H. L. Mencken (1880–1956)

From H. L. Mencken: Prejudices: The Complete Series

“The secret of Mencken’s ability to get away with needling the American public was probably that he loved being amused by his country’s vulgarity as much as he deplored it,” Phillip Lopate wrote when he included Mencken’s classic essay, “The Hills of Zion,” in the recent anthology “The Glorious American Essay.” To say he “got away with” it is something of an understatement; a century ago, he was perhaps the most-read newspaper columnist in the nation; by 1926, after Mencken’s star turn at the Scopes trial, Walter Lippmann extolled him as “the most powerful personal influence on this whole generation of educated people.”

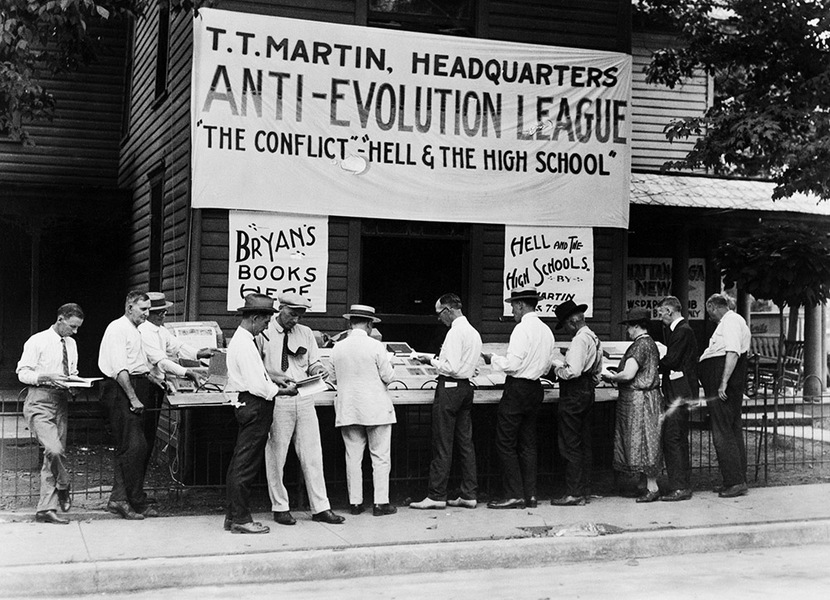

His diatribes against the South provincialism caused one Florida paper to call him “the most universally hated man in the United States,” yet the columns he wrote and the magazines he edited were read just as widely south of the Maxon-Dixon line. Younger writers from the South, such as the novelist Thomas Wolfe and the playwright Paul Green, idolized him; a teenager named Richard Wright encountered his essays and was thunderstruck, “He was using words as a weapon, using them as one would use a club. . . . What amazed me was not what he said, but how on earth anybody had the courage to say it.” When he went to Dayton, Tennessee to report on the Scopes Trial,” the owner of the town pharmacy, which sold The American Mercury in its newsstand, rushed outside to greet its famous editor; a newspaper mockingly reported that Mencken had “emotional convulsions” when one resident announced herself a fan. “He calls you a swine, and an imbecile, and he increases your will to live,” wrote Lippman.

The columns Mencken wrote in Dayton, fueled in no small part by his disdain for anti-evolution crusader William Jennings Bryan, would ultimately shock the town; he left before the trial ended on his own volition—he had a magazine to publish, after all—yet rumors quickly circulated that he fled the area because he was going to be tarred and feathered. Mencken’s cynicism upended the town’s boosterism during the trial and turned the place into a laughingstock: as the late Terry Teachout remarks, “he left his mark on the town of Dayton and the corpse of Bryan, and it remains there to this day.”