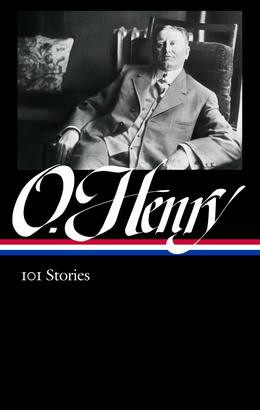

An internationally beloved writer makes his long-awaited entrance into the Library of America series with O. Henry: 101 Stories, a revelatory new collection of the master’s short fiction edited by Ben Yagoda. Organized by location and theme, with separate sections dedicated to O. Henry’s Central American tales, his Southwestern yarns, and his New York stories, 101 Stories conclusively demonstrates how much more there is to this author than such often-anthologized chestnuts as “The Ransom of Red Chief” and the sentimental holiday favorite “The Gift of the Magi.”

Critics are gratefully receiving the new LOA volume as a fresh look at a writer long overdue for reassessment. In The Washington Post, for instance, Michael Dirda praised Yagoda’s “excellent selection” and enthused, “In multiple ways, O. Henry was phenomenal. . . . Besides clever plotting that Agatha Christie would envy, his work can be touching, humorous, tragic, frightening or all of them by turns.” Writing in The Wall Street Journal, John J. Miller declared that the arrival of 101 Stories is “fresh evidence that, despite occasional skepticism from critics and scholars, O. Henry has secured a place in the country’s literary pantheon.”

Ben Yagoda is professor emeritus of journalism and English at the University of Delaware, and the author or editor of twelve books, most recently The B Side: The Death of Tin Pan Alley and the Rebirth of the Great American Song (2015). His work has been published in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Slate, The American Scholar, and Rolling Stone, among other outlets. Below, he describes the decision-making that went into 101 Stories.

Library of America: It’s safe to say most people coming to this book will know O. Henry as a writer of short stories with twist endings. What else is there to him besides that?

Ben Yagoda: It’s undeniable that O. Henry—born William Sidney Porter in 1862—liked a tale with a surprise at the end. That’s certainly true of his most famous story, “The Gift of the Magi,” as well as other well-known works like “A Retrieved Reformation” and “The Cop and the Anthem.” And you can see the beginnings of this affinity in some of his very early sketches I included in the volume, written when he was a young columnist for the Houston Post, such as “Why He Hesitated,” “Too Wise,” and “Something for Baby.”

However, statistically speaking, the majority of his stories don’t have surprise endings, and in addition aren’t sentimental, in the manner of “Magi.” But this image—and O. Henry’s relegation to middle-school textbooks—have obscured other significant qualities of his work. The most striking of these is the mood he most often turned to, the comic—though admittedly, the Mark Twain–like “The Ransom of Red Chief” has often been included in anthologies of American humor. There are dozens of other stories where he shows a great gift for satire and comic hyperbole.

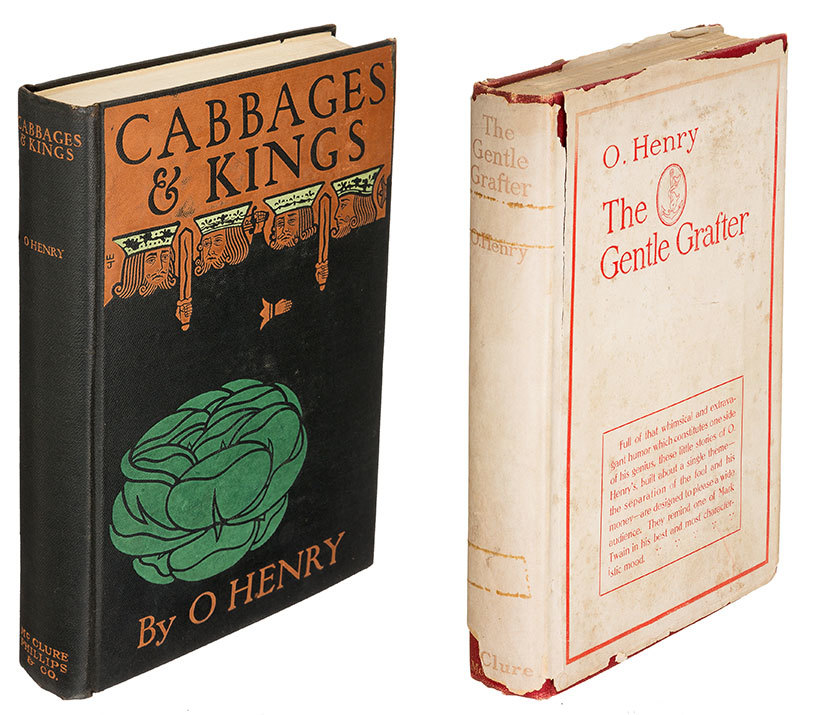

Beyond that, O. Henry painted an almost ethnographic portrait of the American con man in The Gentle Grafter, and published another sharp and clever collection of linked stories in Cabbages and Kings, about misfits and their misadventures in a fictional Central American “banana republic” (O. Henry coined the term). Born in North Carolina, he spent his twenties and early thirties in Texas, and offered a careful and affectionate depiction of the just-before-the-turn-of the-century American West in such stories as “The Return of the Troubadour.” A bit post-modernly, he wrote many self-conscious stories about writers and editors. Perhaps his most characteristic theme was hidden identity and disguise, surely influenced by his own secretiveness about the fact that he was convicted of embezzling funds from the Texas bank where he worked as a teller, spent more than three years in prison, and took great pains to hide this for the rest of his life.

Perhaps most important, he set more than one hundred stories in New York City, his adoptive hometown, during a period of remarkable change. He loved to wander the city, mostly at night, taking it all in. O. Henry’s New York stories present the city with journalistic precision and have a wide geographic, architectural, and social scope, taking place in Coney Island and the Tenderloin and Madison Square, and peopled by tycoons and shop girls, vaudevillians and bums.

LOA: Your selection of 101 stories represents well under half of O. Henry’s total output. What distinguishes the stories included in this Library of America volume from all the ones that didn’t make the cut?

Yagoda: Reading through O. Henry’s work and making selections for the book was a substantial task but not an unpleasant or arduous one. Writing so many stories, he not surprisingly produced his share of clunkers, and it was easy to eliminate dozens that were either slight or labored, that repeated a motif he had done better elsewhere, whose plot turns veered into preposterousness, or that relied too heavily on regional or ethnic dialect, a device that rarely ages well.

(I would like to say a word about O. Henry’s racism. It was as much a part of him as one would expect of someone born in North Carolina during the Civil War. In his stories, it comes out most frequently in offhand remarks by either characters or the narrator, in now-offensive terminology, or in stereotypical minor characters who speak in the aforementioned dialect.)

Of the stories that remained, my selections were designed to represent the various strains in his work described above and to give a sense of the progression of his short career, including his early pieces—at the Houston Post and a humor magazine he started and edited while living in Texas, The Rolling Stone—that showed him to best effect or prefigured his later work. In addition, several stories are of particular biographical interest. “A Call Loan” and “Friends in Rosario” are about financial irregularities in Texas banks. The central character in “Blind Man’s Holiday” has been unjustly (or perhaps not) accused of stealing from an employer.

O. Henry died of alcohol-related illness in 1910, and “The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball” is, unflinchingly, about an alcoholic. And “Let Me Feel Your Pulse” describes medical ministrations such as those received by Bill Porter in his last months.

LOA: You’ve chosen to organize the stories by setting, rather than chronologically. What’s gained by this approach, and do you have a favorite among the various locations?

Yagoda: Presenting 101 stories chronologically would be useful for observing the development of O. Henry’s skills and style but otherwise would create kind of a jumble, I think. On the other hand, when they’re arranged them by setting or theme—The Country, The West, The Tropics, “The Gentle Grafter,” New York—each section can be read as a kind of entity. You see how O. Henry explored and developed similar characters, settings, and situations.

As for my favorite, it’s got to be my birthplace, New York. It’s fascinating that O. Henry arrived in 1902, at the age of 40, having never set foot there previously, and almost immediately adopted it as his second home. Within a year he was setting most of his stories in the city, and in December 1903 was engaged by The Sunday World newspaper to write a short story every week, an arrangement that continued for a remarkable two years.

LOA: These stories demonstrate an unmistakable fondness for wayward protagonists: outlaws, rogues, ne’er-do-wells on the outside of respectable society. Is it reductive to draw a link between O. Henry’s own criminal history and his affinity for these types of characters?

Yagoda: The observation is true, but I’d extend it a little bit. He was born into a well-to-do family in North Carolina, but after he moved to Texas, he never hobnobbed with bigwigs, even after reaching a high level of literary fame in New York. His prison experience was important in many ways, including that conversations with other inmates gave him so much material—for the famous safe-cracker short story “A Retrieved Reformation,” for the con-man stories in The Gentle Grafter such as “Conscience in Art,” for a fascinating how-to piece called “Robbing a Train,” for the overlooked gem “After Twenty Years.”

In New York, he gravitated not so much to ne’er-do-wells as to those on the lower rungs of the social ladder—storekeepers, homeless people (like Soapy in “The Cop and the Anthem”), and, especially, the underpaid, harassed, and put-upon shop girls and young working women, some of whose stories he told in “The Last Leaf,” “An Unfinished Story,” and “The Trimmed Lamp.”

LOA: At least one reviewer of the new collection has suggested that O. Henry’s literary reputation suffered because of his historical position just prior to the arrival of modernism. Do you believe that explains, at least in part, why his reputation went into relative eclipse in recent decades?

Yagoda: No question. O. Henry’s reputation was at its zenith in the period just before and after his death. In 1916, an unsigned article in The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography called him “the American Maupassant” (a frequently made comparison) and “probably the greatest master of the short story that America has produced with the possible exception of Poe.” However, that same year, a New York Times article written by Joyce Kilmer titled “Is O. Henry a Pernicious Literary Influence?” quoted Katharine Fullerton Gerould, a noted fiction writer of the day, as saying, “O. Henry did not write the short story. O. Henry wrote the anecdote.” But, she went on, he “will always be read, because he is always so sentimental.”

The National Cyclopaedia view would soon give way to the Katharine Fullerton Gerould view, which would hold sway for the next century and beyond. By the late 1920s, when such diverse American writers as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sally Benson, and John O’Hara were publishing innovative short stories, O. Henry could be said to have had virtually no influence at all. The emphasis of the form turned away from plot, his strongest suit, and toward his weakest ones: nuance, subtlety, and character. The most influential international past masters would be not Guy de Maupassant but Anton Chekhov, James Joyce, and Katherine Mansfield. That is to say, for about 100 years, it has been considered passé to write a short story with a surprise ending or even, for the most part, a robust plot.

O. Henry’s only connection to modern writers of short fiction is that since 1919, the annual award for the best published short story has been called the O. Henry Prize. I would venture to say that none of the winners would consider him an influence.

LOA: Do you have your own favorites in the collection? Are there are any stories that would be a particularly good place for first-time readers of O. Henry to start?

Yagoda: Assuming people have read “The Gift of the Magi” and “The Ransom of Red Chief” (and if not, they should), here are some places to start:

“After Twenty Years”

“The Caballero’s Way” (where he introduced the character “The Cisco Kid”)

“Conscience in Art”

“The Cop and the Anthem”

“Hearts and Hands”

“The Last Leaf”

“A Retrieved Reformation”

“Tommy’s Burglar” (a meta short story about short stories)

“The Trimmed Lamp”

“An Unfinished Story”