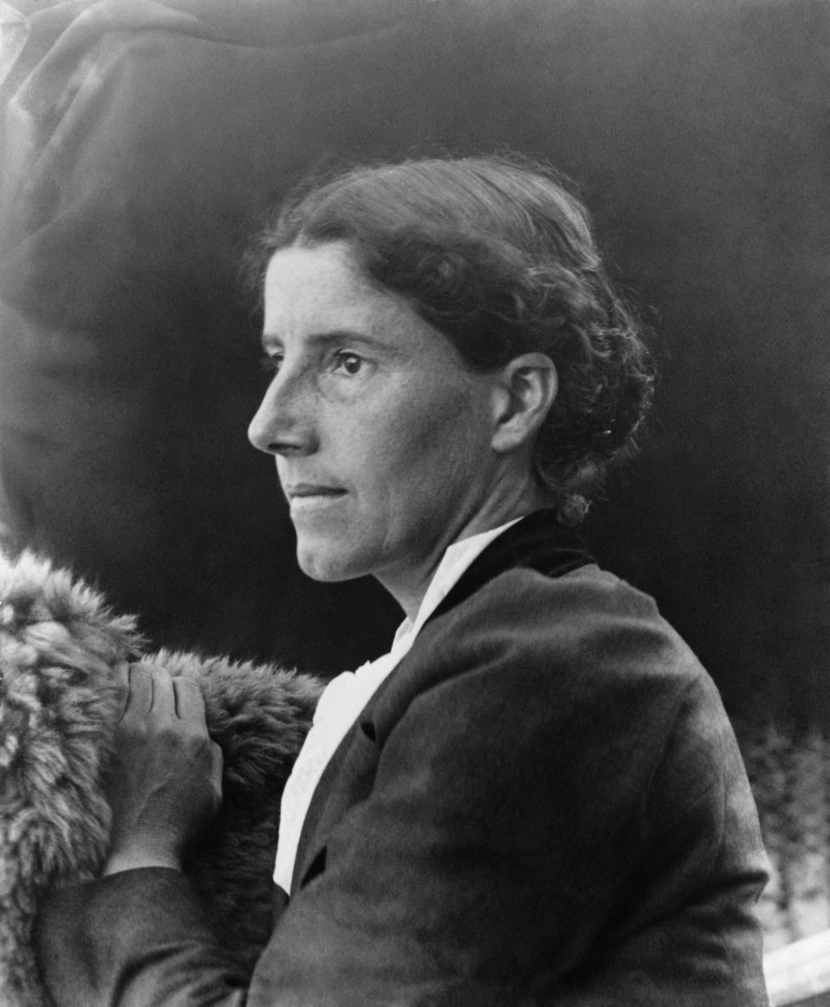

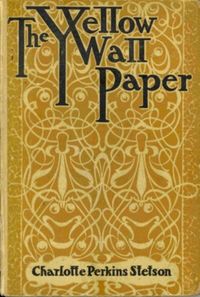

Readers may know Charlotte Perkins Gilman through “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” her widely anthologized story of a woman’s spiral into madness. But Gilman’s oeuvre extends far beyond this iconic tale of psychological unraveling. This spring, the Library of America published the fullest single-volume edition of her work ever assembled, encompassing two versions of “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” forty-four other short stories, her utopian novels Herland and With Her in Ourland, and nearly 200 poems. In this career-spanning collection, Gilman demonstrates not just a fluency in the genres of supernatural fiction, allegorical fantasy, and social realism, but also a radical willingness to engage with ideas—feminism, labor, gender relations, and societal reform—whose relevance remains undiminished today.

The LOA volume was edited by Alfred Bendixen, founder and Executive Director of the American Literature Association, whose scholarship focuses on the recovery of nineteenth-century texts, particularly by women writers, and the exploration of the role of genre in American writing.

Bendixen answered questions about Gilman’s career, literary influence, and historical significance over email.

Library of America: What will surprise readers who are familiar with Gilman only for “The Yellow Wall-Paper”?

Alfred Bendixen: Many readers may be surprised by the range and high quality of Gilman’s work. The LOA edition demonstrates the inadequacy of viewing her as a feminist who wrote one brilliant short story and a fascinating utopian novel and instead establishes her as a writer who mastered a wide variety of literary forms. Her short fiction encompasses fantasy, the Gothic, fable and allegory, and speculative fiction, as well as some powerful works of social realism that chart new possibilities for women aspiring to economic independence and personal fulfillment.

Furthermore, the volume recognizes Gilman’s achievement as probably the finest satiric poet of her time. Readers will discover a poet with a sharp intellect and a keen sense of humor who can skewer foolish prejudice and show us new ways of viewing both social issues and natural landscapes. The diversity of Gilman’s audience and poetic accomplishments may be best represented in the fact that during her life her poems were reprinted in such fundamentally different collections as Edmund C. Stedman’s An American Anthology 1787–1900 (1900), the anonymously edited A Book of American Humorous Verse (1904), Burton Stevenson’s The Home Book of Verse (1912), Upton Sinclair’s The Cry for Justice (1915), W. J. Ghent’s Socialism in Verse (1916), Emanuel Haldeman-Julius’s Poems of Evolution (1920), Louis Untermeyer’s Modern American Poetry (1921), and Catherine Miles Hill’s The World’s Great Religious Poetry (1926).

The emphasis on Gilman as a feminist thinker and social reformer has unfortunately obscured both her literary skills and her genuine commitment to artistry. Her best works show that there is no inherent conflict between the world of ideas and literary achievement.

LOA: Two versions of “The Yellow Wall-Paper” appear in the volume: the one first printed in The New England Magazine and Gilman’s original manuscript. How are they different?

Bendixen: Gilman appears to have had little control over the magazine version of the story and was surprised when it appeared in print there. The two versions share the same basic structure but there are some considerable differences, the most important of which concerns the ending. In the magazine version, the narrator ends the story by going in circles around the room. In the manuscript, she crawls over her husband’s body and presumably leaves the room. I think it is a better story if she manages to leave the room that has tormented her; it is certainly a different story.

There are other substantive changes, but the most numerous changes are in the paragraphing. It appears likely that the magazine compositors ignored the paragraph breaks in the manuscript in order to make the tale fit into the short columns of The New England Magazine. The way the narrator loses the ability to form fuller paragraphs and frame complete thoughts as she descends into madness is clear in the manuscript and obscured in the first printed edition. The differences in the paragraph breaks also shape the nuances of expression and emphasis. The presentation of both versions will offer readers a chance to explore the way minor and major shifts in detail and format affect the creation of meaning in one of the masterpieces of American fiction.

LOA: How does “The Yellow Wall-Paper” fit into Gilman’s career as a writer?

Bendixen: It is the strongest of her stories in the period following the collapse of her marriage, when she sought new purpose and new sources of income as a creative writer, essayist, and aspiring dramatist. The story was written in June 1890 but did not see print until early 1892. In between, Gilman moved to Oakland in 1891, where she immersed herself more fully in social and feminist causes and had her first experience producing a magazine, The Impress, for which she would be the chief contributor. “The Yellow Wall-Paper” remained important to her. It was one of the few short stories by any American author to be published as a standalone volume (1898), and in the last years of her life, Gilman hoped that it would be turned into a one-woman play and that Katharine Hepburn would take on the leading role.

LOA: The LOA volume also reprints a series of stories Gilman wrote in imitation of other writers. Why did she write these, and what do they tell us about Gilman as a writer? Which do you think are the most successful?

Bendixen: Gilman called these stories “the only ‘literary work’ I ever did.” In the hopes of securing subscribers to The Impress, the journal she attempted to launch in San Francisco, she produced a series of seventeen stories written in the mode of famous authors and invited readers to guess which writer was being imitated and to explain the qualities that defined that writer. The following week’s issue revealed the author being pastiched and the themes and techniques of theirs that Gilman sought to reproduce. These experiments in literary form and imitation may constitute the first creative writing course offered in the United States. The quality of these works is often surprisingly high, especially in the imitations of Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, Hamlin Garland, Henry James, Louisa May Alcott, and Maurice Maeterlinck, and Gilman’s analysis of each writer’s distinguishing features is generally acute. These stories enlarge our understanding of Gilman as a writer devoted to form and technique as well as theme and idea.

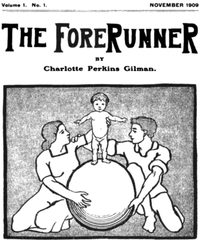

LOA: Many of the stories collected in this volume were first published in Gilman’s own magazine, The Forerunner, which she wrote and published herself. How did The Forerunner change Gilman as a writer?

Bendixen: Gilman’s entire literary life constituted a battle with the established forms of publishing in her time. Her determination to produce a magazine in which she contributed all the content was her attempt to gain control over a marketplace she found hostile or unreceptive. She hoped to be able to secure a decent livelihood through writing and have a regular outlet for her ideas which would be expressed in fiction, poetry, and essays and then—she hoped—collected into book form. The experiment was clearly not a financial success: she obtained only about half the subscribers she needed to make the venture profitable. But it freed her to devote seven years to writing the kinds of work she wanted to produce without worrying about editors and other publishers. It enabled her to focus more sharply on feminist ideas and social reform.

LOA: Herland and With Her in Ourland might be classified as speculative fiction today. The first focuses on a group of male explorers who stumble upon a utopian country entirely populated by women, while the second takes two of the central characters from the first novel on an exploration of the wider world. How have these novels influenced later writers of fantasy or science fiction, and what do they have to say to readers today?

Bendixen: There is little evidence that these works had a large impact in their own time, particularly because they were not published in book form until 1979 and 1997, respectively. Nevertheless, they have gained a significant readership as early examples of a feminist critique of American and world culture. That readership is often uncomfortable with the idea of an enclave of white women somewhere in South America who have created a civilization separate from the Indigenous populations that surround them, but also intrigued by the range of possibilities for women that Gilman imagines. These works invite us to question our own presumptions about the worlds in which we live and travel.

LOA: Gilman was known in her lifetime primarily as a poet and social critic. How has her reputation changed since then?

Bendixen: Gilman was largely forgotten from her death in 1935 until the 1970s, but she is now widely recognized as a major author as well as one of the most important feminist intellectuals of her time. The Feminist Press edition of The Yellow Wall-Paper in 1973, edited by Elaine Hedges, reintroduced contemporary readers to what is now widely regarded as Gilman’s most significant literary achievement, ultimately transforming this remarkable haunted tale into one of most anthologized and most taught stories by an American author. Ann J. Lane’s The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader (Pantheon, 1980) provided further evidence of Gilman’s literary skill in shaping feminist issues into a range of powerful fictional forms. The establishment of the Charlotte Perkins Gilman Society in 1990 offered a forum for scholars to meet and exchange ideas. Denise D. Knight and others provided new editions of her fiction and poetry. Cynthia Davis has given us the standard biography. Fans of the utopian novel have demonstrated the importance of Herland, and Gilman’s other Forerunner novels are also now available. Gilman’s place in our literary canon currently rests largely on a handful of her fictional works, though scholars continue to explore the full range of her works and ideas, and there is increasing interest in both her poetry and nonfiction.

LOA: What came as a surprise to you while putting this volume together?

Bendixen: The real surprise is that this author, who usually insisted on the didactic importance of all serious writing, successfully mastered a wide range of literary forms and demonstrated her commitment to literary artistry as well to an imaginative exploration of the world of ideas.

Alfred Bendixen is the founder of the American Literature Association, which he continues to serve as Executive Director. His most recent work includes A Companion to the American Novel (2012), The Cambridge History of American Poetry, coedited with Stephen Burt (2015), and The Centrality of Crime Fiction in American Literary Culture (2017), coedited with Olivia Carr Edenfield.