Earlier this fall Library of America published the second volume of its Ray Bradbury edition: The Illustrated Man, The October Country, Other Stories, which gathers two of his most celebrated collections and twenty-seven other stories. The volume was edited by Jonathan R. Eller, the author of the definitive, three-volume Ray Bradbury biography (Becoming Ray Bradbury, Ray Bradbury Unbound, Bradbury Beyond Apollo) and the general editor of the Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury and The New Bradbury Review. He is emeritus Chancellor’s Professor of English at Indiana University and cofounder of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies, which he directed for a decade until his retirement in 2021.

The arrival of this volume in time for its originally planned publication date is due to a combination of happenstance and foresight. “I began work on the second volume just before the campus was closed in March of 2020,“ Eller told us. “On the final day before closure, I signed out the first editions of the Bradbury titles involved in preparing the volume and brought them home. The stories of Ray Bradbury, the masterful teller of tales, were with me during the planning work for this volume, and they stayed with me, close at hand, all the way through.“

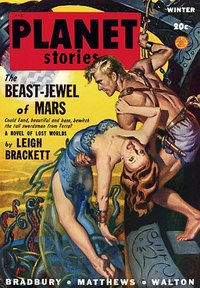

Via email, Eller answered our questions about the enduring critical and popular success of Ray Bradbury’s short fiction and how his short stories gradually moved from such pulp magazines as Weird Tales and Planet Stories to “slick” magazines like Harper’s and The Saturday Evening Post.

Library of America: This volume serves as a companion to LOA’s earlier Ray Bradbury: Novels & Story Cycles; together they collect Bradbury’s fiction of the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. How did Bradbury’s writing evolve during these early decades of his career?

Jonathan R. Eller: Throughout World War II, Ray Bradbury published in the genre pulps by way of his first New York agent, Julius Schwartz. His success with off-trail stories in the pages of Weird Tales came first, as he slowly developed a style to match his tales of strange children and eccentric supernatural creatures that bore little resemblance to the conventional vampires, ghosts, and werewolves usually featured in the supernatural pulps.

By 1945 he had found another reading audience through the crime fiction pulps, again creating unconventional characters who blurred the boundaries between rational, neurotic, and psychotic behavior. All along he had also been publishing in the science fiction magazines with limited success, hampered to some degree by an anxiety of influence and the virtual lack of any background in the sciences or technologies that stimulated many other writers in the field.

Nevertheless, Bradbury was already developing his own distinctive, metaphor-rich style, and genre mentors such as Leigh Brackett, Edmond Hamilton, and Henry Kuttner helped him discover his true strengths as a writer. Bradbury always believed that his subconscious was the key to original ideas, and by the mid-1940s he realized, on some level, that his strengths were not in imagining the experiences of others, but in telling stories that came from the emotional responses to life found in the mind of a child, and the mind of the adult that the child would become. These subjects he knew well.

By 1945 he was beginning to sell stories on his own to the major market magazines, as editors discovered the emotional power of his better stories and the essential truths about the human condition that those stories revealed. In 1947 literary agent Don Congdon signed on to represent Bradbury in all markets, and Congdon’s deep understanding of Bradbury’s creative strengths and weaknesses helped Bradbury expand to a broader literary market. Critics and reviewers continued to apply genre labels to Bradbury, but his writing rarely followed genre conventions. His use of science fiction was actually a frame or armature upon which he could place humanized stories of space travel, the dark fantastic, crime stories, and more and more of the memories of his Midwest childhood in Waukegan, Illinois.

The story cycles that he formed into The Martian Chronicles (1950) and the more fully novelized Dandelion Wine (1957) were close kin to the tales that he gathered into story collections such as Dark Carnival (1947, refashioned with substantial changes as The October Country, 1955), The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953), A Medicine for Melancholy (1959), The Machineries of Joy (1964), and I Sing the Body Electric! (1969). The short story was his true form, and, like Mark Twain, he had to develop the ability to sustain the long fiction that emerged from shorter concepts, such as “The Fireman” novella he transformed into Fahrenheit 451 (1953) and the story “The Black Ferris” that became Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962). In one form or another, the stories of his first three decades remain in print today, revealing how his masterful stories of that period helped to bring genre fiction, and especially his very special wonder-based brand of science fiction, into the literary mainstream.

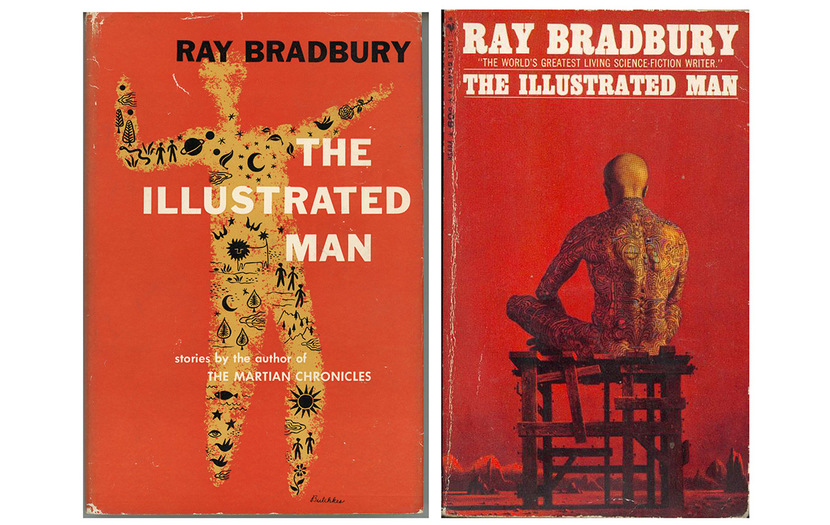

LOA: The Illustrated Man and The October Country still sell at a level unusual for story collections seven decades after their publication. What do you think accounts for their continuing popularity?

Eller: Bradbury’s natural ability to spin out poetic, metaphorical prose emerged early in his career, and the best of his stories combined this ability with tightly focused plots and timeless themes. The Illustrated Man (1951) took shape very quickly after the publication of The Martian Chronicles, providing a way to present the best of the remaining science fiction stories he had published in magazines up to that time. The suspenseful and often dark fantasies of The October Country included roughly half of the stories he had collected in Dark Carnival, all revised and a few re-written, along with four newer stories that showcased his continuing mastery of suspense.

The contents of both collections contain the hallmarks of a master storyteller, but the themes are perhaps the key to the longevity of these titles in American culture. The eerie character of the Illustrated Man only appears in the prologue/epilogue framework, but the story-telling magic of his shifting illustrations is one of the most creative devices associated with Bradbury’s legacy as a cultural icon. Within that framework, the various stories explore themes that are fundamental to the human condition, and therefore timeless in the hands of a gifted teller of tales: How do we respond to Otherness? What gives people the wisdom to leave behind intolerance and hatred? What do people take to a new world? How do they overcome loneliness and despair when they leave their home forever? And how will they deal with a completely alien environment and unimaginable forms of life?

Between the lines, The October Country offers perhaps the best example of Bradbury’s constant urge to revise and even refashion his stories. His revisions of the mid-1950s show a maturing master at work, but some readers familiar with the original versions felt that Bradbury had, in subtle ways, taken the edge out of his trademark Bradbury twist. Some readers found the older stories even better with the many small changes he made in descriptive passages. Still others, perhaps less familiar with the originals, simply found enduring tales of the supernatural reaching into the lives of everyday people.

Themes of isolation and alienation run through these unsettling stories, along with the desire for love and acceptance as Bradbury explores the borderlands between life and death. But Bradbury also placed a handful of new tales in The October Country that showed how far he had come from the supernatural stories of the 1940s. He opened the collection with “The Dwarf” (an aspiring writer with a secret) and closed it with “The Wonderful Death of Dudley Stone” (a prolific author who seems to have no secrets at all). In this way, Bradbury explored the nature of authorship, as well as the hidden traps that are always waiting to diminish and destroy creativity in any field of endeavor.

LOA: How do Bradbury’s stories compare to the novels and story cycles collected in the earlier volume? How did Bradbury think about novel writing as compared to short stories?

Eller: The novels, story cycles, and short stories brought together in these two Library of America volumes are all cut from the same creative fabric. Reading and writing were as essential to Bradbury as breathing. Ideas welled up constantly from what he called “the old subcon,” sometimes stimulated by word associations; if the idea or object fired his conscious imagination, a story draft would emerge from his typewriter within a few hours. Other ideas took time to evolve on paper.

Bradbury often worked recursively, returning to an idea or an experienced trauma that seemed to demand further attention. The mummies of Guanajuato in their Mexican catacomb petrified him with fear, and he would write a half dozen stories that revolved around that encounter. As he imagined encounters with Martian life and environments, he would write variations on stories of first contact, settlement, abandonment, and second chances for colonization. Many of these stories were revised and bridged into The Martian Chronicles, which opens volume 1, while others were gathered into volume 2’s The Illustrated Man. Bradbury’s Greentown stories, exploring memories and imaginings from his Illinois childhood, provide the story-chapters of Dandelion Wine and the setting of Something Wicked This Way Comes in volume 1. The backdrop of Greentown also informs stories of The October Country as well as subsequent collections that are represented in the “Other Stories” section of volume 2.

By 1945 Bradbury was thinking in terms of evolving novels out of certain groupings of related stories, and his productivity provided a great deal of material. His strange but fascinating tales of the supernatural Elliott family (and the adopted human child at the center of their saga) led Bradbury to shop the concept for a half-century before finally novelizing the story grouping as From the Dust Returned. It took nearly fifteen years to grow the single incident of “The Black Ferris,” where two Greentown boys discover the carnival ride that allows the proprietor to change his age at will, into Something Wicked This Way Comes. Dandelion Wine, near-cousin to a novel, represented one of the greatest creative blocks of his career. His late-life detective novel Death Is a Lonely Business (1985) grew slowly out of a 1940s detective story that was not published until after the novel reached print.

Throughout the early decades of his career, Bradbury, a master of the short story form who honed his craft without any formal education beyond high school, ran the risk of becoming one of the few acclaimed American fiction writers to fail with free-standing works of long fiction. That he did eventually succeed as a novelist was due, in part, to his ability to stand back and reshape his short fiction throughout his career. Like the animated stories revealed in the body art of his Illustrated Man, Bradbury’s stories changed shape in seamless ways, even when stretched to fit the fabric of novel-length fiction.

LOA: The stories in this volume are not just science fiction, for which Bradbury is best known, but also the macabre, horror, and even fantasy. Can you talk about the genres Bradbury wrote in?

Eller: With the exception of some of his earliest stories, written for a pulp market where even experienced writers earned only a penny a word, Bradbury generally avoided the kind of slanting required to meet the genre expectations of editors and publishers. His editors at Weird Tales wanted conventional weirds involving traditional concepts of supernatural creatures, but they continued to buy Bradbury’s tales because they were well-written, unfailingly suspenseful, and attracted a wide readership. Some of the detective fiction editors despaired at the slim prospects of Bradbury ever writing a rationally plotted crime tale, but again readers (and more than a few of the genre editors) enjoyed the edginess and emotional impact of his off-trail crime-suspense stories of the 1940s.

By the 1950s, as Bradbury became one of the most recognized names in science fiction at home and abroad, it was sometimes suggested that Bradbury never really wrote science fiction at all. His brand of science fiction privileged a sense of wonderment in the achievements required to reach other worlds, and he often tried to imagine the kind of people we would have to become as we journeyed out to the stars. His science fiction was not genre-specific in any sense. Like a few of his peers, most notably Clifford Simak and Theodore Sturgeon, he was interested in the human factor, and how humans would ultimately use the wonders of our technologically driven age.

LOA: Do you have a favorite among the stories in this volume? Are there any lesser-known selections in this volume that you think deserve renewed attention from critics and fans?

Eller: The saying goes that everybody knows a Ray Bradbury story, but there are stories presented in this new volume that are underappreciated. The best example is probably “Asleep in Armageddon,” a 1940s tale that blends pure terror and isolation with an effective science fiction setting. “The Strawberry Window” is another hidden gem that considers how settlers on new worlds might lessen the loneliness of an alien environment where they must spend the rest of their lives.

My favorite story in the collection is found in the “Other Stories” section—“The Golden Apples of the Sun,” first published in 1953. I discovered this story in 1962, and I marveled at the idea of a mission to the sun that would scoop up a mass of solar fusion and return to warm Earth’s cities with the impossible gift of a controllable fusion reaction. Fusion provided the unimaginable explosive energy of the hydrogen bomb, and here was Ray Bradbury telling us that it just might be possible to imagine a good purpose to this nightmare marvel of modern physics.

“The Golden Apples of the Sun” was probably the most audacious example of Bradbury’s un-scientific science fiction, but it mesmerized me. Over the years, as I came to know Ray Bradbury and write about him, I realized that I had not been alone in my reaction to this story. I would meet and read about many participants in space age achievements who were inspired in part by Ray Bradbury’s fiction to become astronomers, astrophysicists, planetary scientists, aerospace engineers, and astronauts. Some of these people would cite “The Golden Apples of the Sun,” as far as it is from anything remotely resembling science fact, as the story that got them interested in outer space. In my lifetime Ray Bradbury’s dreams of the space age became our dreams as well, and for me, it all began with this story.