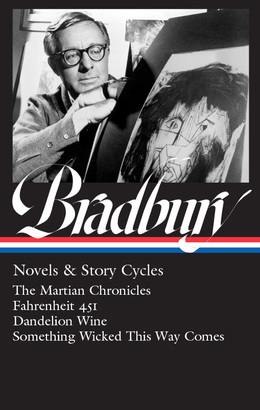

Today we’re pleased to welcome back novelist and poet Amit Majmudar, whose appreciation of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian appeared in this space last fall. In his latest guest post, Majmudar pays tribute to the singular genius of Ray Bradbury, prompted by the release last month of Ray Bradbury: Novels & Story Cycles, LOA’s inaugural Bradbury volume.

By Amit Majmudar

Mention Ray Bradbury, I’ve found, and faces light up. Strangers reach out to you on Twitter with testimonials. A voice changes on the phone, as if you just mentioned a childhood best friend. This is something beyond fondness and beyond admiration. The name conjures up poignant wonder; the name exhilarates the imagination. No one seems to be just “familiar with his work.” You’ve either never read him, or you love him.

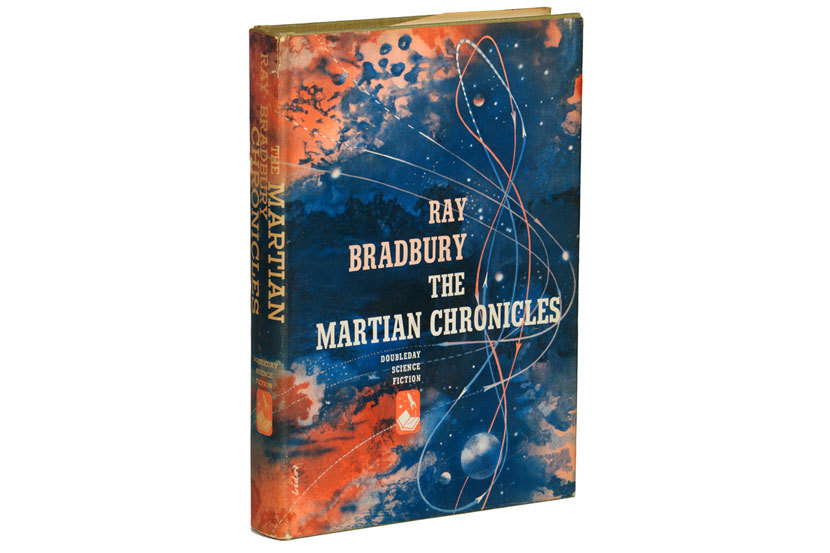

One place to read his best work (his stories are as innumerably luminous as stars) is in Library of America’s new omnibus, which contains The Martian Chronicles, Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, and Something Wicked This Way Comes.

It’s illuminating to have them all in one place. You can see, in the early work, the later work in embryo. “Usher II,” a story from The Martian Chronicles, speaks of an exterminationist campaign against fantasy literature, a theme that dovetails with Fahrenheit 451. An ethereally robed Martian, shot dead, falls “like a small circus tent pulling up its stakes and dropping soft fold on fold.” This image flows into the carnival memories of Dandelion Wine and from there into the sinister beauty of Something Wicked This Way Comes.

You can also see his most wrenching theme in all its iterations: The past. The men of the doomed third expedition to Mars encounter long-dead loved ones, who welcome them—and slaughter them. The “dark carnival” promises a return to youth—in exchange for eternal captivity. The firemen of Bradbury’s dystopia go the other way and incinerate the past wholesale. Trying to live in the past is tempting, but fatal; trying to forget the past entirely is a different kind of death. The wisest, sanest approach to the past is to turn it into dandelion wine, that treasured distillate of nostalgia, which Bradbury has bottled for us in his books.

His body of work is at home in the past and in the future at once. Visions of the far reaches of space are “grounded” in the early twentieth-century Midwest. The emblematic image comes early in this volume, when that third expedition hears “Beautiful Ohio” playing uncannily across the alien landscape of Mars. This is one secret of his charm and timelessness. Bradbury, the prophetic visionary, never stops being Ray, your next-door neighbor.

Those visions can break your heart in the ways they contrast with—and match—the present. Bradbury’s Martian stories have dates. In the 2005 of the book, Americans walk the surface of another planet. In the 2005 that Bradbury lived to see, Americans were walking the alien, ancient landscapes of Iraq and Afghanistan. In both the book and the reality, they leave an imperial desolation. Our aggressively ignorant contemporaries do not use fire to destroy physical books, as they do in Guy Montag’s world, but social media, with its faux-moral crusades against writers past and present, stinks of kerosene. I am unaware of any attempts to attack Bradbury’s legacy so far, but if they ever try to cancel him, they are going to have a war on their hands.

Bradbury has the three qualities by which T. S. Eliot defined the greatest poets: “abundance, variety, and complete competence.” It feels right to speak of Bradbury as a master poet. Whenever he unleashed his natural lyricism, he created Baroque sentences best understood, and appreciated, as a poetry far more kinetic, intense, and, well, poetic than what goes by the name of poetry, whether in academia or on Instagram.

And while the wave of applause came in, crashed, and went back down the shore, he looked again to the maze, where the sensed but unseen shadow-shapes of Will and Jim were filed among the titanic razor blades of revelation and illusion, then back to the Medusa gaze of Mr. Dark, swiftly reckoned with, and on to the stitched and jittering sightless nun of midnight, sidling back still more.

Go ahead and marvel at the metaphors, the classical allusions, the paradoxes, the synoptic syntax that sees and shows the reader everyone in the scene (Bradbury wrote screenplays, too): How rare this is! Especially in the twentieth century, in the century of Raymond-Carveresque, “well-crafted” literary fiction. (“Usher II” contains a dig at Hemingway and realism: Bradbury knew his antithesis early on.) Listen to how nothings multiply in

the Mirror Maze, the empty oblivion which beckoned with ten times a thousand million light years of reflections, counter-reflections, reversed and double-reversed, plunging deep to nothing, face-falling to nothing, stomach-dropping away to yet more sickening plummets of nothing.

The meta-miracle is how Bradbury’s supercharged writing can go unnoticed. You can race right past his beautiful complexity to find out what happens next. I know I did, when I was younger. My revisiting of Bradbury has been a reenvisioning of Bradbury. As early as high school, reading “All Summer in a Day” and Fahrenheit 451, I knew he was a great storyteller. Now I recognize him as a total word-wizard—capable, like Shakespeare, of using language in ways that combine poetic magic, emotional weight, and dramatic tension. This writer sacrifices nothing.

Which is why this volume is going straight from my desk to my thirteen-year-old son’s. He wants to be a writer, and this is the only teaching text he needs. One day, he, too, will smile reflexively at the mere mention of this writer’s name. He, too, will become a member of what may well be one of the biggest fan clubs in American letters. Best to join early and let Bradbury influence him into the best possible writer he can be—warmed, brightened, flowering under the rocket summer of his work.

Amit Majmudar is a diagnostic nuclear radiologist who lives in Westerville, Ohio, with his wife and three children. The former first Poet Laureate of Ohio, he is the author of the poetry collections What He Did in Solitary (Knopf, 2020) and Dothead (Knopf, 2016) among other novels and poetry collections. Awarded the Donald Justice Prize and the Pushcart Prize, Majmudar’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Best of the Best American Poetry, and the eleventh edition of The Norton Introduction to Literature. Two novels are forthcoming in India in 2022: a historical novel about the 1947 Partition titled The Map and the Scissors, and a novel for young readers, Heroes the Color of Dust. He is also currently co-creating a graphic novel, The Kali Yuga Chronicles.