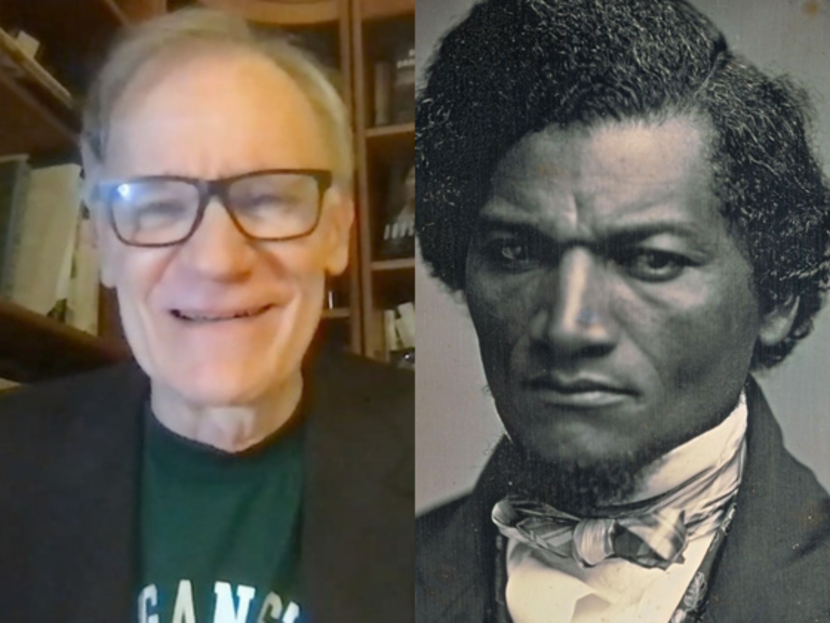

This February, distinguished historian David W. Blight joined Library of America for the LOA Live program “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” to discuss the extraordinary life and legacy of the man who escaped slavery to become one of the nation’s greatest orators and writers.

In this condensed and edited transcript of his remarks, Blight shares insights on Douglass’s complexity as a political and literary figure, the influences of religion, war, and Reconstruction on his thinking, and the approach that informed the recent LOA edition of Douglass’s speeches and writings, edited by Blight.

The full program is available to watch on YouTube.

Douglass as a writer

I want to start with a little background on Douglass, and perhaps a little bit about why we’re still here in the twenty-first century talking about him, writing about him, and indeed, reading him. It used to be that if Americans knew much about Frederick Douglass, they knew the young Douglass, the heroic story of his life as a slave and then his escape at age 20. But they may not know the scope and scale of this life, nor the scope and scale of this man as an orator and writer.

He wrote millions of words. He wrote hundreds and hundreds of shorter-form editorials in his own newspaper and other places. He became a great essayist. He also wrote 1,200 pages of autobiography. He wrote one novella. And then there are the thousands of speeches, which were hard to select [for the LOA volume] because there are so many of them, and so many of them range from good to masterpieces.

For a long time I’ve believed that if Douglass were here today and some of us could ask him, “Sir, what are you most proud of in your life? What do you most want to be recalled for?”, I suspect he would say, “I was a writer. I was a writer in a world that didn’t believe Black people were really writers.” It was a world where a lot of famous and important philosophers had said that Africans and most of their descendants were people without language.

But he became, first and foremost, a kind of prose poet of American democracy; a prose poet of what slavery had meant in America; a prose poet of what the U.S. Constitution could mean; a prose poet of what the Bill of Rights could mean; a prose poet of what it even means to be an American, especially through that epic history of the run-up to the Civil War, the huge crisis over slavery, the destruction of the Union, the all-out war for the preservation of the Union and the destruction of slavery, and then the dozen-year or so period we call Reconstruction, when the United States, in its Constitution, in its polity, and in its position in the world, remade itself. He’s a prose poet of that entire story. And he’s even a prose poet, eventually, of the retreat from all those victories.

Douglass’s eloquence

He had a certain kind of unsurpassed eloquence, which is not always easy to explain. Think of any great thinker, all your favorite writers—how did they become that way? How did they learn to hear the music of words in their head? And how did they get them on paper, in story, in analysis, in poetry?

He had an eloquence that came from deep within a remarkable mind, though his literacy was not something he totally made on his own. He had teachers, he had help here and there, although he never spent one day of his life in a formal schoolroom or classroom. But it comes from his experience as well.

Eloquence comes from having something to say, it comes from a place where you want to tell people what has happened to you, what is happening to your people, what is happening in the world. He had an eloquence about explaining the physical and mental terms of the slavery experience. And Douglass said over and over, especially in the autobiographies, but elsewhere too, that it was not the physical anguish of enslavement that bothered him most, it was the mental, psychological, intellectual humiliation of slavery. There is no better analysis in the nineteenth century, and maybe no one’s improved on it since, of this inner world of what an enslaved person experiences as they survive it.

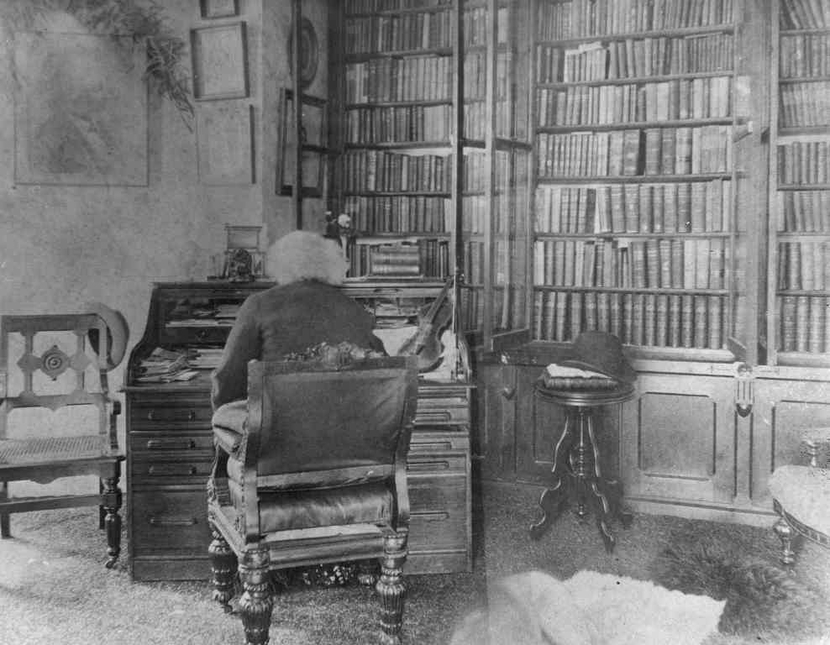

He expressed himself in oratory, but also the written page. Every major Frederick Douglass speech, almost all of them in this volume, exist in a typescript or a written form. This is not a man who just walked into halls and churches and blew out the lights with extemporaneous oratory. He could do that, and he frequently broke from his script. But he wrote these speeches down, some of them in twenty- to thirty-page texts. And I’ve always found that fascinating, because Douglass was the kind of person, like perhaps a lot of us, who didn’t really know what he thought about something—a problem, a story, a question, a great crisis, the Dred Scott decision, or whatever—until he went to his desk and wrote it.

Prophets are people of words who can find the language in great crises, in turning points in history, when people are in despair or even when they’re in glee and happiness. They can find the words to help us understand what we’re going through, what it means.

He spoke as a writer with a kind of terrible honesty, and at times a savage irony—our man was an ironist, through and through—of both the power of America’s creeds, of its promises, but also the hypocrisy of its practices. Perhaps no one else in the nineteenth century examined American hypocrisy on race and slavery quite like Douglass did in the greatest of his speeches, the “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” address of 1852.

To see and hear Frederick Douglass became a kind of an American wonder in the nineteenth century. There were European tourists who came to America—at least after the Civil War—who wanted to see the wonders of America, but sometimes on the list was, could you see Frederick Douglass speak? Could you be at that event? He attained this kind of what we’d call rock-star status as a performing orator.

The many sides of Douglass

He’s a creature of paradox, a creature of contradictions. He never stays put, which is one of the things that makes him fascinating. He could be at times a radical thinker about certain kinds of revolutionary politics, even, in the late 1850s, the possible uses of revolutionary violence. But he was also almost always an advocate of political liberalism, that is, the nineteenth century’s notions of liberalism, the faith that great change comes only through law, through institutions. He preferred institutional change, legal change, constitutional change, to violent change, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t consider it.

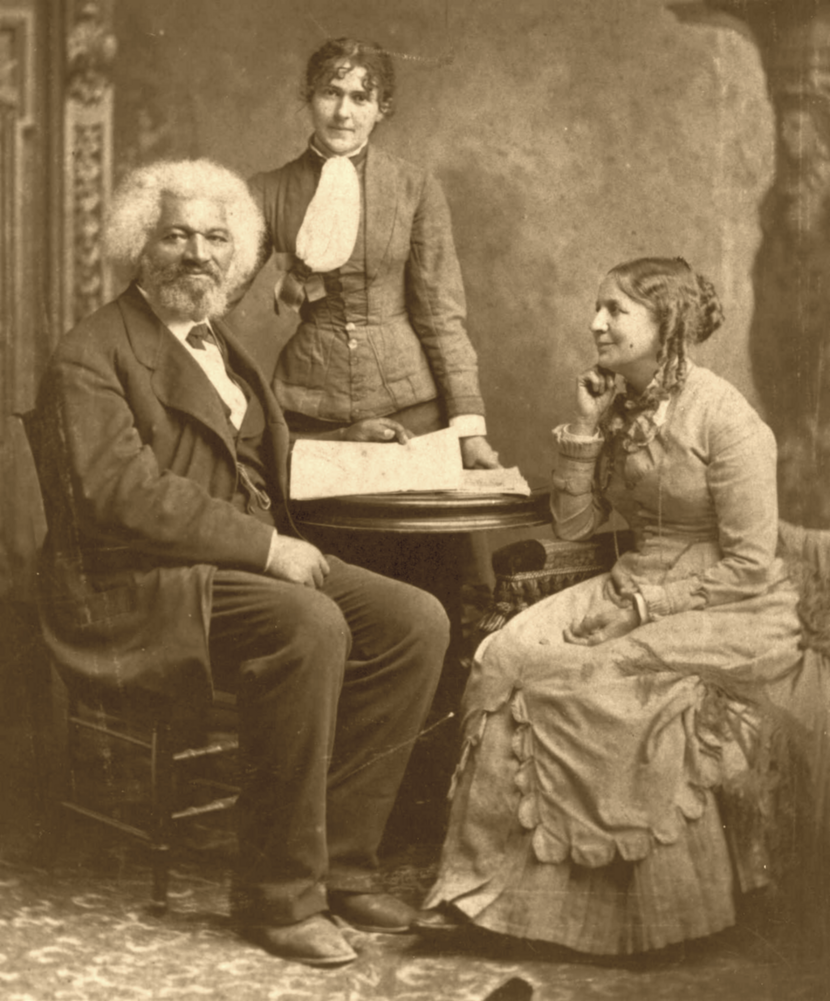

He was a women’s rights man before there were very many of them. He was the only Black abolitionist at the 1848 Seneca Falls convention. He signed the Declaration of Sentiments at Seneca Falls. He made very good friendships with most of the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement from the late 1840s right on up to the Civil War: Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and others. He will later have a terrible falling out in 1869 and ’70 with Anthony and Stanton over the fact that women were not in the Fifteenth Amendment. It was a vicious exchange between them, and most of the viciousness came from the women, and it sometimes came in racist terms.

At times he both hated and loved his own country; you can find both of those stories in Douglass’s life at different times. The Douglass of 1843, the Douglass of 1849, the Douglass of the middle of the 1850s, when he writes his second autobiography, his long-form masterpiece My Bondage and My Freedom, 440 pages of a highly political autobiography that he lands right in the middle of the slavery crisis of the 1850s. These are different Douglasses. And then the Douglasses of the midst of the Civil War, when he becomes a thumping war propagandist and an advocate of a kind of apocalyptic change in America.

Then there was the Douglass who became such an optimist about America’s future, circa 1867 to 1872, with the creation of these three great Constitutional amendments: the Reconstruction Acts, the first civil rights acts. Douglass actually believed the United States had truly reinvented itself and should be a model to the world. That is not the same Douglass you will find back in the 1840s or the ’50s. He’s not static, he doesn’t stay still as a thinker, as a writer, and even as an artist, as this writer-artist.

Douglass and self-reliance

Another paradox—or seeming paradox: he strongly believed in self-reliance, that is that Black folks should raise themselves up in every way they could, both before and after emancipation. On the other hand, he fiercely believed in using activist, interventionist government to free the slaves, to defeat the Confederacy, and to protect Black citizens—and for that matter all citizens—against terror and intimidation during and in the wake of Reconstruction.

Today we have a tendency, politically, to want to put him in a box. There are people on the right in America who want to put Douglass in that self-reliance box and say, “You see, he believed in limited government, he didn’t believe in all this activism by government.” Nonsense. He believed in both.

And why wouldn’t he? To be a Black leader in the nineteenth century, you had to believe in some degree of Black self-reliance in a society that would enslave you, possibly kill you, certainly discriminate against you, and rule you out of any kind of legal consideration. On the other hand, if you weren’t going to engage in all-out revolution, you had to somehow find a way to use government and the Constitution.

He forged a kind of hard-earned pragmatism, and I use that in the philosophical more than just the political sense. A real pragmatist, if you’ve read any William James or others of the Pragmatists, is that person who doesn’t just do what works or what’s expedient, but learns to try to sustain an open mind, who learns to try to use this until I find that that might get me to my goal. As an abolitionist, Douglass had to learn politics—although he does end up very disappointed with some political outcomes, sometimes even despair over the Republican party, of which he becomes a very active functionary in the last third of the nineteenth century.

I would also add that though one of his most famous speeches is called “The Self-Made Man”—which is a brilliant speech, a remarkable argument for the capacities of the human will (read it sometime along with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance” and see what you think)—he was not fundamentally a self-made man, as much as we want to make him that. And I think he might have been the first to tell us. There were a lot of people who helped him—a lot of women who helped him—and helped make him.

The influence of religion on Douglass

He seized upon language first and foremost through the King James Bible. I say that not as a religious point but as a historical point. Douglass learned his language in the cadences of the King James Bible. He sat, when he was 12, 13, 14 years old, in Baltimore with an old Black preacher named Charles Lawson, who was only semiliterate, but he loved the Bible and the Bible stories. And when this man found this young guy Frederick, he sat him down and they read for hours and hours out loud together, especially on Sundays, Douglass reading from the Old Testament, reading from the Hebrew prophets, and sometimes from the gospels. That’s how he gets language in his head.

The Hebrew prophets especially became personal companions to Douglass. Isaiah was his favorite, although that may be in part because the Book of Isaiah is the longest in the Bible and he used Isaiah over and over again. But he also used Jeremiah sometimes, Amos, and others; he quoted the Psalms frequently; sometimes Exodus.

The Bible was a source of language, but also of storytelling and a view of history that Douglass would keep in his repertoire the rest of his life, whatever happened to his Christian faith, which did change. He seized upon the great stories of the Bible, the wisdom in the Bible, to provide himself with a kind of language for an enduring critique of this thing called America, and of events that happened, like disunion, the coming of the war, emancipation, Reconstruction and its betrayal, and beyond.

Douglass as a “prophet”

The word “prophet” is in my biography’s subtitle, and I’ll confess that I was a little afraid of that word. That’s a big word, and I think we should all be careful whom we call a prophet. It’s not a word we should throw around too easily. To say about someone, “Oh, they were a prophet because they predicted something”—that’s not a prophet, at least not in the tradition of the Hebrew prophets or the Judeo-Christian tradition from which Douglass gathered his abilities, his power with language.

When I was working on the book, I was so afraid of this word that I actually went to some theologian friends of mine. A rabbi here in New Haven, James Ponet, was very helpful to me. He’s the one who got me reading Abraham Heschel, the great Jewish theologian of the late twentieth century. In fact, his huge volume called The Prophets was extremely valuable to me, and it’s still a companion. It’s in that book that I began to see definition after definition of what a prophet is. And it’s Heschel who said, among other things, “the prophet is human, yet he employs notes one octave too high for our ears. He experiences moments that defy our understanding. He is neither a singing saint nor moralizing poet, but an assaulter of our minds. Often his words begin to burn where our conscience ends.”

Prophets are people of words who can find the language in great crises, in turning points in history, when people are in despair or even when they’re in glee and happiness. They can find the words to help us understand what we’re going through, what it means. Douglass had that ability. You read enough Douglass—especially the speeches—and you will find him not only using passages from the Hebrew prophets, but you will read passages you want to reread, because you’ll think, “Oh my God, how did he get that? How do you see that? How did he explain secession that way?” It doesn’t mean he’s always full of wisdom and always right, but he’s capturing experience and trauma and events in language that will stay with you.

The late Donald Shriver—a great man, former president of Union Theological Seminary in New York City and a Protestant theologian, especially the Old Testament—sat me down for a three-hour lunch and gave me a bibliography, and particularly he got me reading Walter Brueggemann. What is a prophet, who were the prophets? It turns out, if somebody tells you they’re a prophet they’re not. Don’t believe them. Prophets don’t choose to be; they are chosen, by God or by history, to have a place in explaining to us who we are, what’s happening. And [through this research], I got closer and closer to a sense of safety in using the term “prophet” [for Douglass].

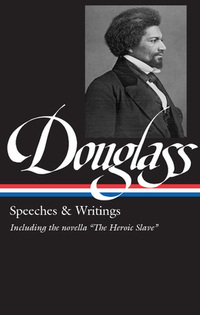

On editing Frederick Douglass: Speeches & Writings

This volume is a way of seeing many different Douglasses. I’ve spread the pieces, the essays and the speeches, over his entire life. He spent 51 years or so in the public realm, a public voice, a voice on paper and a voice in oratory. And I tried to make sure there were pieces in here that actually found his sense of humor, because sometimes Douglass, like others, had to learn ways of processing racism in humor in order to simply cope and survive.

I selected pieces that show him as a political analyst, and he was a great one, especially by the 1850s. There’s a lot in the early part of the volume where Douglass is explaining slavery, representing slavery, showing us windows into what slavery actually was; how it affected the human mind, the human body; how it was affecting the whole society; how it was affecting slaveholders themselves who were prisoners of this system.

There’s Douglass the activist, the strategic abolitionist who gets into all kinds of battles and fights with his rivals, as all radical abolitionists did, about what the best strategy should be. And he was not always right, as much as anyone else, but he was an activist advocating for methods and ways of attacking slavery, what was possible and what was not.

He’s a voice. He’s a man with a pen. He never stopped writing. He had an insatiable need to get to his desk and try to explain what he was thinking. He had that extraordinary writerly gift of hearing the music of words in his head and the ability to convert them to the page.

There’s Douglass the interpreter of events, especially when you get to the great events of the 1850s and then the Civil War itself. And by the way, in this period of the 1850s into the Civil War years, he is not inside any real political party. He’s sort of becoming a Republican, but it is not an easy place for him just yet. He’s not inside of any political circles where they’re telling him what they’re doing, he is seeing the world of the Civil War from his desk in Rochester, New York, and the many, many newspapers he read every day, every week, as he converted his analysis into his own newspaper, which he edited for 16 years, from 1847 to 1863.

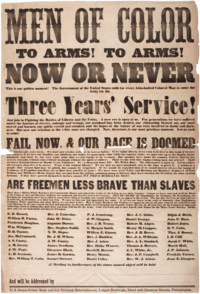

Read his speech in the middle of the war called “The Proclamation and a Negro Army,” “proclamation” meaning Emancipation Proclamation. He writes that in the month right after the Emancipation Proclamation. It’s a transformative speech that he takes on the road, gives all over the North, and it becomes the template of his speech to recruit Black soldiers into the Union Army.

Or read his 1864 masterpiece “The Mission of the War,” in which Douglass fully develops this millennialist, apocalyptic view of the meaning of the Civil War as God’s appointment, his entering of history with retribution on this deeply flawed republic to both destroy it and remake it. It’s an extraordinary speech that he took on the road and gave dozens of times in the winter of 1863–64.

And then of course the novella The Heroic Slave, his only formal work of fiction, which he wrote in 1852. It’s a sixty-page novella about a real person named Madison Washington and a slave rebellion on a ship in the domestic slave trade moving around the coast of the United States. It’s a remarkable work, and would that he had tried fiction more often, although there are those who say his autobiographies have a lot of really good fiction in them. That’s always a debate among Douglass scholars.

Douglass’s enduring legacy

Douglass is now studied by almost every discipline. There are whole books of essays by political theorists who treat Douglass as a political thinker and a Constitutional thinker. There are whole books of essays by law school professors on Douglass as a legal thinker. And there have been many, many essays and collections on Douglass as a literary figure, as a writer.

He’s a voice. He’s a man with a pen. He never stopped writing. He had an insatiable need to get to his desk and try to explain what he was thinking. He had that extraordinary writerly gift of hearing the music of words in his head and the ability to convert them to the page.

Douglass is a figure, I can confidently say, you can read forever and always see new things, new metaphors, new substance.

David W. Blight is Sterling Professor of American History at Yale University and director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition. He is the author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, winner of the Bancroft Prize, the Francis Parkman Prize, and the Pulitzer Prize. His other works include Frederick Douglass’s Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee and Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.