Long before there was BookTok, there was bibliomania, a consuming hunger among nineteenth-century American readers to amass, pore over, and cherish textual objects and commune with beloved writers via their published work.

In Book Madness: A Story of Book Collectors in America (Yale, 2022), Stanford professor Denise Gigante traces the fascinating, obsessive story of an unparalleled cultural moment where bookstores, publishing houses, and auction halls occupied the cultural center.

Praised as “a remarkable piece of book history” by Oxford University’s Seamus Perry, Book Madness cuts open the pages of an era when, to quote Gigante, “Americans became fascinated with their own history” and sought to define the nation through its art and erudition. In this interview, Library of America editorial director John Kulka speaks with Gigante about her research and the enterprising, sometimes eccentric, bibliophiles that helped inaugurate the country’s literary world.

LOA: Your new book tells a story about American bibliomania in the nineteenth century through the sale and dispersal of Charles Lamb’s library in New York in 1848, about fifteen years after Lamb’s death. How did the gin-stained, bescribbled books of a beloved English writer and antiquarian wind up in New York City?

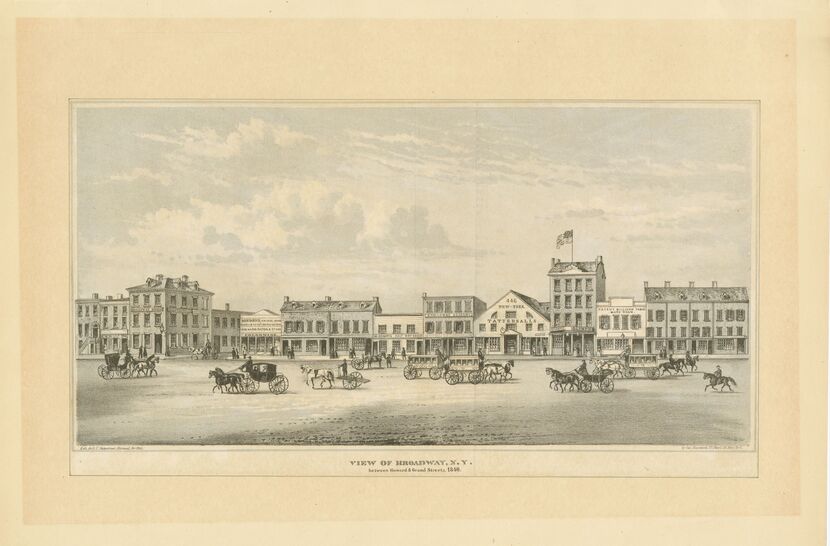

Gigante: New York, by the mid-nineteenth century, had become the book capital of America. The city was growing quickly from a commercial hub into a cultural center, and books littered the streets, literally. They spilled out from the bookstores into boxes of used books on the street. The harbor and Custom House could barely keep up with them. Up and down Broadway, there were print shops, publishing houses, auction halls, engravers who produced the illustrations for books, stationery shops, and no shortage of newsboys hawking the latest installments of Dickens’s novels.

At the bookstore of Bartlett & Welford, under the Astor Hotel on Broadway, people could drop in, sink into comfortable chairs, read, and chat with the clerks about the latest arrivals from Europe—or brush shoulders with authors, wits, and literati. James Fenimore Cooper stopped in every day, and Edgar Allan Poe came for cakes and coffee. The owners were important figures of their day. John Russell Bartlett is best remembered for his famous book of quotations, but he also catalogued John Carter Brown’s library (of Brown University) and helped the U.S. government define its border with Mexico after the Mexican–American War. His partner Charles Welford, the son of a London bookseller with a genius for bibliography, later became Charles Scribner’s business partner, importing countless books from Europe to the United States over the years.

Welford traveled back and forth across the Atlantic on the steamboat circuit in the quest for fine and antiquarian books, and when he met the publisher Edward Moxon in London on one of his trips, he discovered a hoard of bescribbled old books that Americans went crazy to get their hands on. Why? Because they had been owned by Charles Lamb, the man who wrote more lovingly about his books than anyone in the English language had ever done. They contained handwriting by Lamb and his friends, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the master of marginalia. In fact, that term—meaning the art of scribbling in the margins and blanks spaces of books—comes from Coleridge.

LOA: Is it a coincidence that bibliomania in America arose during a moment of highly charged cultural nationalism?

Gigante: The 1840s was the decade when Americans became fascinated with their own history. Historians formed state historical societies and amassed the books, manuscripts, and documents needed to write American history. This meant investigating and narrating the histories of the Americas in deep time, the histories of the British and French colonies in North America, and those of South America. It also meant tracking down and reading source materials in more than one language. All this was necessary to solidify a sense of nationhood as distinct from the Old World.

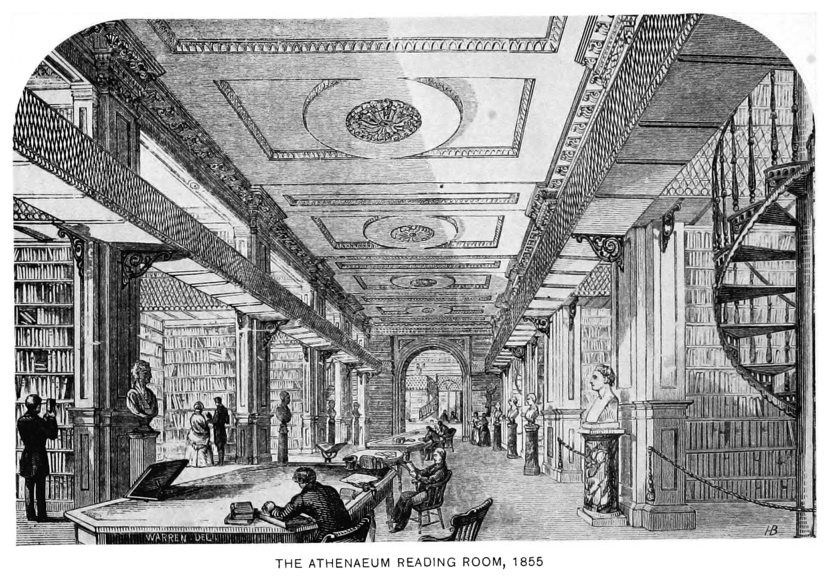

One of the stories I tell as part of the nation-making effort of that decade is the struggle to keep George Washington’s library in the country. When a bookdealer from Vermont discovered Washington’s books in the study at Mount Vernon and considered offering them to the British government for its national library at the British Museum, a group of Bostonians rose up in the old revolutionary spirit and secured the books for the Boston Athenaeum. Like Charles Lamb’s books, the books formerly owned by Washington are known as “association copies,” which, unlike more anonymous copies of a book, are unique. They bear the traces of a public or noteworthy figure, and a special aura is attached to them, making the book a sort of literary relic.

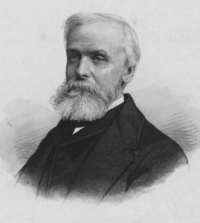

LOA: One of the bibliophiles we meet in passing is editor and publisher Evert Duyckinck, a member of the Young America movement, a close friend of Herman Melville, and publisher of the first national library of American authors—“library,” in this instance, meaning a uniform edition like the volumes in the Library of America. Duyckinck’s Library of American Books, as it was called, had only a three-year run, from 1845 to 1847. It was an idea ahead of its time. What is Duyckinck’s role in the story of bibliomania?

Gigante: Evert Augustus Duyckinck is a fascinating figure in this country’s cultural history. He worked tirelessly to promote a distinct American literary tradition in English, one that could stand up proudly and face down its parent across the sea. To this end, he cultivated the work of Hawthorne, Melville (he was among the first to read Moby-Dick in manuscript), and Poe, among others. He tried to induce Emerson to publish in his Library of American Books, telling the Sage of Concord that it was “important to the literature of the country” to have examples of writing like his in circulation, but Emerson proved impossible to corral. He recommended Thoreau instead, before Thoreau was yet in print, though both published their works in Boston.

It may be worth mentioning that Duyckinck was the son of one of New York’s first booksellers. The family had a formidable (indeed bibliomaniacal) book collection, and Duyckinck’s own tremendous energy, wit, and intelligence resulted in New York’s first review of books, The Literary World, as well as the first Cyclopaedia of American Literature, and (as you mention) the book series that was the forerunner of the Library of America. He was also an essayist who published in literary periodicals and modeled himself on Charles Lamb.

LOA: Another bibliomaniac we encounter is George Templeton Strong, known to readers as a voluminous American diarist (though in fact large portions of his diary remain unpublished). Strong was a collector not only of his own words, but also of books. What was his library like, and how does he come into the story?

Gigante: George Templeton Strong was a bibliophile as well as a collector who cared less about the rarity of his books than their content and quality, both as literature and as aesthetic objects. The son of an eminent attorney, George Washington Strong (another sign of nation-making), Strong spent much of his money in bookstores, at book auctions, and at the bookbinders. By the time of his death in 1875, he had amassed a collection to rival any in the country.

We might call Strong a “literary” bibliomaniac, and he was also a coin collector, as many American book collectors were. Like Duyckinck, he attended Columbia College when it was still in a pre–Revolutionary War building downtown, in what is now the Financial District. He enters my story as the young man who purchased all the books from Lamb’s library that contained writing by Coleridge. He signed his initials “G.T.S.” inside those books, in imitation of Coleridge’s “S.T.C.” (since Coleridge signed his own marginalia that way), and cultivated the persona of an “annotator.”

In what was then a famous essay on both sides of the Atlantic, Charles Lamb divides the human race into two species, borrowers and lenders. The essay is called “The Two Races of Men,” and Coleridge appears in it as a borrower who sometimes loses books but sometimes returns them worth more than when he took them away. Lamb puts himself in the sad species of lenders whose books, grudgingly lent, hardly ever come back. The borrowers, insofar as they are modeled on S.T.C., are morally superior. Their genius blinds them to ownership, pouring out into the margins of the books they read and, unsparingly, annotate. Lamb joked that Coleridge’s marginalia often vied favorably with the book he was annotating, not only in quality but also in quantity.

In fact, it was through the medium of these same books annotated by Coleridge that George Templeton Strong made the acquaintance of Evert Duyckinck. At Bartlett & Welford’s bookstore, Strong had copied all of Coleridge’s notes from Lamb’s books into his own books and notebooks. He was hoping to publish the notes in an edition of Coleridge’s prose for his Library of Choice Reading, a European companion series to his Library of American Books, likewise published with John Wiley and George Palmer Putnam. He requested Strong’s permission to do so, and Strong graciously replied that someone who loved Coleridge as much as he did would never keep his work from others. How Duyckinck ended up publishing those notes in The Literary World is one of the stories I tell in my book.

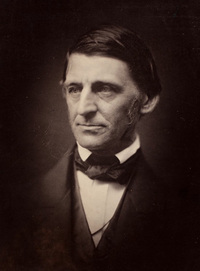

LOA: Not everyone approved of this passion for books and book collecting. Ralph Waldo Emerson spoke disparagingly of the “Third Estate”: the book-learned class who love “books, as such . . . the restorers of readings, the emendators, the bibliomaniacs of all degrees.” For Emerson, the collecting of books was an essentially antidemocratic activity. But for many nineteenth-century Americans passionate about book collecting, it was a kind of lived aesthetic. What is your takeaway from examining the bibliomania of New York Shakespeareans, Boston antiquarians, and others?

Gigante: For all that Emerson had to say against bookworms, one visit to his own impressive library in Concord, Massachusetts, will speak for itself. Thoreau may have gone to Walden Pond, but Emerson spent his weekdays in his library and his Saturdays in Boston at the bookstores, talking to publishers and literary men and seeing what was new in the world of letters. He spent his Sundays with the Bible.

Yet, it is true that Emerson was not eccentric enough, or perhaps tolerant enough, to feel at home with a genuine bibliomaniac. Bibliomaniacs were obsessive, self-directed people who lived in and through books, following their individual tastes and disregarding—or not even noticing—the supposedly world-shattering events taking place around them. Typically, their interest was in old books, and their immersion in the past—in other times and places—gave them a larger perspective at the same time as, from the outside, it would seem that they were monomaniacally focused on peculiar interests: the Puritan colony at Plymouth, Shakespeare’s plays, the publication history of the Bible, and so on.

Whatever the hobbyhorse of a bibliomaniac, you can be sure that it appealed to them more than Emersonian (or Whitmanian) democracy. You might call the Transcendentalist Emerson and his fellow Bostonians Charles Deane and George Livermore, both bibliomaniacal antiquaries in my story, as compatible as oil and water. The brilliant Livermore went to one of Emerson’s lectures and left the hall completely baffled, not knowing what he had heard or what to make of it.

LOA: Your book focuses mostly on private libraries, but toward the end of Book Madness you turn to the American dream of a Great Public Library. What is that dream and how did Americans go about building public libraries?

Gigante: Since many people did not attend school past their fourteenth year, if they got that far, college in the mid-nineteenth century was a luxury. A graduating class might consist of fifteen people. Public libraries were therefore considered necessary for the education of the people and the future of the American experiment. Education as we know it meant self-education, and it was supposed to last a lifetime.

At the time, there were different kinds of libraries serving the public, from independent libraries like the Boston Athenaeum or the Library Company of Philadelphia, to the mercantile libraries that were cropping up in the country’s urban centers; from society libraries like that of the Massachusetts or New York or Vermont historical societies, to state libraries and the national Library of Congress. But a movement began to establish major, free-access libraries that did not require an annual subscription.

The last chapter of my book focuses on Joseph Green Cogswell, a man of many talents, an educator and bibliographer. It follows him from the Harvard College Library, where he first introduced the card catalog system to America (before that, library catalogs were printed and hence less flexible), to the Astor Library, which he almost single-handedly urged into existence as the precursor to the New York Public Library. He spent years acquiring, cataloging, and shelving books purchased with the money of John Jacob Astor, the richest man in America, and his friends George Ticknor and Edward Everett followed his lead in establishing the Boston Public Library in 1848, the same year Lamb’s books were sold. Many people believed that without such libraries, American literary culture could not advance.

LOA: Where are Lamb’s “midnight darlings” today? Does his library survive?

Gigante: Alas, his legendary library was scattered. Of the sixty volumes that remained to be sold in New York in 1848, some are now in the Princeton University Library, a couple at the Beinecke Library at Yale, some at Harvard, a few in the New York Public Library, and some have been lost. Some disappeared the same year the books were sold, as buyers whose identities are unknown walked off with them. Eighteen were sold to a buyer in Cincinnati who resold them at auction later that year. Some we can trace through a few buyers to bookstores who did not keep a record of who bought them.

But their mystique remains! People are still in quest of them. Every once and a while on the internet, someone will announce that they have obtained a book from Lamb’s library with a bookplate saying, “Relics of Charles Lamb.” But caveat emptor: those are fraudulent association copies, invented by a bibliomaniac who claimed to have been descended from one of Lamb’s fictional characters and named after the essayist. The real thing, the old book Lamb loved so much that he turned to it on New Year’s Eve, calling it his “midnight darling” and wondering if he would be with it after death, haunts us like a phantom. I sometimes wonder whether those still-missing volumes have a happy story to tell after all.

Denise Gigante is the Sadie Dernham Patek Professor in the Humanities at Stanford University. In addition to Book Madness, she is the author of The Keats Brothers: The Life of John and George and Taste: A Literary History.