John James Audubon (1785–1851)

From John James Audubon: Writings & Drawings

John James Audubon was born in Haiti 237 years ago, on April 26, 1785.

Initially named Jean Rabin, he was the illegitimate son of French merchant Jean Audubon and a chambermaid, Jeanne Rabin, who died seven months later. In 1794, when his father and stepmother filed adoption papers after they had moved back to France, his name was recorded as Fougère Audubon. In 1800, he was baptized as Jean-Jacques Fougère Audubon. Three years later, the elder Audubon arranged to send his son to the United States to avoid conscription during the Napoleonic Wars. After the 18-year-old arrived in America, he anglicized his name as John James.

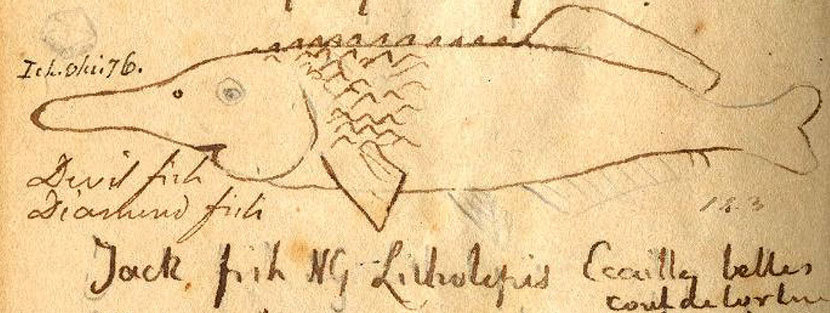

While living with his wife and two sons in Kentucky during the 1810s, John James Audubon met his match when a fellow French immigrant, the vivacious and arrogant naturalist Constantine Rafinesque, showed up at his door. Among Rafinesque’s many accomplishments are his identification and naming of nearly seven thousand plant species and hundreds of animals. In an essay on Rafinesque, John Jeremiah Sullivan writes, with slight exaggeration, “Audubon is the only person on record as ever having actually liked Rafinesque.” It’s probably more accurate to say that anyone who was initially impressed by Rafinesque—and there were a few early defenders—soon soured on him. Audubon’s advantage was that he had to put up with Rafinesque for only a week, and even that was a strain on his and his family’s forbearance.

Whatever the true nature of their friendship, it later became apparent—long after both men were dead—that during this visit Audubon pranked Rafinesque by inventing at least twenty-six species of animals and (for good measure) two plants, which Rafinesque unquestioningly included in his books and articles. Knowing this fact will entirely change for readers the meaning of the often-hilarious account Audubon wrote about the week Rafinesque stayed in his home. We present Audubon’s essay, “The Eccentric Naturalist,” as our Story of the Week selection, with an introduction offering additional details about his now-infamous hoax.