first literary rock novel. A fiction writer friend of mine recently told me that White Noise is one of his top ten novels of all time—less so for the themes I’ve mentioned than for its seemingly relaxed but taut structure and its brilliant employment of voice and character.

What the authors you name—all of them serious novelists who have produced important works—cannot emulate, let alone surpass, is DeLillo’s prose. His sentences sneak up on you; they seem effortless but are beautifully sculpted and gorgeously rhythmic. In interviews, DeLillo often describes his delight in watching the words form on the page (produced with a manual typewriter), hearing them and feeling them as they appear. And nobody writes dialogue like Don DeLillo. I love how his characters don’t always respond to each other directly: they engage in side-by-side monologues, reply to an earlier remark several minutes later, speak in telegraphic phrases. This is how real people talk. Very few writers have come close to his brilliance at this novelistic skill.

LOA: What underread or underappreciated DeLillo work would you recommend to readers who might only be familiar with White Noise or Underworld?

Osteen: DeLillo is best known—rightly so—for the five novels from the 1980s and ’90s. To someone who has read only White Noise and Underworld, I’d say: now read Libra. Although it is not exactly underappreciated, it’s the natural next step for anyone who enjoyed Underworld: the earlier novel has something of the later book’s ambition and scope, and also portrays both fictional and real-life characters. Of course, many Americans remain fascinated by the Kennedy assassination, and this is the best novel, by far, about the tragedy. Perhaps its most outstanding feature is its portrayal of Lee Oswald, who comes across as a complex and fascinating person: not a villain or a monster, but an ambitious, confused, and exploited young man.

The six novels that DeLillo published in the 1970s are neglected even by most DeLillo scholars. Yet they are all worth reading: Americana (1971) for its incisive treatment of advertising, movies, and American identity, themes DeLillo returns to in later novels; End Zone for its witty dialogue and anatomy of war games (including college football); Great Jones Street for its penetrating examination of the trap of celebrity, whereby even withdrawal from the public eye becomes part of that celebrity (I hope Bob Dylan has read it!); Ratner’s Star (1976), the least read of all DeLillo’s novels, for its visionary rendering of human history as a loop; Players as a compact forerunner of Libra and The Names; and Running Dog for the meticulous plotting and analysis of terrorism that anticipate Libra and The Names. Of the early works, the richest is probably Americana. Although it lacks the surgically precise, sculpted prose of the later novels, its ambition and scope most clearly anticipate his major works. And don’t forget the plays: Valparaiso (1999) is especially smashing!

Much of his post-Underworld fiction has been deemed minor, in some cases simply because the books are short. That is a mistake. Although brief, The Body Artist (2001) highlights some of DeLillo’s most lyrical prose in its intense treatment of grief and recovery. Point Omega (2010) brilliantly blends a meditation on voyeurism (playing riffs upon Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Douglas Gordon’s video installation 24 Hour Psycho) with an indictment of the “war on terror.” Perhaps his best “late” work is Zero K, from 2016; I believe DeLillo himself considers it his best post-2000 novel, and it is the one I would recommend to readers unfamiliar with his later fiction. It too portrays how the fear of death drives us to desperate measures, in this case, the construction of a cryogenics installation; it also tracks a troubled father-son relationship, and features one of the most resonant conclusions in DeLillo’s entire oeuvre.

Mark Osteen is the author of American Magic and Dread: Don DeLillo’s Dialogue with Culture and the editor of the Viking Critical Edition of White Noise. He is Professor of English at Loyola University Maryland.