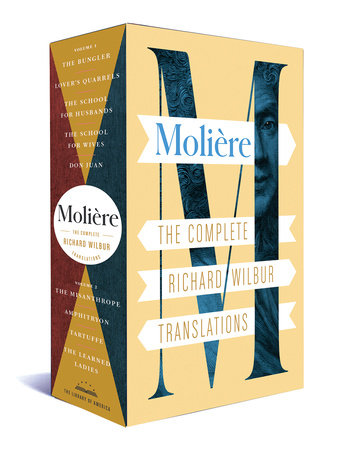

French playwright Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, better known by his stage name Molière, was baptised 400 years ago on January 15, 1622. To commemorate the quadricentennial of this giant of world literature, and to celebrate the art of literary translation, Library of America has just released Molière: The Complete Richard Wilbur Translations, a two-volume boxed set containing all ten of the verse recreations that American poet Richard Wilbur made of Molière’s plays over a period of more than fifty years.

The Library of America Molière/Wilbur edition includes a foreword by Adam Gopnik, staff writer at The New Yorker and an Officer of the Légion d’Honneur. Gopnik recently delved deeper into Molière’s art, and the brilliance of Wilbur’s renderings of the dramatist, in a series of three online lectures he made for the 92nd Street Y in New York City. Below, we offer a transcribed excerpt from his introductory talk, followed by the complete video at the bottom of the page along with links to the second and third lectures.

(Note: Among the Molière plays discussed by Gopnik in the following remarks are three—The Miser, The Imaginary Invalid, and The Bourgeois Gentleman—that Richard Wilbur never translated and that consequently don’t appear in the Library of America set.)

Molière then begins to write a series of comedies over an eleven-year span in the 1650s and ‘60s that are really the heart and the core of his achievement as we recognize it and understand it today. What’s fascinating about these comedies is that though they often glance up at the court and they often include the kind of elaborate toadying compliments that were essential to any author’s success right up until the time of the Romantics, and include elaborate compliments to the king and court, their setting is not particularly ennobled and not particularly aristocratic. Their setting instead is again among the middle classes (for the most part), whom Molière understood very well.

What’s fascinating about them is that Molière arrives at, I wouldn’t call it a formula, but at an idea about comedy which is still, I would think, the single strongest idea of comedy as we enjoy it on television, in TV series, on stage; whether it’s Neil Simon or Jerry Seinfeld, or Larry David, it’s the way we think about comedy now. That is, people living in essentially prosperous or peaceful domestic circumstances, middle-class bourgeois families, who suddenly are afflicted by somebody who has an obsession. Now that’s the way—if anybody here watches Curb Your Enthusiasm, Larry David’s wonderful show—that’s what happens every week on Curb Your Enthusiasm, right? Larry David is living this extremely prosperous life, everything seems to be peaceful, and then he gets obsessed with something that violates social decorum. His feelings are wounded because he’s treated in a cavalier way in a latte shop, or he recognizes that he doesn’t have the best seats at the Yom Kippur memorial. Whatever it is, he gets obsessed with it and the social decorum gets violated and the comedy arises from the violation of that social decorum and everyone’s frantic efforts to heal, to re-sew and mend the tear in the social decorum.

Molière invented that kind of comedy and that’s what happens again in all of the great comedies that Molière writes over that eleven-year period. The Miser involves a sudden obsession, as the title suggests, with money. Tartuffe, one of the greatest of all comedies, is about the folly of piety—a middle-class family invite a supposedly pious man into their inner circle, a kind of saint, a priest, who turns out to be an avaricious lecher. The Learned Ladies, which is very much about a sudden mania for education—people, women in this case, who are leading more or less normal lives suddenly have a mania to get more learning. It sounds as though it might be an anti-feminist play but in fact it’s just the reverse (I want to talk about that in a little while). The Imaginary Invalid I’m sure you’ve heard of: again, the violation, the Pandora’s box gets opened—an obsession is introduced, an obsession with health when we all know all too well somebody who’s convinced at every moment that he’s got every ailment going and is about to is about to die of it. The Bourgeois Gentleman—again, some of you may remember that from performances or from college. . . . This is about a wealthy bourgeois who’s trying to become a nobleman and he thinks he’ll do it by getting himself educated. So he calls in a poetry master, a rhetoric master, who explains to him that there’s poetry and prose, and the bourgeois gentleman (or would-be gentleman) suddenly realizes he’s been speaking prose his entire life and he can’t get over it, nobody had ever told him that he was capable of speaking prose.

Finally, maybe the greatest of all Molière’s comedies (and we’ll talk about it at greater length in a moment): The Misanthrope. Now The Misanthrope—actually, I mentioned Larry David a moment ago—is pure Larry David. It’s set in a slightly higher social setting than a play like Tartuffe or The Bourgeois Gentleman: the people in The Misanthrope are of a slightly more elevated literary and aristocratic culture than the others but still [belong to] very much a recognizable Parisian social world. The hero, Alceste, decides that he is fed up with the social lies we tell each other at every moment in our lives—the way when somebody shares with us their new poem or their new story we all say, Oh, it was wonderful, or, you know, the most famous thing is when you go backstage when a friend has been in a play or put on a play and you’re obligated to say, Oh my god it was wonderful. Stephen Sondheim, to name one, used to be very funny about this—you know that the best thing to say when you were in that situation was, “Only you could have done this, only you could have done this,” which can mean absolutely anything from “It’s so sublime only you could have done it” to “A mess like this is one only you could be responsible for.”

Anyway, we tell those kinds of small social lies every minute in order to maintain social peace and Alceste, the hero, is understandably, not incorrectly, totally disgusted with the sheer magnitude and dailiness of the lies we tell and insists that he will be the one truth-teller. So in each of these plays, suddenly, into the normal rhythm of human hypocrisy is thrown a new fanatic belief—and from that clash between fanaticism and normality, between an extreme case and the daily case of our lives, Molière makes comedy.

Watch the complete talk: Adam Gopnik on Molière, Session One

Adam Gopnik on Molière, Session Two

Adam Gopnik on Molière, Session Three