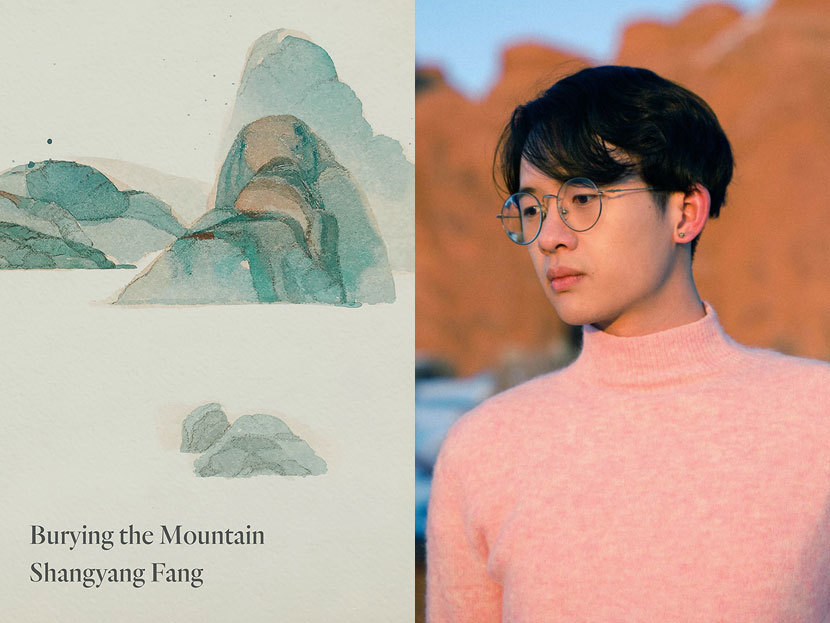

Our latest “Influences” guest post by a contemporary writer comes from poet Shangyang Fang, whose debut collection of verse, Burying the Mountain, arrives this month from Copper Canyon Press.

Fang came to our attention via a recent Georgia Review interview in which he mentions Wallace Stevens and Gertrude Stein, among other writers, as influences on his work. In the following column, he describes the ways in which a more recent group of American poets have been a source of inspiration to him.

Who’s your favorite American poet, then?

When the Customs and Border Protection officer asked me this question, I panicked. I knew that Shakespeare was not American. It was the first time I arrived at the U.S. border with the word “Poetry” on my I-20 (student visa) document. Naturally, I don’t recall my answer. But I remember the faint curve of the officer’s brows mixed confusion and dissatisfaction. It was identical to the expression I had when I first read American poetry.

I couldn’t comprehend the music in a foreign language. Until, in my sophomore year, my teacher Janice N. Harrington showed me a photocopy of the poem “Pipistrelles” by Brigit Pegeen Kelly. I was transfixed:

In the damp dusk

The bats playing spies and counterspies by the river’s

Bankrupt water station

Look like the flung hands of deaf boys, restlessly

Signing the dark. Deaf boys

Who all night and into the half-lit hours

When the trees step from their shadows

And the shadows go to grass

Whistle those high-pitched tunes that, though unheard, hurt

Our thoughts. . . .

The ghostly image of a boy’s hand superimposed with bats, knotted into one inseparable entity by the meticulous music, brought news to a young Chinese poet that a poem’s metaphoric power could create an alternate reality to replace this reality, a written existence to replace my empirical self.

After that, I carried Kelly’s collection Song with me everywhere, a slit among the bluish bricks of my structural engineering textbooks. I looked up each unfamiliar vocabulary word (and trust me, there were many) in the dictionary, translated it into Chinese, and memorized it. In Kelly’s poems, the metaphorical “is” is not only the border between things but also an engine for transformation that erases that border. In her poetry, both the speaker’s own state of being and the arranged world exist in a state of permanent uncertainty, leading me into constant belief and disbelief in the stability of this reality.

I regard Kelly’s writing as resembling Buddhist rhetoric—a sui generis way of seeing that conjures an illusion and then shatters the illusion—this is this, or that; this is not this, nor that; this is not this, and is this. Her poems seem to me a phenomenological investigation of reality demonstrating both distrust and love, weighting this world with her spiritual vision—

What flies back at us

From rocks and trees, from the emptiness

We cannot resist casting into,

Is colored by the distortions of our hearts,

And what we hear almost always blinds us.

We stumble against phantoms, throw

Ourselves from imaginary cliffs, and at dusk, like children, we

Run the long shadows down. Because the heart, friend,

Is a shadow, a domed dark

Hung with remembered doings.

I fell in love with Kelly’s language and later found, luckily, similar passions in Lucie Brock-Broido’s The Master Letters and Ishion Hutchinson’s House of Lords and Commons.

Jorie Graham is another inspiring poet who explores the notion of self in/against reality and who influenced my early writing. For a year or so in college, I brought her The Dream of the Unified Field: Selected Poems 1974–1994 with me from dorm to lab to lecture hall. After the long harsh winter in Illinois, when the magnolias started pushing their thick flesh into the wind, I read the following stanza on a stone bench under the shadow of flowers:

Late in the season the world digs in, the fat blossoms

hold still for just a moment longer.

Nothing looks satisfied,

but there is no real reason to move on much further:

this isn’t a bad place;

why not pretend

we wished for it?

I always admire Graham’s mastery in dissecting each tenuous moment of being, each sensation—when a finger is dipped into a stream of water, the moment is crystalized then multiplies, the finger multiplying with the stream into a constellation of metaphysical touching and being touched. Reading Graham, I feel an echo of Blake’s line, “Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.”

But then the question comes to this tediously discussed “self”—where is this self in the vein of history and politics, and who even is this self? I was never a fan of narrative poetry, but out of boredom I decided to give it a try. I was writing the poem “Meditation on an Authentic China” (included in Burying the Mountain) at the time—the first few drafts were ghastly. My teacher Roger Reeves, after reading it, perhaps out of sympathy, recommended I study “I Am Your Waiter Tonight and My Name Is Dmitri” by Robert Hass. The poem astonished me. Its hero Dmitri is of course a fictional character, moving through fabricated scenarios:

He never learned much English,

But he slept beside her in the night until she was an old woman

Who still knew her way to the Russian pharmacist

In a Chicago suburb where she could buy sachets of the herbs

Of the Russian summer that her coarse white nightgown

Smelled of as he fell asleep, though he smoked Turkish cigarettes

And could hardly smell.

This poem strangely reminds me of the title of “Poem Without a Hero” by Anna Akhmatova. There might be no hero at all. The individual might be fictitious, the scenario might be hypothetical, but the suffering must be real, and the happiness that comes with it is irreplaceable. Hass directs my attention, not away from the individual, but inside the individual so painfully and deeply as to elicit the collective. If each person’s heart is a walled garden, then at its earthly core there must be some roots that connect each lost, separate heart. I think that the task of poetry, then, doesn’t only involve the public exhibition of private suffering, which I respectfully disagree with anyway, but how to manifest the personal in the historical and political. Write about the garden, then write about the earth that constitutes this garden.

Shangyang Fang grew up in Chengdu, China, came to the United States at the age of seventeen, and composes poems in English and Chinese. After receiving a degree in civil engineering at University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Fang became a poetry fellow at the Michener Center for Writers at the University of Texas at Austin and is now a Wallce Stegner Fellow at Stanford University. He is the recipient of the Joy Harjo Poetry Award and Gregory O’Donoghue International Poetry Prize.