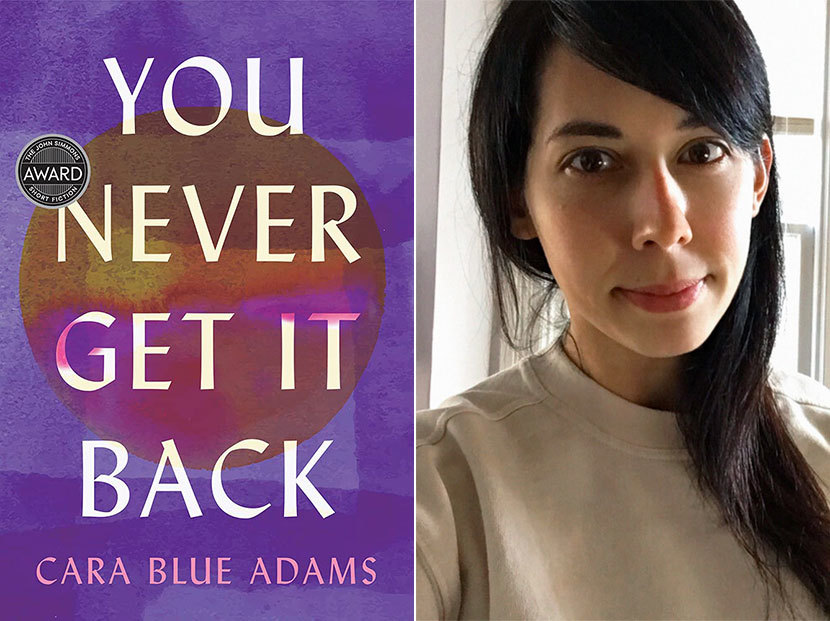

Our latest guest post by a contemporary writer comes from Cara Blue Adams, whose debut collection of short fiction, You Never Get It Back, is published this week by the University of Iowa Press.

The linked stories in You Never Get It Back follow a young woman from a bohemian and hard up New England background as she moves around the United States in her twenties and early thirties, first as a research scientist and then as a fledgling writer. Already touted as a title to watch by Jhumpa Lahiri, Interpreter of Maladies. I first read Interpreter of Maladies one March when I, much like the main character in “Sexy,” was a young woman in her early twenties living in Boston, and the elegance of the stories and their complex evocations of dislocations and losses major and minor enraptured me. Each March for several years following, I would be struck with a desire to reread the book and would do so over the course of a week or so; I only ever remembered having read it one year earlier when a receipt would fall out of the book’s pages, or when I came upon an old subway pass that I’d used to mark my place. Oh, look, March, I‘d think, and then, Oh, look, a different March. Strangely, because Lahiri is a lovely writer and it is an unlovely time of year in Boston, March became her month. Maybe March was when my life needed some loveliness. Later on, I studied the stories’ structures and the way they—the stories—speak to each other across the collection, among many other marvels, rereading them during other months, but still, when March comes, I think of her. Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping. A novel about two young sisters whose parents are gone and who end up living in rural Idaho with their formerly transient aunt, Sylvie, Housekeeping records a deep sense of abandonment. At the same time, Robinson finds the dignity and power of revelation in the ordinary. Housekeeping is narrated by the older sister, Ruth, who, with Sylvie, abruptly leaves her younger sister Lucille behind; Ruth and Sylvie are presumed dead. Later in life, Ruth imagines her younger sister, now grown, waiting without hope for her older sister and aunt to come back in a passage that works through negation and paradox: “No one watching this woman . . . could know her thoughts are thronged by our absence, or know how she does not watch, does not listen, does not wait, does not hope, and always for me and Sylvie.” This sentence, which ends the novel, is, to me, a haunting and apt evocation of an enduring loneliness, one I’ve felt myself and which prompts me to write. Elizabeth Strout, Olive Kitteridge. One of my favorite linked collections, Olive Kitteridge explores Olive’s life in Maine through Olive’s perspective and through the perspectives of her husband and various members of their community and demonstrates that an existence lived inside convention can, if we pay attention to it, become radiantly interesting. Strout isn’t afraid, either, of violence and passion and joy, all which are almost inevitably a part of what might seem from the outside like the quietest life. Strout is heir to Alice Munro, in some ways, and to Elizabeth Bishop in others—layered, complex stories that flash with insight and can seem to contain a novel; attention to landscape and a searching, precise, cool intelligence—but she is, perhaps, funnier, wryer. She understands the culture of New England, too, a culture I myself did not understand until years after I’d moved away from Vermont and Massachusetts to the Southwest. She can manage that most difficult of maneuvers, the uplifting but honest ending, and she writes with an awareness of social class; she knows that it’s a force that shapes a person. Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son. At first Johnson’s most famous book repelled me; I read it in Tucson, Arizona, at a friend’s urging and disliked it, because it felt too close to home, I see now, and because I didn’t really understand what he was doing as a writer. When I read it for the second time a few years later, it struck me as a work of genius, and it has since compelled me to return again and again. In those stories, and elsewhere, he writes with pathos and humor and a lush minimalism, along with an utterly unafraid honesty. He allows violence to erupt, as it does in real life, and for the world to fail to make sense, or for it to make a sense that is impossible. The movements of his stories are surprising, his eye for image that of a poet’s. Over time, I have come to feel that there are few fiction writers I admire more. I’ve sometimes imagined my own book as being like the book that would have been written by the daughter of the narrator, if he’d had a daughter and she’d inherited some of his intensity and restlessness and capacity for joy and sought a different kind of life. I feel a sudden desperate need here to mention Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, Robert Hayden, Robert Hass, Saul Bellow, Donald Barthelme, Lorrie Moore, James Salter, Amy Hempel, Ann Beattie, Edward P. Jones, Junot Diaz, Donald Antrim, Christine Schutt, and many other writers I’ve loved and studied and even memorized passages by—but I’ll stop myself from going on. Cara Blue Adams has published short fiction in Granta, the Kenyon Review, Epoch, Alaska Quarterly Review, and American Short Fiction. She has been awarded the Kenyon Review Short Fiction Prize, the Missouri Review Peden Prize, and the Meringoff Prize in Fiction, along with The Center for Fiction Emerging Writer Fellowship. An associate professor of creative writing at Seton Hall University, Adams lives in Brooklyn, New York.