By Geoffrey O’Brien

The second adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel returns to the book’s wildest extremes, bringing to the fore elements the earlier version could only hint at.

Guillermo del Toro has made something of a specialty of materializing ghosts—whether in the war-racked orphanage of The Devil’s Backbone (2001) or the dilapidated, moth-infested mansion of Crimson Peak (2015)—so it is perhaps not totally surprising he has chosen to resurrect William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel Nightmare Alley, which culminates in just such an undertaking. Del Toro has tended to apply his visual invention toward conjuring plausible apparitions. In Nightmare Alley, by contrast, the spectral materialization in question is thoroughly fraudulent, and precipitates catastrophe for the man who has contrived it. Gresham’s book provides a virtual catalogue of the ways such phenomena can be faked—from palmistry and mindreading to well-funded pseudo-religious cults and the outer reaches of what its insiders call the spook racket.

The novel is nothing so simple as an exposé. In an extraordinary act of distillation Gresham wove the strands of his very real personal misery into a singular Song of Experience shot through with bitter self-knowledge. His mode was not memoir but myth, a myth of temptation and self-destruction decked in the grimiest of documentary details. Del Toro emphasizes that his source is the novel rather than the still enthralling 1947 film starring Tyrone Power, although he and his co-scenarist Kim Morgan have adopted a number of narrative devices and shortcuts from Jules Furthman’s screenplay. The new film returns to the book’s wildest extremes, bringing to the fore elements the earlier version could only hint at.

Gresham found his indelible central image in the world of the traveling carnival, a realm of no fixed location, the nexus of forbidden desires and the final refuge for those too broken by the world to function elsewhere. Into this degraded Eden—where the geek bites the head off live chickens to earn his next bottle—comes Stanton Carlisle, the most hapless and tormented of serpents, incarnated in del Toro’s film by Bradley Cooper. A man of cunning driven by deep inward terror, Stan will abuse and manipulate and kill if necessary to get the knowledge that enables him to make it big in the world. Rising from nightclub mentalist to spiritualist medium, conning ever richer and more powerful clients, he will tumble to his doom with the help of an icy female psychoanalyst (an archetypal personage indelibly named Dr. Lilith Ritter) who turns out to be a far more astute manipulator than he is. His doom condemns him to the lowest level of the carnival world he had sought to escape in the first place.

For those who travel with it, the carnival can represent a camaraderie affirmed by shared argot and shared professional secrets. The secrets have to do with every variety of enticing and conning and come with an implied philosophy spelled out in a handwritten manual of mentalist codes and tricks that gives Stan his roadmap to success: “Find out what they are afraid of and sell it back to them.” Gresham paints this milieu with a vividness, and an undeniable affection, that gives his characters—Zeena the fortuneteller and her alcoholic husband Pete, the waif Molly, the protective strongman Bruno—an insistent life of their own. Del Toro, a longtime student of carnival culture, plunges enthusiastically into the surfaces of that world. His camera sweeps in and out of the tents and platforms, revels in tilted angles and wide-angle distortions, takes in the lurid succession of placards and tableaus, gives glimpses of the contortionist and the spider woman and the geek in his pit and the array of malformed embryos in jars.

He achieves the effect of a bright and garish scroll unrolled without pause. We are with the insiders, sharing their tricks, but we are also the marks, duly awed by the nonstop come-on. Del Toro is a unrestrainedly visual filmmaker who sometimes seems to aspire to creating a live-action graphic novel in which figures and their surroundings are part of an unbroken pattern. Even when working with a script as tenuously conceived as the gothic Crimson Peak, he offers up intricately elaborated, continually evolving optical suites. It is fascinating to see him engage with the so much more solidly grounded materials of Nightmare Alley. He is supremely in his element when, after the geek has run mad, Stan pursues him into the carnival’s Hell House, winding his way among papier-mâché demons and through a gaping infernal maw. It is as if he ran through the corridors of his own mind, which are no less scary for their tawdry fakeness.

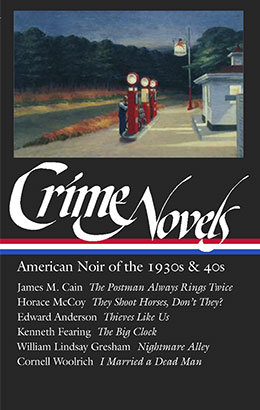

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s & 40s |

The movie, like the book, falls into two distinct parts. The breakpoint comes when Stan reveals the lowest depths of his character: he slips lethal wood alcohol to the once celebrated mentalist Pete (superbly played by David Strathairn), ditches his mistress Zeena (Toni Collette, so good in the role that one wishes she had more time on screen), and enlists the young and vulnerable Molly (Rooney Mara) as his lover and confederate. The gaudy spectacle of the carnival gives way to an increasingly demented quest for the biggest con of all, as much snow falls, impressively grandiose architecture is brought into play, and Stan meets his match in the sinister therapist Lilith Ritter. Although Cate Blanchett cuts an impressive figure as Lilith, the psychological battle for control between Stan and Lilith becomes a glacial impasse, and we even begin to wonder who after all Stan and Lilith are supposed to be, a fatal question at that juncture.

This second half of the film succeeds best when the erratic tycoon Ezra Grindle enters the picture: the mark that Stan has dreamed of, a guilt-ridden man who forced the love of his youth to abort their baby, and who is convinced that Stan has the power to summon her back. Del Toro restores an element of Gresham’s novel absent from the 1947 movie, a sense of the danger inhering in Grindle’s corporate power. His fortress-like industrial headquarters, the military deployment of his staff, and his unpredictable rages open a further political dimension in the story. Richard Jenkins brings the right note of barely controlled derangement when Grindle acknowledges to Stan (just when a costumed Molly is about to materialize as the ghost of the lost beloved) that he has committed a series of brutal unspecified crimes against women. As Molly spoils the set-up by breaking character and Grindle realizes he has been conned, the film veers to a different course, with two quick and ugly killings, followed in short order by a bloody showdown between Stan and Lilith. The violent eruptions add surprisingly little; they seem designed to perk things up for an audience that expects no less.

Del Toro has given his movie the only appropriate ending, the one laid out by Gresham—the one it would have had in the 1947 version if convention had not demanded that Stan be given at least a ray of hope. It is curious, though, that however sanitized and bowdlerized the earlier film—however much illicit sex, carnival ugliness, and loose talk about religion it had to leave out—it feels more authentically sordid than this new incarnation, which has so much more freedom to be explicit. Tyrone Power as Stan (a part he fought to play) seems at first improbably clean-cut, but his movie star glamor makes what he does and what happens to him all the more appalling; Bradley Cooper, by contrast, seems already to have reached bottom from our first glimpse of him. In 1947, even if no babies in jars were on display and the geek remained out of view, what was implied but not seen still had the power to unsettle. In 2021, by contrast, it is hard to imagine even a one-eyed embryo doing much to unsettle spectators who have already seen so much more.

Watch: Official trailer for Nightmare Alley

Nightmare Alley (2021). Directed by Guillermo del Toro. Written by Guillermo del Toro and Kim Morgan, from the novel by William Lindsay Gresham. With Bradley Cooper, Cate Blanchett, Rooney Mara, Toni Collette, Richard Jenkins, and Willem Dafoe. In theaters.

Geoffrey O’Brien, former Editor in Chief of Library of America, is the author of twenty books of poetry and nonfiction, including The Phantom Empire and Sonata for Jukebox. His most recent titles are Where Did Poetry Come From: Some Early Encounters and the poetry collection Who Goes There.