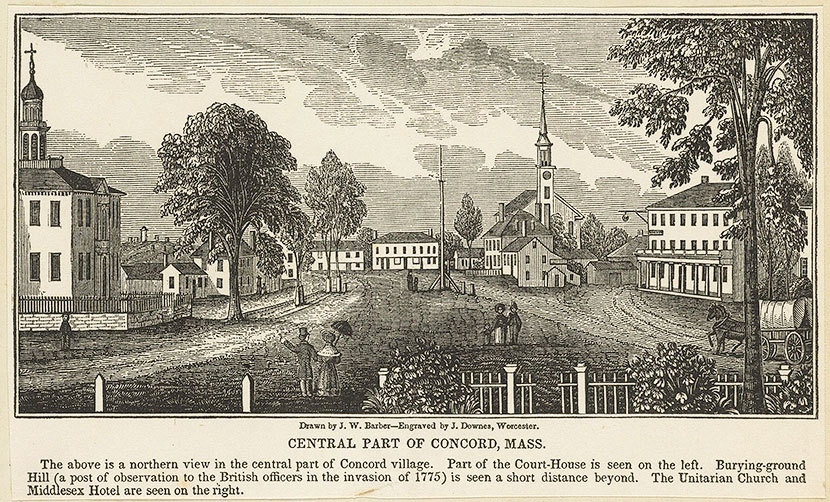

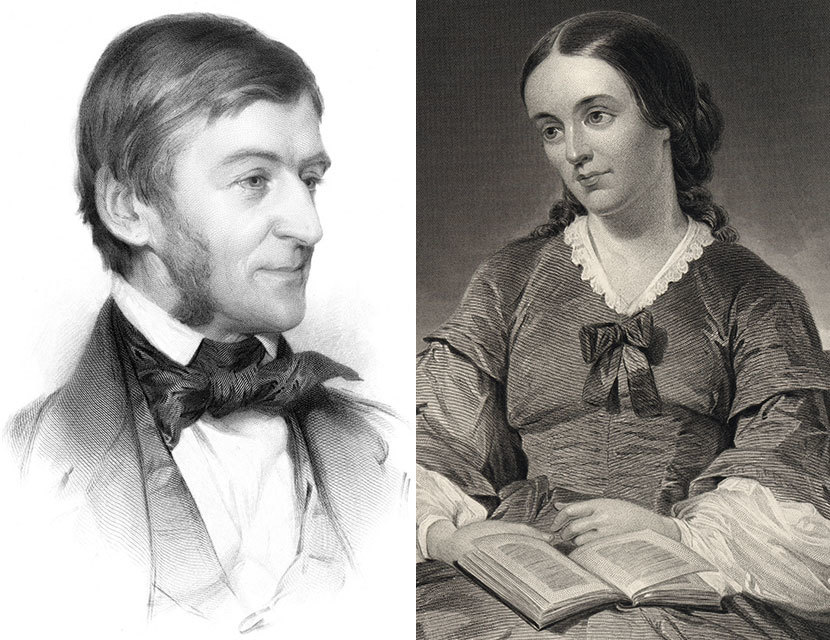

Calculated on a per capita basis, at least, few places can rival Concord, Massachusetts, as a center of gravity in American history and letters. With a population of just two thousand for much of the nation’s first century, it was not only the site of the famous first battle of the American Revolution, but it was also the home of Library of America authors Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Louisa May Alcott (and of Margaret Fuller, who will soon join the series), as well as a crucial creative waystation for yet another LOA writer, Nathaniel Hawthorne. If there was such a thing as an American Renaissance, then Concord surely was its Florence.

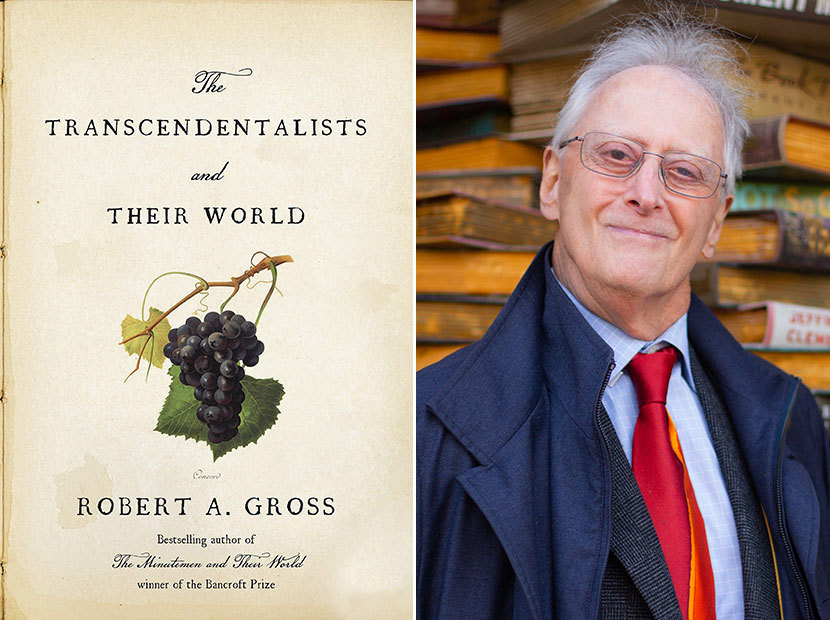

But why? How did this staid shire town become the seedbed and proving ground of Transcendentalism? And how was this radically new American philosophy shaped by the specific locale from which it arose? These questions lie at the heart of Robert A. Gross’s monumental new book, The Transcendentalists and Their World, published last fall by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and coming in paperback in November. A sequel, of sorts, to Gross’s 1976 book The Minutemen and Their World, which won the prestigious Bancroft Prize and which will be rereleased in a revised and expanded edition in November, The Transcendentalists and Their World carries the story forward to the first decades of the nineteenth century, showing us with unprecedented clarity how community life in Concord—encompassing everything from agricultural reform and theological discord to abolitionism and the coming of the railroad—entered powerfully into the works of its most famous writers.

Gross’s new book has been decades in the making. Named one of the ten best books of 2021 by the Wall Street Journal, it has been hailed as “a Hope Diamond of history-writing” by Gordan S. Wood, “a brilliant successor to that little gem, The Minutemen and Their World. Although much larger and richer,” Wood writes, “this story of Concord in the age of Emerson and Thoreau has the same social and cultural wholeness, the same easy, readable prose, and the same reverberating significance as the earlier book. Well worth waiting for, it is surely the most complete history of an early American town ever written.”

We are grateful to Professor Gross, the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Professor of Early American History Emeritus at the University of Connecticut, for sitting down with us from his home in Concord for a few questions about his new book and the prodigious research behind it.

Library of America: First off, congratulations of the book and on the reception it has received. “Hope Diamond” strikes us as high praise indeed, and fittingly so. The book’s first half, which lays the ground for the advent of Transcendentalism in its second half, is a masterclass in social history: eight chapters on different aspects of Concord’s development in the early nineteenth century that give vivid new life to such shopworn and sometimes nebulous historical concepts as the market revolution, the feminization of the churches, and the rise of Jacksonian democracy. Why was it important to start a book about Emerson and Thoreau in this way?

Robert Gross: Emerson and Thoreau were speaking to and about a society undergoing rapid change. But those changes didn’t start when Emerson showed up on the scene in fall 1834. The social transformation began well before then, with a gathering momentum during the very years when Thoreau, born in Concord in 1817, was growing up, attending school, and entering Harvard College, before returning to his native town at the end of August 1837. Over this period Concord was dramatically unsettled by the expansive forces of capitalism and democracy. Although, as you note, its population numbered little more than two thousand souls, the town was increasingly integrated into metropolitan, regional, and national markets. It experienced its own agricultural and industrial revolutions. It also became religiously diverse, politically polarized, geographically mobile, economically unequal, and segmented into enclaves of neighborhood, class, and race, all developments I trace in detail in the book.

These developments were peaking in the very years that Emerson was settling into town and Thoreau embarking on adult life, taking a small, ordered society, founded by Puritans and defended by Minutemen, and unsettling it with new principles of social action. The older Concord emphasized hierarchy, homogeneity, and consensus. It rested on inherited institutions and involuntary associations. The emerging society put a priority on autonomy and choice. Instead of deferring to authority and tradition, the townspeople pressed the right of individuals to act on their own judgment and for their own gain.

It was this erosion of communalism and the assertion of the individual that Emerson perceived as the driving force of the age. “The former men acted and spoke under the thought that a shining social prosperity was the aim of men, and compromised ever the individuals to the nation,” he announced in 1837. “The modern mind teaches (in extremes) that the nation exists for the individual, for the guardianship and education of every man.” His lectures from 1837 to 1842 laid out the character of the new age, and they were shaped by what he heard and saw in the town. I thus wanted in Part One of the book to give the reader a palpable sense of what the old order of Concord had been like, how it still lingered as Emerson came to settle in Concord, and how it was coming undone by the voluntary choices of the inhabitants themselves, even as they looked for fresh ways to make sense of the unexpected world they were bringing into being.

LOA: In this first section we come to know a large cast of characters from every corner of Concord, including Black families struggling on the community’s margins. But one figure stands out especially: the Reverend Ezra Ripley, who, having succeeded to the pulpit of Concord’s First Church on the death of Rev. William Emerson, the Transcendentalist’s grandfather, during the Revolution, remained in office for an astonishing 63 years, functioning as a kind of living bridge between your two books. Did Ripley’s lengthy tenure serve to mask some of the deeper changes in Concord over the period, or in some sense cast a spotlight on them? How much did his remarkable longevity contribute to the Transcendentalist critique of the hidebound?

Gross: That’s an insightful take on the role of Ezra Ripley in Concord’s history. But let me say first that I presented such a large cast of characters for several reasons. I wanted to write as inclusive an account of Concord as possible, from the bottom up, the top down, and the middle out. This has been the social historian’s dream, and the astonishingly rich documentary record of Concord from the first half of the nineteenth century promised to realize it. So, I took up the challenge of telling the story from multiple viewpoints (and leaving a lot of my research on the cutting-room floor!) and introducing into the narrative various individuals who would eventually either come into contact with Emerson and Thoreau in Part Two of the book or bear upon the intellectuals’ assessments of the local scene. Previous biographies and literary histories have viewed the townspeople through the eyes of the famous writers, whose journals and letters are replete with observations of the neighbors and notes of conversations with them. I wanted to free them from the Transcendentalists’ gaze, to go beyond large generalizations about social change and to recover and convey the lived experiences of the inhabitants, to show how individuals made choices in their lives, within the historical circumstances they were given, broke with older practices or adopted novel ones – and unwittingly, gave rise to a new way of life.

Ezra Ripley—“Doctor Ripley,” as he was known after Harvard granted him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree in 1816—is a prime example of a figure striving to sustain the old order and undermining it in the process. Ordained in 1778 as the established minister of the town, whose salary was funded by the taxpayers, Ripley took the entire community as his parish. “My people,” he called them with proprietary pride. In some 2,500 sermons over six decades he discoursed on the duty of his parishioners to one another, to the Commonwealth, and to God. In the gospel according to Ripley, the fundamental value was community. “Who could live alone and independent?” he once asked the congregation. “Who but some disgusted hermit or half crazy enthusiast will say to society, I have no need of thee; I am under no obligation to my fellow-men?” Just the opposite was the case: “Every member of the community is obliged to seek and promote the public good.”

Ripley infused this social ethic into his every activity. It informed the rules he composed to govern the Concord schools. It inspired his vision of Freemasonry as a “handmaid” to Christianity in promoting “benevolence and charity.” It lay behind his progressive support for female education and his approval of the Concord Female Charitable Society in 1814 as a medium of female initiative. It drove his determination to bring everyone in Concord within the fold of the church. Ezra Ripley was no hidebound defender of the status quo.

Yet, the minister undercut the unity he tried so long and hard to sustain. Ripley added to the social complexity of the town by playing a key role in launching several voluntary associations. In pre-Revolutionary Concord, a quintet of public institutions—town meeting and militia, established church and town schools, plus taverns (licensed as “public houses”)—was sufficient to organize collective life. With Ripley’s endorsement, Concord added one organization after another for the sake of moral and cultural improvement. The diversification of the town had an unintended consequence. The townspeople withdrew into clubs of the like-minded and pulled apart from others.

Finally, Ripley provoked a schism in his church through his very efforts to open the meetinghouse doors and bring everybody in. He liberalized admission requirements, relaxed the obligations of membership, and concentrated on bringing the community together on the Sabbath. He thereby forfeited the support of many who clung to traditional theology and yearned for greater spiritual intensity in their worship, including Henry Thoreau’s aunts, Elizabeth, Jane, and Maria Thoreau, who finally lost patience with Ripley’s dry sermons and led a little band of dissenters out of the First Parish and into a Calvinist communion of their own. The New England ideal of one town, one church, gave way to demands for individual choice.

Even as Doctor Ripley contributed to the rise of this more competitive and pluralistic society, with greater freedom for the individual, he had little to offer his people to make sense of the social upheaval. In 1837, approaching age 85, the parson came before the Concord Lyceum to present a diagnosis of “the agitated and unsettled state of society.” The symptoms were alarming: “bitter contention and discord among brethren . . . and the destruction of mutual confidence and harmony among the people.” In a complaint still common today, the patriarch bewailed the loss of community. Neighbors used to know one another, share mutual interests, respect one another’s views. Now, with so little in common, they exaggerated their differences and polarized the community. This was a clear description of the widening distances between the townspeople, but with no acknowledgment that the inhabitants had been unraveling the threads of community for over a half-century, all the while under his own steady guidance. His only answer was to invoke the mantra of “interdependence” and urge his people to sacrifice for the common good.

In his last two decades in the pulpit, Doctor Ripley, with his gray wig, white neck stock, small clothes, long stockings, knee buckles, and calf-length coat, embodied the old order of the eighteenth century. He was, as you suggest, a living link to the Revolutionary generation, whose legacy he labored tirelessly to memorialize on the landscape, finally donating the land to the town on which to erect an obelisk on the site of the battle of April 19, 1775. For just this reason, he represented for his Transcendentalist grandson the dead hand of the past weighing down the rising generation. “Our age is retrospective,” Emerson complained in the very first sentence of Nature (1836), which he began to compose under the very roof of the Manse. “It builds the sepulchres of the fathers . . . The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we enjoy an original relation to the universe?” In July 1838, on the eve of his excoriation of the Unitarian clergy in his famous address to the Harvard Divinity School, he could not contain his impatience. “Do let the new generation speak the truth,” he confided to his journal, “& let our grandfathers die.”

With no faith and no philosophy to justify the new freedom of the individual, Doctor Ripley left an opening for his Transcendentalist step-grandson to step in.

LOA: After observing that “the Sentiment of Religion is at this time perhaps more potent and prevailing in New-England, than in any other portion of the Christian world,” John Quincy Adams noted in his diary entry for August 2, 1840, that “a crack-brained young man named Ralph Waldo Emerson, a son of my once loved friend, William Emerson, and a Class-mate of my lamented son George, after failing in the every day avocations of a Unitarian preacher . . . starts a new doctrine of transcendentalism, declares all the old revelations superannuated and worn out, and announces the approach of new Revelations and prophesies.” For Adams, these “wild and visionary phantasies,” this “hurly burly,” signified nothing more than “the restless and reckless pursuit of mere innovation.” Despite his lifelong interest in philosophy, Adams was clearly unable to take Emerson seriously, an example, perhaps, of the generational dimension of Transcendentalism. Is it helpful to think of Transcendentalism a youth movement? And if it is, does that account for the enduring appeal of Emerson and Thoreau’s writings, which most of us encounter first in school?

Gross: I wish that I had seen Adams’s dismissal of Transcendentalism before sending my book to press. I would definitely have included it! His negative view was of a piece with Ezra Ripley’s disdain for “our modern speculators,” whose Transcendentalist heresies were infecting his own family circle. Waldo Emerson was not the only misguided kinsman. George Ripley, the founder of Brook Farm, was the parson’s first cousin once removed and a frequent visitor at the Manse. He had prepared for admission to Harvard under the tutelage of Rev. Samuel Ripley, the Concord minister’s son. Even more alarming, Samuel’s wife, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, appeared open to the new ideas, and her brother, George, embraced religious radicalism, became a close friend of Waldo Emerson, and joined Brook Farm. Despite these close connections, the Concord minister could not fathom the appeal of Transcendentalism. Its religious speculations lacked “common sense”; its social sympathies were too thin. Instead of promoting “charity and benevolence,” the new movement focused single-mindedly on individual growth. It was selfish, at heart. Ripley even coined a term for the disposition that Emerson was advocating and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America was popularizing as “individualism.” To the old man, the adherents of the new philosophy were “Egomites,” claiming “a divine mission” on which they “sent themselves.”

The history of New England religion and thought, Perry Miller once observed, could be told as a narrative “from [Jonathan] Edwards to Emerson.” Seen from Concord, the passage might be more accurately portrayed as a sequence from Peter Bulkeley, the founding Puritan minister of the town, to William Emerson, the Patriot preacher of the Revolution, to Ezra Ripley and thence to Emerson.

Waldo Emerson was glad to consign his grandsire to the dustbin of history and hail the advent of a new generation. As a public speaker, he targeted the young as his special constituency. Over the course of four decades as an itinerant lecturer, from 1837 to 1879, he delivered nearly three dozen discourses at liberal arts institutions extending from New England to the Midwest. In these talks he pled the case of alienated youth, upholding their ideals and sympathizing with their discontent in far-ranging criticism of an uncongenial adult world. In the process, he linked his ambitions as a lecturer to the unmet aspirations of his listeners. Together, they would form the party of the future.

Emerson’s best-known speech, “The American Scholar” address he delivered to Phi Beta Kappa during Harvard’s Commencement in August 1837, set forth the complaints of the young men in the audience, just graduating from college and on the cusp of careers. For the most part, their formal education had been misbegotten. The parents and teachers of the young took a narrow, instrumental view of schooling. It was designed for practical ends: “we aim to make accountants, attorneys, and engineers,” as Emerson had deplored in an earlier talk. But what about the “young men of fairest promise”—the best and the brightest of their time—who longed to realize their genius for the betterment of all? Harvard College had failed them. It had isolated its teenage charges in classrooms and libraries, apart from nature and from a society in ferment. Now, as the graduates beheld the prospects before them, they shrank back, no longer “in the state of mind of their fathers,” but uncertain what path to forge of their own. One thing was certain: they felt only revulsion at “the principles on which business is managed.” In despair at the gap between the vital promise and the sordid reality of the republic. Now beset by the Panic of 1837 and an ensuing depression, these idealists abandoned hope, “turn[ed] drudges, or die[d] of disgust, some of them suicides.”

Some five years later Emerson was still hailing the youth who marched to the beat of a different drummer. In his essay on “The Transcendentalist” (1843) he pictured an alienated young man very much like Henry David Thoreau, the protégé who had only recently been living in his household. Such dissidents were so put off by the shallowness and selfishness, the dishonesty and insincerity of everyday life that they could not bring themselves to join in the work of the world. Better to retreat into solitude, “ramble in the country,” and wait for something worthy of their talents and ambitions. If these nonconformists were neither “good citizens” nor “good members of society,” if they declined to vote, if they did not willingly contribute to charities and benevolent causes, so be it. Emerson had confidence that eventually “the good and the wise” would find their purpose and save the world “by speaking for thoughts and principles not marketable or perishable.” The Transcendentalists would be a prophetic minority.

Crucially, Emerson spoke to young women as well as men, even if his pronouns were masculine and his examples of self-reliance invariably male. He drew a female following to his lectures in Boston and Cambridge. A popular story made the rounds in the capital in the 1830s that a gentleman distinguished for “learning and ability” complained of his inability to comprehend Emerson’s lectures. But, he added with chagrin, “his daughters could.” The befuddled father could not miss the enthusiasm with which young women greeted the lecturer’s proclamation that each person—female as well as male, Black as well as white—had a spark of divinity within the self and that it was the noblest mission and duty of existence to ignite it into incandescence.

Emerson, of course, shared this vision with Margaret Fuller, who did far more to bring the Transcendentalist vision, with its radical potential to unsettle the rigid gender roles of the day, to aspiring women in the “Conversations” she held in Cambridge and Boston and in her foundational feminist work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century (1845). His lectures encouraged the ongoing expansion of female horizons at academies and seminaries, in new places of employment in schoolhouses and factories, and in movements for abolitionism and social reform. However reluctantly, Emerson would give in, time and again, to pressure from female relatives and friends to lend his voice to collective protests against injustice and for women’s right to vote.

Such young men and women in Emerson’s and Thoreau’s Concord anticipated the generations to follow, who, as you rightly suggest, would entertain their own misgivings about the capitalist society they were being educated to serve, about the conformity and materialism of their age and about the sacrifice of principles and aspirations that conventional careers inflicted. In my experience as a college professor, teaching seminars at Amherst College, the College of William and Mary, and the University of Connecticut, Emerson never fails to evoke a powerful response from students who encounter his appeals to the “young men [and women] of fairest promise,” with its urgent message to be true to their deepest selves and their highest ideals. “The American Scholar” address always makes for exciting seminars. And then the students move on, setting aside the hopes of youth and adapting to the demands of families and careers—though not forgetting their ideals altogether.

LOA: Just as there was an underlying irony in your first Concord book—the Revolution, you show, was embraced by the town not as a catalyst of change but as a means of reclaiming and revitalizing its communitarian origins—there is something delicious here about so comprehensively expounding the local and historical roots of a movement dedicated to, perhaps more than anything else, liberating the individual from the constraints of the past, of the traditional and the customary. Did anything like this notion sustain you over the many years you spent immersed in the raw material of social history—deeds, diaries, tax lists, voter rolls, library records, probate files, and scores and scores of newspaper reels—to produce this book?

Gross: You’ve gotten my purpose precisely! I loved the paradox—or should we say oxymoron?—of writing a social history of individualism and of rooting in history and society a movement that aimed to free people from the dead hand of the past, the iron grip of institutions, and the ferocious intolerance of the mob. “I love mankind,” Thoreau quipped. “I hate the institutions of their forefathers.” The Transcendentalists were universalist in their appeal to human nature; as they saw it, when people throw off unthinking conformity to custom and convention, when they cast aside ambitions for wealth, status, and power, they will be able to heed the still, small voice of conscience stirring deep within the self. Such a perspective is antithetical to the social historian’s ambition to connect ideas and actions to determining social forces and to the control, in particular, of race, class, and gender, not to mention region and religion. But the dream of liberating the individual from all social constraints was itself a historical project, growing out of the changing circumstances of life in New England in the 1830s and 1840s, and it calls for exploration and explanation by the historian.

In another sense, I aimed to be true to the Transcendentalist vision of democratic equality, founded on an elevation of the individual and a conviction that each of us is something new under the sun, sharing in a common divinity and infinite perfectibility. I did so by seeking to recover the stories of the various people who lived through the same changes as did Emerson and Thoreau and who made decisions about their lives as best they could. Thoreau decried the “quiet desperation” to which “the mass” of men succumbed, yet he also vowed to “live deliberately,” to treat every act of his life as a conscious choice. And, indeed, as we’ve discussed, the era I treat was one of multiplying and unprecedented choices, even as the people who lived through it rightly feared that the doors of opportunity were closing almost as fast as they were opening up – and no one more so than the free people of color in Concord and Massachusetts, who enjoyed greater integration into the community from the 1820s on, at the same time as the forces of white racism and the Slave Power encroached steadily into their lives. My aim was to tell all their stories as richly and powerfully as possible, providing the raw material and contexts for the Transcendentalists’ works.

LOA: At the opening of Walden Thoreau writes that “I have travelled a good deal in Concord and every where, in shops, and offices, and fields, the inhabitants have appeared to me to doing penance in a thousand remarkable ways.” You, too, have traveled a good deal in Thoreau’s Concord over your career. Has that passage taken on new meaning for you in the wake of your work on the town? And what of Concord today? What might Thoreau make of his town and his pond as a tourist mecca?

Gross: Thoreau grew up and came of age at an auspicious moment for the small towns of Massachusetts. The first phase of the Industrial Revolution, built on water power, spurred production and commerce, increased wealth, and integrated small towns more tightly than ever into metropolitan, regional, and national markets. For a brief moment, it was an Age of Villages, in which a community like Concord could hope to flourish as a modern center of economic, social, and intellectual life. In contrast to the Minutemen, who resisted the incursions of the British Empire into the town and defended a traditional way of life imploding from within, the people in Emerson’s and Thoreau’s Concord welcomed the agents of progress. Little did they realize that Concord would be reduced from town into suburb, especially after the coming of the railroad in 1844 and the ascendance of steam power, and harnessed to the imperatives of the ever-expanding metropolis.

But that’s not the whole story. The Transcendentalists and Their World also shows how the people of Concord strived to adapt their older ethic of interdependence to a society founded on individual freedom. To be sure, the townspeople did at times succumb to moments of fear, even paranoia, about supposed threats—Anti-Masonry in the mid-1830s, nativism and the Know Nothing Party in the mid-1850s. But a persistent and pressing theme was the continuing effort to heal divisions, reach out to newcomers, and rebuild community. The townspeople updated and sustained Ezra Ripley’s ethic of interdependence.

Even the individualist Thoreau incorporated that intellectual inheritance into his idea of ecology, stressing the interconnection of humans with all living things. So, too, in his rationale for civil disobedience, did he maintain that in our conduct of life, each of us must take care to avoid “sitting upon” other people’s shoulders. In that dictum the “Hermit of Walden” acknowledged his entanglement with his neighbors, and over the course of his antislavery activism, he continued to thicken that web. “To act collectively,” he affirmed, is in accord with “the spirit of our institutions,” and in that belief he came up with innovative ideas for public forests to preserve wilderness and taxpayer support for education and culture.

Concord is vastly different today than in Emerson’s and Thoreau’s time. Its population is upwards of 18,000, some eight times that in 1850. It’s more diverse racially, with whites now comprising 80 percent of the town, followed by people of Asian origins (8 percent), Hispanic/Latin antecedents (7 percent), and African descent (4 percent). Religious pluralism is richer than ever, though the historical Unitarian and Trinitarian churches still loom large in the town center. On the other hand, Concord today is a wealthy, upper-middle class suburb of Boston, with a good many corporate executives, especially in the fields of finance and high tech. The working people of Emerson’s and Thoreau’s time are fewer than ever, though agriculture remains vigorous on half a dozen farms.

The heritage of the Transcendentalists is surprisingly strong. A good many people take pride in the town’s twin revolutions—the Minutemen and the Transcendentalists—and identify deeply with the environmentalist legacy of Thoreau. The nineteenth-century also bequeathed a commitment to an informed citizenry in an open-minded democracy, sustained by well-funded schools, libraries, and museums. The local landscape is testimony to such commitments. Yet, the historical commission fights to save the architectural inheritance of the past from the wrecker’s ball, while the town struggles to reconcile historic preservation with demands for affordable housing. In these debates, citizens on opposing sides often claim the mantle of Emerson and Thoreau.

While I researched The Transcendentalists and Their World over four decades, my wife Ann and I moved to Concord in 2014, and I wrote the bulk of book in two drafts from 2015 to 2020. This period encompasses the tumultuous era from one presidential election (2016) to another (2020), with the many shocks to our democracy generated by the Trump administration. The inflamed politics of the time, with Americans ever-more entrenched in polarized camps, did bring to mind the conflicts of the Jacksonian era. So, too, did the strident libertarianism and anti-government sentiment espoused by opponents of Covid-shutdowns and vaccination mandates. Concord itself has been largely immune to these divisions. Politically, the town is overwhelmingly “blue.” Its support of Democratic candidates—80 percent in favor—is dwarfed only by its vaccination rate, well over 90 percent. And in contrast to anti-immigrant sentiment elsewhere, it aspires to be a “welcoming community.”

How to explain such strong support for activist government? Not just in Concord but in much of Massachusetts and New England, a civic culture, inspired by an ethic of interdependence, endures to inspire service to the common good. Concord retains government by town meeting, though it seldom draws more than a minority of citizens to the lengthy annual sessions. And it still depends on volunteers to do the arduous work of its various committees. A great many people move in and out of town without ever engaging in this civic life. Then again that was true in the past. Enough still do, with a sense of responsibility as custodians of the local heritage, that Emerson and Thoreau would take heart.

But does this civic culture have a future? With housing prices so high, the town attracts few young families, and its own sons and daughters have to move away. It will surely have to struggle in the coming years to keep faith with its past.

Robert A. Gross is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Professor of Early American History Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. He is the author of The Minutemen and Their World (1976), which won the Bancroft Prize, and of Books and Libraries in Thoreau’s Concord (1988); with Mary Kelley, he is the coeditor of An Extensive Republic: Print, Culture, and Society in the New Nation, 1790–1840 (2010). A former assistant editor of Newsweek, he has written for such periodicals as Esquire, Harper’s, The Boston Globe, and The New York Times, and his essays have appeared in The American Scholar, The New England Quarterly, Raritan, and The Yale Review.