World War II Memoirs: The Pacific Theater, Library of America’s first release of 2022, brings together the firsthand perspectives of three Americans who came of age fighting in the Pacific and who survived to tell their stories. Remarkable literary achievements that capture history with the immediacy of lived experience, all three—With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, by E. B. Sledge; Flights of Passage: Reflections of a World War II Aviator, by Samuel Hynes; and Crossing the Line: A Bluejacket’s Odyssey in World War II, by Alvin Kernan—are classics of the modern literature of war.

The book’s editor is Elizabeth D. Samet, professor of English at the United States Military Academy at West Point and the author of Willing Obedience: Citizens, Soldiers, and the Progress of Consent in America, 1776–1898; Soldier’s Heart: Reading Literature Through Peace and War at West Point; and No Man’s Land: Preparing for War and Peace in Post-9/11 America. Samet’s most recent title, published in the fall of 2021, is Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness.

Via email, Samet discussed the three books and their authors with Library of America. (The views expressed in this interview do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.)

Library of America: Hundreds of memoirs have been written by Americans who served in the Pacific in World War II. What makes the three works collected in this volume stand out among them?

Elizabeth D. Samet: Memory is an inconstant ally, perhaps especially so when episodes of violence and death form the core of remembrance. Memories of war are filtered through a welter of emotions and passions: grief, horror, wonder, pity, pride, rage, love, shame, regret, nostalgia. Then, too, there is the complicated business of reconstituting private memory for a public audience. Effective memoirists draw on the fiction writer’s arsenal. They retell events out of sequence to heighten dramatic effect, they dwell on certain events and omit others to create a clear thematic arc, they navigate the inevitable distance between the protagonist of their tale and the teller they have become. I’m reminded of the beginning of Charles Dickens’s autobiographical novel David Copperfield: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life,” David proposes, “or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.”

Of course, if there is no shaping or polishing, the memoir will prove unintelligible to anyone else. If there is too much manipulation, however, a reader will become suspicious: no life story has the definitive symmetries, epiphanies, and reversals of a plot. The works of Kernan, Sledge, and Hynes navigate this terrain with great skill. These writers are willing to present themselves thinking rather than insisting that they have already figured everything out. The fact that all three went on to academic careers is significant because they were as deeply invested in the life of the mind as they once had been immersed in the sphere of violent action. They believed in the force of language as a weapon against the seemingly incomprehensible.

LOA: What can readers learn about the war in the Pacific from these works? How do they challenge common preconceptions and myths about the war?

Samet: We tend to neglect the Pacific Theater in favor of the European. The latter offers a story that is less murky and more flattering: the portrait of the American G.I. as a righteous liberator. The war in the Pacific, meant to avenge the attack on Pearl Harbor, was infused on both sides with racial animosity and a corresponding brutality. The war against Japan is also intertwined with a domestic reality we would prefer to forget: the internment of Japanese Americans.

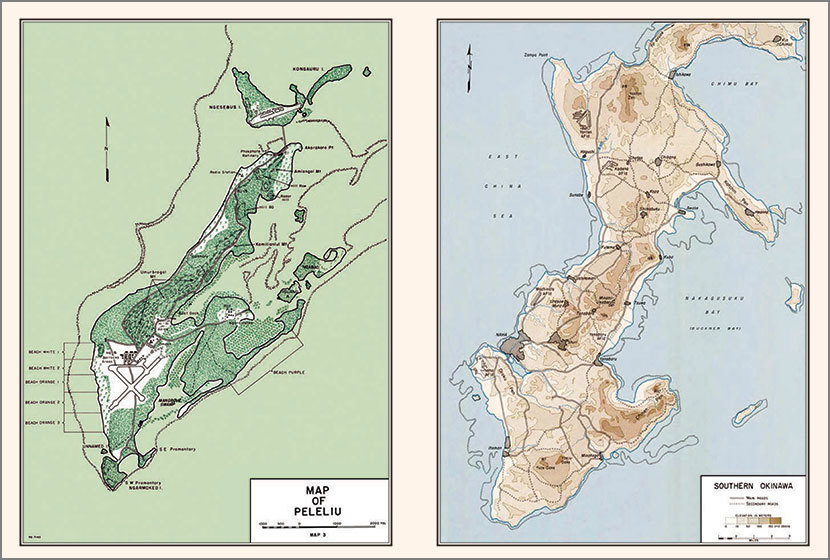

Reading about the Pacific Theater demands a reckoning with all of these elements. It also involves us in a different geography and kind of fighting: it focuses on naval warfare as well as on aviation and ground combat. These three memoirs provide us views from land, air, and sea: Sledge writes from the perspective of a Marine infantryman in the midst of battle for extended periods. Hynes introduces us to the incongruities of the life of a pilot hopping from island to island, risking his life in the air while spending his nights drinking with his comrades. Kernan, who enlisted in the Navy before the war began, gives us insight into American military culture on the eve of the war as well as into the isolation of life on an aircraft carrier and the danger of flying missions as an aerial gunner.

LOA: Samuel Hynes writes of the generation who came of age during World War II, “We grew up on active duty. I entered Navy Flight School when I was eighteen, and I was not twenty-one until two weeks after the war ended, and most of the young men I flew with were roughly my age.” Eugene Sledge and Alvin Kernan were also in their late teens when the war began. What can these three coming-of-age stories tell us about America in the 1940s, and about how the war changed American society?

Samet: In Flights of Passage, and to an even greater degree in Crossing the Line, we gain insight into the ways in which the Depression shaped the generation that fought the war. While Hynes and Kernan do not spend a great deal of time talking about their prewar lives, it is clear that family turbulence and economic hardship informed their attitudes, while the G.I. Bill enabled them eventually to pursue the education that would make possible their academic careers.

With the Old Breed adds the dimension of regionalism to our understanding of the period: Sledge, who was from Alabama, identifies as a southerner and has a particular perspective on military service rooted in his ancestors’ participation in the American Civil War. Several episodes in his book reveal the ways in which these two mythic conflicts intersect in the national imagination.

LOA: Eugene Sledge became a professor of biology after the war. In a letter to a reader, he explained that With the Old Breed was written in a style he had learned “composing articles for scientific journals,” one that valued “precision in writing.” Do you think his narrative reflects his scientific background? How does it compare with the memoirs of Hynes and Alvin Kernan, who both became distinguished literary scholars after the war?

Samet: Sledge is talking about the writer’s discipline, which all three memoirists shared. Perhaps he is more attuned than are Hynes and Kernan to nature—and to the ways in which war disfigures the natural world as surely as it does the man-made one. In comparison to Sledge’s prose, Hynes’s writing may be more lyrical, and Kernan’s more economical, frank, and uncompromising, but these three authors are alike in the precision of their observations, their refusal to reduce complexity or to resolve ambiguity, and their insistence on remembering the proximate as well as the lingering costs of war.

LOA: Besides the three works collected in this volume, are there other memoirs by Americans who fought in the Pacific that you would recommend to readers?

Samet: Robert Leckie’s Helmet for My Pillow recounts the author’s experience with the 1st Marine Division in the Guadalcanal Campaign. Sy M. Kahn’s war diary, subsequently published as Between Tedium and Terror, provides a window onto an often overlooked part of war in its account of life in a port battalion of the Army Transportation Corps in the Southwest Pacific. Saipan: The War Diary of John Ciardi, discovered only after Ciardi’s death in 1986, is an elegant, searing chronicle of the distinguished poet and translator’s experience as a gunner on a B-29. Readers curious about the exploits of one of the more celebrated units of the war, Merrill’s Marauders, which operated in the jungles of Burma, will want to read Charlton Ogburn’s The Marauders.