Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896)

From American Food Writing: An Anthology With Classic Recipes

After the Civil War, Harriet Beecher Stowe turned her literary attention from the abolition of slavery to the role of women in the domestic sphere. For three years during the 1860s she published a column of household advice in the pages of The Atlantic Monthly, which resulted in four of the better-selling books during her later career. In addition, she was the founding coeditor of Hearth and Home magazine. While she wrote extensively on traditional roles for homemakers (“there is nothing as sacred as . . . the time-honored institutions of hearth and home”), she advocated for suffrage, higher education, and property rights for women in the pages of her magazine.

Much of Stowe’s later fiction has been overlooked in recent decades — many readers may not realize she wrote eleven novels after Uncle Tom’s Cabin — but a notable exception is the chapter on an old-fashioned Thanksgiving celebration from the 1869 novel Oldtown Folks, which is often abridged and reprinted in anthologies. And one thing the narrator remembers most about Thanksgiving is the abundance of pie:

“The pie is an English institution,” Stowe writes, “which, planted on American soil, forthwith ran rampant and burst forth into an untold variety of genera and species. Not merely the old traditional mince pie, but . . . pumpkin pies, cranberry pies, huckleberry pies, cherry pies, green-currant pies, peach, pear, and plum pies, custard pies, apple pies, Marlborough-pudding pies—pies with top crusts and pies without—pies adorned with all sorts of fanciful flutings and architectural strips laid across and around, and otherwise varied, attested the boundless fertility of the feminine mind when once let loose in a given direction.” (Pies seem to have been a family obsession; her brother Henry Ward Beecher, a famous preacher, wrote an entire essay on apple pie.)

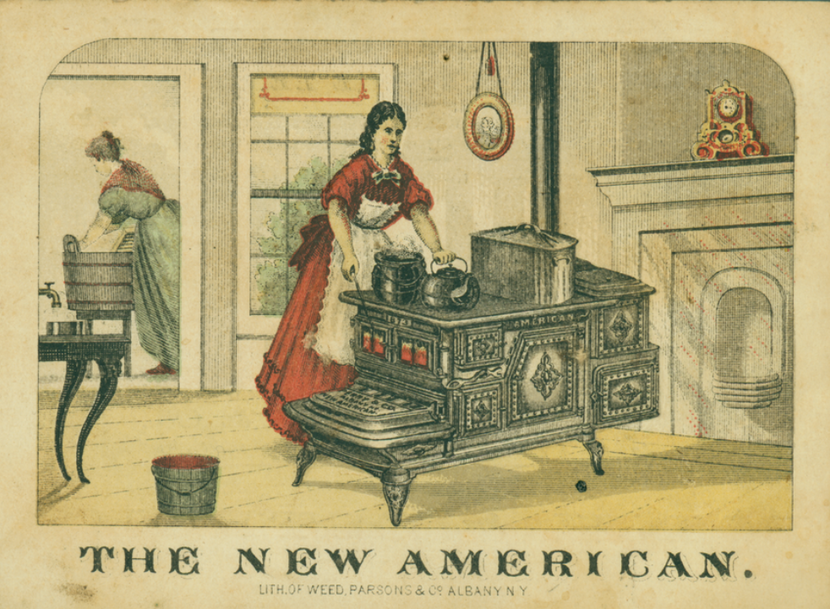

While Stowe had nothing but compliments for American pies, she had harsh words for the way her fellow countrymen and -women prepared and cooked meat, and she especially detested the new, mass-produced cooking-stoves and the American habit, born of convenience, of serving “dried meats with their most precious and nutritive juices evaporated.” She urged her readers to follow the lead of European chefs, especially of the French—advice that was, in fact, remarkably prescient.

For our Story of the Week selection, we present the section of her essay “Cookery” on the proper preparation of meat dishes, and in the introduction we explain what Christopher Crowfield had to do with all this.