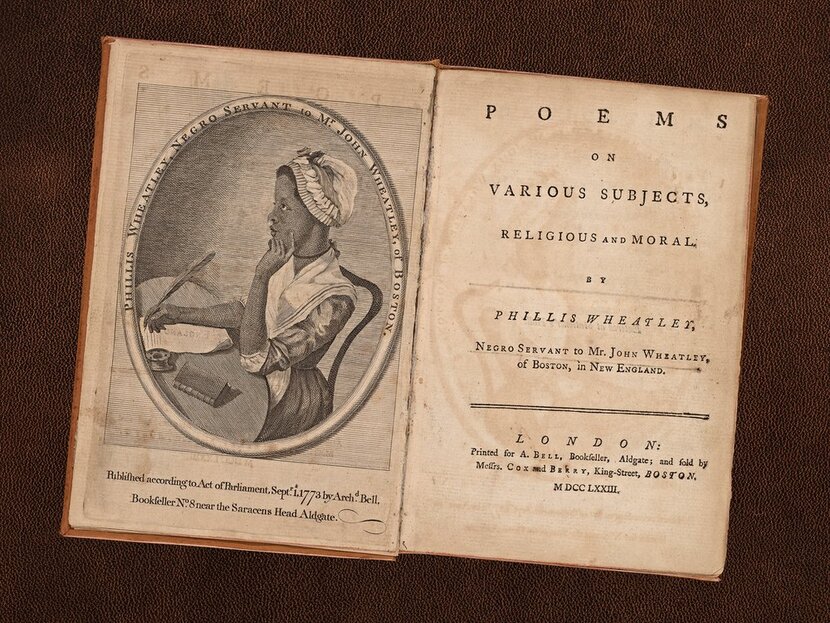

In 1761, a young girl of seven or eight—we don’t know her name—was kidnapped from her home in the Senegambian region of West Africa and brought to Boston, capital of the British North American province of Massachusetts Bay, aboard the merchant ship Phillis. There she was purchased by John Wheatley, a wealthy tailor, as a servant for his wife, Susanna. In time, the enslaved child, who was renamed for the ship on which she arrived, demonstrated a prodigious facility with language and learned to read. Within a handful of years, she began composing the poems that would make her famous as the first African and just the third woman in colonial America to publish a book of verse.

Always a contested figure—George Washington celebrated her “great poetical Talents” while Thomas Jefferson dismissed her as “below the dignity of criticism”—Phillis Wheatley has sometimes been seen as a curiosity, an outlier, and even as her profile as a trailblazer has risen, her classical style has grown more and more remote from modern readers.

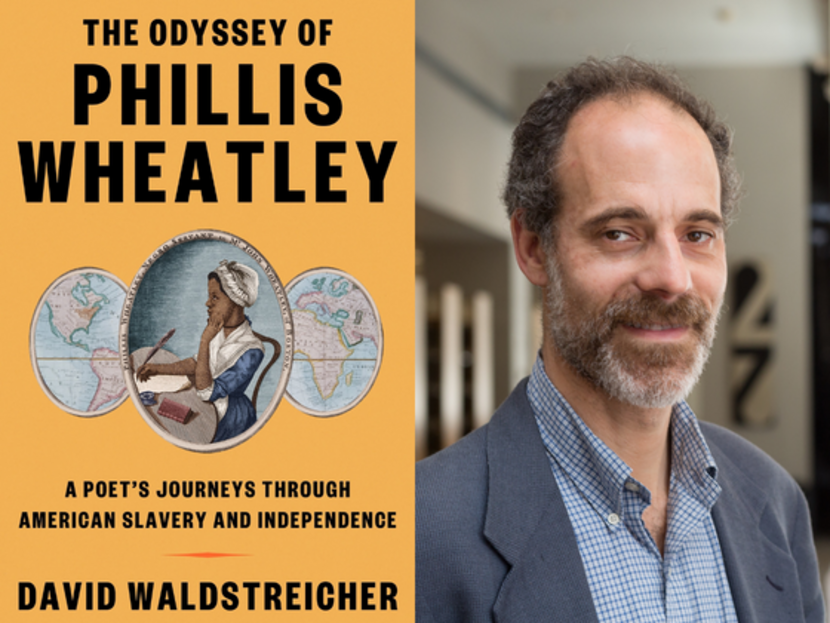

David Waldstreicher’s magisterial new biography, The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence, out this week from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, promises to transform our understanding of this essential American voice. It reintroduces us to a woman “known so well by her name,” as poet Rowan Ricardo Phillips writes, “and yet so little by the facts, motivations, and nuances of her extraordinary life.” The book has already garnered enviable coverage, from starred reviews to a feature article by Farah Jasmine Griffin in Oprah Daily.

Waldstreicher, a professor of history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, was kind enough to take time out to answer a few questions as his much-anticipated biography arrives in bookstores.

LOA: Congratulations on the new book. Early readers are clearly responding to the fuller portrait of Phillis Wheatley you provide, one deeply rooted in the vibrant social and political life in provincial Boston and metropolitan London. Immersion in contemporary newspapers, in particular, seems to have been an essential strategy for you, enabling you to contextualize Wheatley’s literary performances within both the imperial crisis that preceded the American Revolution and within the related debate over slavery in the empire. Can you describe your research for the book?

Waldstreicher: I touched on Wheatley in several earlier projects (my first book, about nationalism and political culture, and my second, about Benjamin Franklin and slavery), and I wrote a few essays based on the usual published sources. I knew I had a story to tell about Wheatley as a more political and responsive poet, an interpretation that grew from my specialties in the period and in the study of slavery and antislavery and race.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., was right decades ago when he observed that her firstness and Black genius status has made it harder to actually read her poems and appreciate her as an artist. This is why it was especially important to me to tell a story in which her poems were actions that changed her life, as poems.

But I didn’t know for certain I had a book or feel fully comfortable writing the kind of historical and literary biography that Wheatley deserves—and just as importantly, I could not settle on how to start the story—until I had a better grounding in West African history in the mid-eighteenth century and in Greek and Roman classics. Once I had those essential beginnings of her story—as the title suggests—the relationships that mattered seemed to fall into place: Wheatley realizing that this ancient Mediterranean world, a world of war and ships and gods and enslavement and exiles and crafty women, could enable her to talk about her experiences indirectly.

Then I could return to the newspapers. I looked at every page of every newspaper published in Boston between 1761 and 1784. I had once read period newspapers for runaway slaves and servants and printers like Franklin, so I knew there would likely be more there, literally and between the lines, as it were, about Black people and their enslavers and their allies than previous scholars noticed. I also read every book I was sure Wheatley had read, researched every person she knew or wrote about, which yielded plenty of new clues. You have to do these things to write about a person when only a dozen and a half of her letters have survived.

LOA: Another boon from your work in the newspapers is the discovery of fourteen anonymously published poems that you tentatively, but persuasively, attribute to Wheatley. What do these poems reveal about Wheatley, both as an artist and as a manager of her own authorial profile?

Waldstreicher: They show her range, in different poetic genres, and her sustained productivity beyond the publication of her book in 1773. Some of them suggest her continued political engagement, her responsiveness to specific events during the imperial crisis and Revolutionary War. They also suggest her strategizing, trying to retain control over her work and reputation, and perhaps also a certain playfulness, a pleasure in the veil of anonymity that most women who wrote and published poetry took for granted as the default.

LOA: As an enslaved person and a literary celebrity, Wheatley occupied a complex space in Boston society. As you note, she used “African” to refer to herself and to other people of color, but in her published elegies she clearly sought to identify herself with her mostly white audiences, both in Massachusetts and in Great Britain, and in her odes with the classical tradition that was so central to transatlantic British culture in the eighteenth century. You recount Wheatley’s many journeys, but her relation to the larger American journey from empire to independence that she lived through is ambiguous. What does her experience of it, her role in it, teach us about the American Revolution?

Waldstreicher: The ambiguity is telling—about ordinary people and Black people’s experiences, for one, which were more complicated than divisions between “patriot” and “Tory,” or even anti- and proslavery, tend to suggest. As in any civil war, people chose sides or avoided doing so for reasons that were contingent, local, and specific to them.

Wheatley brilliantly hedged her bets until it was no longer possible to do so. This was a more contingent and complicated process than what her previous biographer, Vincent Carretta, in a formulation that was pathbreaking when he proposed it twenty years ago, once referred to as her “choice of identity” between being British (and staying in London in 1773) and being American.

At the same time, I maintain that Wheatley was typical or representative in that the Revolution led both to her emancipation and to the loss of patronage and, as has been argued by others, her tragic end—though I think drawing too direct a line there tends to obscure her choice to marry and start a family, which for her surely meant freedom. The Revolution, as I put it, both strengthened and weakened slavery: it both heightened and lessened the role of slavery and of race in her life.

LOA: Your book is a significant work of literary analysis, revealing new layers of complexity in poems that have often been read one-dimensionally. This is perhaps nowhere more true than in what may be Wheatley’s best known and most controversial poem, “On being brought from Africa to America,” which seems on its face to accept the religious rationale for slavery and the slave trade:

’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

But there is a challenge in the poem, an exposure of the reality of slavery embedded in the play of words keyed to the sugar trade on which New England’s fortunes rested. For all her renown, do we appreciate Wheatley enough as an artist today?

Waldstreicher: We don’t. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., was right decades ago when he observed that her firstness and Black genius status has made it harder to actually read her poems and appreciate her as an artist. This is why it was especially important to me to tell a story in which her poems were actions that changed her life, as poems.

Throughout the project I found that understanding various cultural and political contexts—not just the general ones of slavery and of Boston during the imperial crisis, but the much more specific moments and audiences she wrote particular poems for—better helped me appreciate Wheatley’s subtlety and her writerly choices.

A minor theme in my book is the suggestion that perhaps because she experienced life under a microscope as an enslaved, racialized person, a young person, a woman, and as a celebrity, her work became increasingly self-reflexive, about herself, her identities, and about writing. She experimented in a variety of genres and voices too, so early, in ways that suggest astonishing growth and multicultural literacy.

LOA: Wheatley has often been seen as a singular figure, but throughout your book you situate her in relation to other people of color, especially other Black writers (Library of America will do something similar in the forthcoming volume Black Writers of the Founding Era). How does our expanding sense of the vibrancy and diversity of African American writing in the era of the Revolution change the way we read Wheatley?

Waldstreicher: Her membership in what I call a cohort of young Africans or creatives can enhance our sense of her careful artistic and political choices—and also even of the odds against her short- and long-term success. There were no established career paths for poets, much less for Black female artists of any kind. What’s amazing is how much they tried, how much Black writing survived and how interesting, eloquent, and even politically effective much of it was.

David Waldstreicher is Distinguished Professor of History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of Slavery’s Constitution: From Revolution to Ratification and Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution. He has written for The New York Times Book Review, the Boston Review, and The Atlantic, among other publications. For Library of America he has edited, in two volumes, The Diaries of John Quincy Adams.