In 1861, just two years after Alexis de Tocqueville died in Cannes at the age of 53, his friend Gustave de Beaumont issued a two-volume edition of the great political theorist’s letters and essays. Reviewing the collection in the pages of The Atlantic, the Boston art historian and critic (and translator of Dante) Charles Eliot Norton wrote of Tocqueville that “whenever men are striving in thought or in action to support the cause of freedom and of law; to strengthen institutions founded on principles of equal justice, to secure established liberties by defending the government in which they are embodied, his teachings will be prized, and his memory honored.”

These last two years have been a case in point. Interest in Tocqueville’s writings has surged in the wake of tumultuous events that have exposed for many the persistent contradictions and underappreciated fragility of the French aristocrat’s greatest subject: democracy in America. Tocqueville’s masterpiece remains one of the most perceptive and influential works ever written about American politics and society. Its insights about the importance to the American political system of widespread property ownership and religious affiliation, an independent press and judiciary, and vibrant voluntary associations have stood the test of time, its deeper reflections on the crucial relationship between liberty and equality shown to have been astonishingly prescient.

In 2004, Library of America teamed with Tocqueville scholar Olivier Zunz to publish an authoritative edition of Democracy in America in an award-winning new translation by the acclaimed translator Arthur Goldhammer (whose other credits include the bestselling English-language rendering of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.) Now Zunz, the James Madison Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Virginia, has returned with The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville, just published by Princeton University Press, the first full-scale biography in nearly two decades and the first to place Tocqueville’s commitment to achieving a new kind of democracy at the center of his life and work. Professor Zunz has kindly agreed to field a few questions.

Library of America: Thank you, Olivier, for taking time out to speak with us, and congratulations on the new book. In addition to the Library of America edition of Democracy in America you have edited numerous books by and about Tocqueville and you have spoken elsewhere about your “long friendship” with him. What is it about Tocqueville that keeps you coming back?

Olivier Zunz: Tocqueville had a genuine gift for lasting friendship, and he was an indefatigable letter writer. Here is a man who was shy and diffident, never at ease with colleagues in the Chamber [the French legislative assembly, in which Tocqueville served for more than a decade], and yet he forged deep friendships, sustained through richly detailed correspondence. The galaxy of correspondents included American informants (abolitionist and senator Charles Sumner, historian Jared Sparks, political philosopher Francis Lieber), British friends (John Stuart Mill, economist Nassau William Senior), and some of the most important men and women of his time in France. He corresponded not only with intellectual and political figures but also with family members, old friends of his teenage years, and of course constituents. Correspondence was a daily activity. Of the thirty-two volumes of his complete works, eighteen are exclusively volumes of correspondence, revealing to the reader his engrossing debates with colleagues in the Chamber and the Academies, conversations in the Parisian salons of the July Monarchy, details about his electoral campaigns, among many other things.

As a biographer, reading this immense collection of letters closely, I came to share Tocqueville’s emotions, to worry about his responses to events, and to identify with the issues he faced. The main thing these letters did for me was to convince me of Tocqueville’s integrity in both expressing his convictions and voicing his doubts, and this gave a moral quality to the life I tried to narrate. This is how we became “friends.”

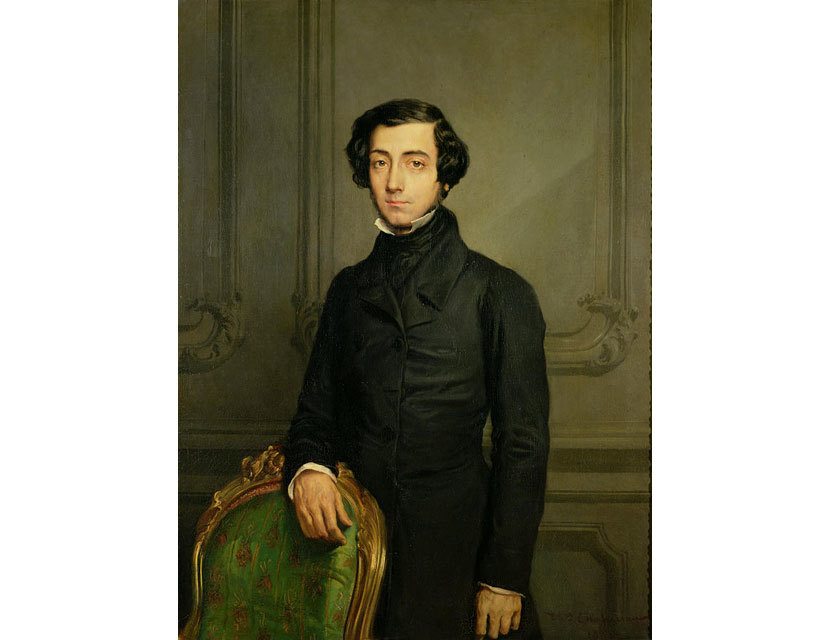

LOA: Later in his life, while researching the book that would become The Ancien Régime and the Revolution, Tocqueville offered this assessment of Edmund Burke’s 1790 Reflections on the Revolution in France: “The character of general fact, the universality, the sense of finality and irreversibility in the Revolution escape him entirely. He remains buried in an ancient world—its English stratum—and cannot grasp the new and universal thing taking shape.” How was Tocqueville, a scion of an aristocratic family who would seem to have had every reason and motive to remain likewise buried, able to see and understand democracy, “the new and universal thing,” for what it was?

Zunz: I must point out the significance of the American experience. It is important to realize that before the American trip, Tocqueville, like all his family members, friends, and wider connections, had a strictly negative view of equality, a word they used interchangeably with democracy. Equality meant levelling, the end of privileges for their caste, and in the same movement the end of aristocratic liberty that benefited them. In aristocratic lexicon, equality was a bad word.

What Tocqueville found in America, to his surprise, was a society where equality of status at birth—for the white population, that is: Tocqueville, a committed abolitionist, was always clear about that—could generate the liberty for ordinary citizens to realize their potential, to achieve their lives.

You quoted Charles Eliot Norton to begin this conversation. Norton seized on Tocqueville’s essential proposition and rephrased it as a simple question for Americans to ponder: “Can equality, which, by dividing men and reducing the mass to a common level, smooths the way for the establishment of a despotism, either of an individual or of the mob, be made to promote and secure liberty?” Tocqueville understood that question better than anybody else and answered it positively. We are still asking the same question as we struggle to enlarge the circle of the “we.”

This being said, Tocqueville was fearful of democracy’s excess, and he had some amazing convergences with Burke without acknowledging them. Burke turned out to be a kindred spirit with whom Tocqueville shared several profound insights. A point that caught Tocqueville’s special attention was Burke’s assertion that the French were “not fit for liberty,” just as Tocqueville had said repeatedly in heralding America as the example to follow. Burke argued that the French were lacking what he called “a certain fund of natural moderation to qualify them for freedom” and instead misused their newfound liberty to illiberal ends. Tocqueville could not agree more.

LOA: Let’s turn back to Tocqueville and Beaumont’s 1831 trip to the United States, a nine-month journey that forever changed the course of Tocqueville’s life. Though it would eventually encompass the four corners of the young republic (and a side trip to British Canada) and interviews with more than 200 individuals about a wide range of topics, the official rationale for the trip was to study American penitentiary systems. Why is this significant? What did a close examination of prisons reveal about American attitudes toward liberty and equality?

Zunz: In Democracy in America, Tocqueville would explain, “I know of only two ways to achieve the reign of equality—rights must be given either to each citizen or to none.” The prison report, which preceded Democracy in America by two years, focused on the second way. Through his work on American penitentiary systems, Tocqueville applied the conceptual framework that the French historian François Guizot had first suggested of viewing institutions through the lens of equality. In this case, the focus was on the equality that is produced when you take freedom away. The report highlighted that all convicted criminals in the American penitentiary were treated equally regardless of what their rank had been in free society. In prison, they were all reduced to the lowest common denominator. The language could not be clearer: “There is even more equality in the prison than in society. All have the same dress and eat the same bread. All work.” The American penitentiary, then, was an inverted America. For free Americans, equality meant access to opportunity; for imprisoned criminals, equality kept them all at the same low level. Life in American penitentiaries, the report eventually showed, had much to say about democracy. It was a microcosm of an extreme social state of equality for all, with liberty for none, a cautionary tale of what could be called a failed democracy.

LOA: In a book that is full of them, Tocqueville’s insight in Democracy in America about the importance of voluntary associations, his recognition of, as you describe it, “the power of human connections,” stands out as especially significant. What, from Tocqueville’s perspective, made civic organizations so crucial? Did Tocqueville see a causal link between the relative weakness of these institutions in France and its tendency to swing violently from revolution to reaction?

Zunz: Tocqueville’s concept of associations as the foundation of civil society is his best known and most lasting contribution to democratic theory and a significant addition to American political science. In the Federalist, Madison and Hamilton had recognized not associations but factions as a reality of American politics, and they feared them as “adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” The only way Madison saw to counter factions’ negative effects was to multiply them so that they would cancel each other out. In his farewell address (1796), Washington blamed factions for obstructing the work of government. John Quincy Adams still echoed that feeling in his conversations with Tocqueville in 1831.

Tocqueville rejected this analysis. He conceived of associations in a new and positive light. In praising a nation of joiners, Tocqueville became, unexpectedly, wildly influential. With a series of brief chapters on political parties, the press, and political associations, Tocqueville made a large and original contribution to American political theory. In analyzing the Constitution, he had followed his American sources and informants closely. Regarding associations, however, Tocqueville taught Americans how to understand themselves anew, quite a daring thing to do for a young man who had not even spent a full year in the country.

But this was the strangest of theoretical constructions, and it says a lot about how Tocqueville could reason from abstractions. Tocqueville explained that Americans knew how to employ voluntary associations to initiate change:

Suppose a person conceives of an idea for a project that has a direct bearing on the welfare of society. It would never occur to him to call upon the authorities for assistance. Instead, he will publicize his plan, offer to carry it out, enlist other individuals to pool their forces with his own, and struggle with all his might to overcome every obstacle. No doubt his efforts will often prove less successful than if the state had acted in his stead. Overall, however, the result of all these individual enterprises will far outstrip anything the government could do.

He described the process so concretely that one would believe he had observed it in detail in America, though in fact he had not. Tocqueville attended an anti-tariff convention in Philadelphia to promote free trade. A free-trade convention is not an association, but Tocqueville could reflect on how like-minded people communicated, met, and bonded to achieve a common goal, and this was a revelation to him. He also took notes on the temperance movement, also in Philadelphia.

But this is the extent of his notes on associations, not much compared to what he missed! Tocqueville traveled along the Mohawk valley in upstate New York, along the Erie Canal, in 1831, and amazingly never heard of the Second Great Awakening and its emerging benevolent empire of Bible, tract, and missionary societies, Sunday schools, educational associations, and local charities. He left no record of discussing them with any of his upper-class informants. And yet, despite this huge gap in his documentation, Tocqueville imagined the associative impulse in his own mind and rendered it with amazing clarity.

Remarkably, it was in reacting to the French political situation that Tocqueville developed a theory of association that turned out to be so significant in American political theory. The idea came to Tocqueville as he was fighting political repression at home, where all associations were experiencing a renewed level of political scrutiny from a repressive government. The problem was old, and Tocqueville had been aware of it since childhood. Much of his father’s job as a royal prefect during the Restoration had been to keep presumably politically dangerous associations under control. As Tocqueville was writing Democracy in America, the July Monarchy limited the right to associate after a workers’ insurrection in Lyon in April 1834. All associations of more than twenty members had to be granted prior authorization (the previous threshold had been thirty). “What can public opinion accomplish when there are not twenty people united by a common bond?” Tocqueville wrote pointedly in Democracy in America to be sure the French reader recognized his target.

LOA: How would you describe Tocqueville as a stylist? Many have noted a pronounced ambiguity in the arguments in Democracy in America, so effectively does he challenge his own propositions in the text. As Tocqueville himself recognized, this resulted in his writing appealing “to many people whose ideals are contrary to my own, not because they understand me but because they lift out of context arguments that align themselves with their fleeting passions.” Does this feature of his technique in some measure account for Tocqueville’s continuing appeal across the American political spectrum today?

Zunz: Now and then, Tocqueville shared his drafts with a select group: his father, his brother Edouard, his friends Kergorlay and Beaumont, all of whom pushed Tocqueville to perfect a style that would reach the widest possible audience. For childhood friend Kergorlay especially, style was as important as substance. Kergorlay knew little about America, but he had definite ideas about style. He felt “people are very superficial, and their judgment of what is deep and substantive is in reality a surface-level appreciation of style.” Kergorlay advised Tocqueville early on to emulate a trio of great masters: “Read a few sentences of Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Pascal; these ought to be your mentors.” Tocqueville took the advice to heart and practiced it daily.

Tocqueville meant to express his ideas “in as few words as possible . . . in the simplest and most intuitive order.” Beaumont testified that “form was his master,” so much so that he occasionally rewrote the same sentence twenty times. Tocqueville read his drafts out loud to family and friends. He once told Beaumont, “I’ll end up asking you to comment on how to sign my name.” One can see in Tocqueville’s manuscripts his many rewrites to achieve perfect form.

For Democracy in America, Tocqueville chose a classical style—the means of expression best adapted to a rigorous inquiry and the presentation of a “new political science for a world completely new.” He so thoroughly adhered to this standard that Hervé de Tocqueville at times reminded his son not to be too theoretical and to animate his descriptions for the benefit of the reader.

Family and friends were concerned about a potentially hostile readership that was not yet ready for democracy and required convincing. Tocqueville’s father and his brother Edouard insisted that he should communicate clearly that he was not proposing simply to import American solutions to France, lest readers dismiss the book outright. Hervé de Tocqueville and Kergorlay especially wanted to make sure that their fellow Legitimists pay attention to what Tocqueville had to say. At the same time, Hervé advised his son to tone down conclusions that might be seen as critical of the Orléans regime, and not to attack King Louis Philippe in ways that could be damaging to his career. Edouard several times intervened firmly to prevent his brother from too obviously addressing current political fights rather than the larger issues of democracy.

All this fueled Tocqueville’s innate penchant for complexity. As Tocqueville explained to his friend Chabrol, “The deeper one goes into any subject, the vaster it becomes, and behind every fact and observation lurks a doubt.” His doubts and the advice of others led Tocqueville to make a number of concessions to opponents of democracy. French critic Sainte-Beuve pointed to Tocqueville’s overuse of such qualifiers as “mais,” “si,” and “car” (but, if, because) that distracted the reader from the main message. That Sainte-Beuve and Tocqueville never warmed up to one another may partly account for the criticism, but Sainte-Beuve was correct that Tocqueville rarely made a point without giving ample space to the opposing view. Tocqueville highlighted opposing viewpoints as a rhetorical strategy designed to bring readers around to the one the author advocated. Tocqueville always expressed his conviction. But as he gave contradictory opinions almost equal time, readers often found ammunition for positions contrary to the one Tocqueville favored. An unexpected outcome is that Tocqueville has inspired readers of opposite political persuasions who have always felt free to choose their preferred formulation to claim him. Only readers who have engaged the text fully have come to recognize the author’s deep convictions, as he revealed them in small installments, by virtue of subtle repetitions, throughout the volume. All along, Tocqueville strove to reach stylistic purity while presenting controversial ideas. The peculiar result was a book at once pleasurable to read and hard to grasp fully.

LOA: “The best translation is never anything but a cheap copy!” So Tocqueville wrote to one of his many American correspondents, urging him to read the just published The Ancien Régime and the Revolution in French. We may be biased, but we think that Tocqueville might have felt differently about translation had he lived to read Arthur Goldhammer’s translation of Democracy in America, which was awarded the prestigious Translation Prize by the French-American Foundation in 2004. As a native French speaker yourself, how would you characterize Art’s approach?

Zunz: Translating Tocqueville has always been a challenge as evidenced by Tocqueville’s correspondence with Henry Reeve, his British translator. Translation is the enemy of ambiguity. In one letter, Tocqueville reproached Reeve for making him too much a foe of monarchy; in another, too much one of democracy. Tocqueville’s comment about translation being a cheap copy was addressed to Francis Lieber with, as you point out, the injunction to read L’ancien régime et la révolution in French. Years earlier Lieber had done a questionable job in translating the prison report. Art Goldhammer’s translation of Democracy in America for LOA is an act of magic. Art managed to prove Tocqueville wrong by combining fluidity and complexity just as Tocqueville intended. It was my exceptionally good fortune to work with Art on the LOA edition.

Olivier Zunz is the James Madison Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Virginia and the author of The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville and Philanthropy in America: A History, among other works, and the editor of Tocqueville’s Recollections, Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont in America, and The Tocqueville Reader: A Life in Letters and Politics.