O. Henry (1862–1910)

From O. Henry: 101 Stories

In April 1898, 125 years ago, William Sydney Porter became Prisoner Number 30664 at the Ohio Federal Penitentiary. During the three years he served for embezzlement from a bank in Austin, he began writing stories, poems, and small humor items and submitting them under several aliases—including O. Henry, the name by which he became famous.

Porter had it easier than most prisoners. A trained pharmacist, he was soon assigned to be night druggist in the prison hospital and given his own apartment in the hospital wing. Still, what he saw appalled him. “I never imagined human life was held as cheap as it is here,” he wrote to his father-in-law in a letter describing the torture and horrors he witnessed. “The men are regarded as animals without soul or feeling.”

Porter avoided entanglements with the schemes and affairs of his fellow prisoners, but he provided a ready ear to their stories and managed to make a few friends. “O. Henry liked the western prisoners, those from Arizona, Texas, and Indian Territory, and he got stories from them all and retold them in the office,” John Thomas, the institution’s chief physician, remembered. “He would spend two or three hours on the range or tiers of cells every night and knew most of the prisoners and their life stories.” For a period, Porter joined two other embezzlers, two train robbers, and one forger in the Recluse Club, a group that met secretly (and against prison rules) on Sundays.

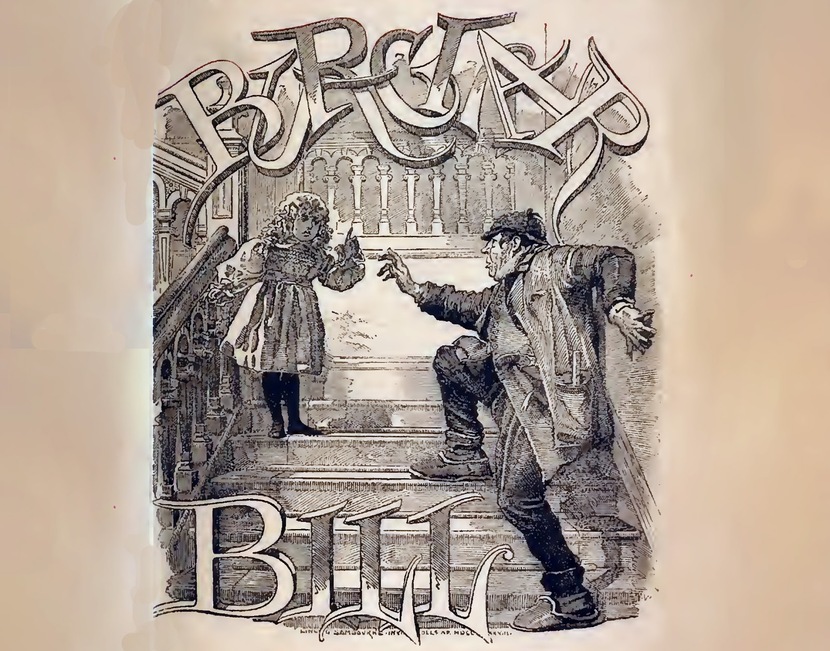

His stories from the decade after he left prison, then, are populated by scam artists, burglars, and thieves. Portrayed comically and even sympathetically, these characters range from bumbling fools (like the kidnappers in “The Ransom of Red Chief”) to hard-knocks men whose basic decency resurfaces when put to the test (like Jimmy Valentine, the safecracker in “A Retrieved Reformation”).

Then there’s the gruff crook in “Tommy’s Burglar,” a story that skewers all the sentimental Victorian-era tales about hardened criminals who encounter children during the commission of their crimes. In the version imagined by O. Henry, both the burglar and a small boy commit the ultimate offense: rebelling against the author.

You can find “Tommy’s Burglar” at our Story of the Week site, with an introduction describing the target of O. Henry’s parody: Frances Hodson Burnett’s children’s novel Editha’s Burglar.