Library of America lays claim to another major twentieth-century writer and to a key figure in literary postmodernism with the arrival of Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories, a comprehensive edition of the innovator who can fairly be said to have revolutionized the American short story. Revered during his lifetime, Barthelme (1931–1989) has been an enduring influence on subsequent generations of writers (and avowed fans) like George Saunders and Dave Eggers, among others, making Collected Stories an opportunity for re-evaluation and rediscovery.

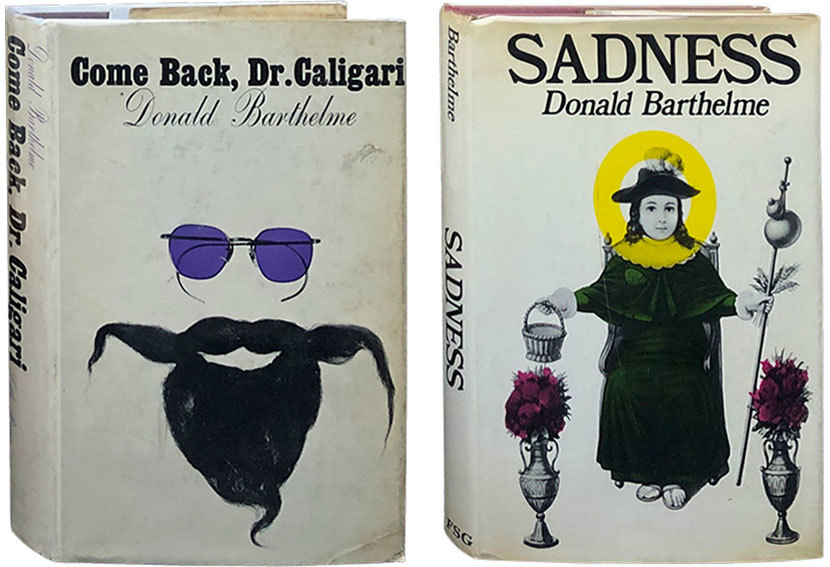

LOA’s Barthelme volume is noteworthy both for being the first complete edition of the stories—145 in all—and because it presents them as they were published in Barthelme’s original collections, from his 1964 debut Come Back, Dr. Caligari to the late pieces that appeared for the first time in his two retrospective anthologies, Sixty Stories (1981) and Forty Stories (1987).

The book’s editor is Charles McGrath, a writer at large at The New York Times and the former editor of The New York Times Book Review as well as deputy editor of The New Yorker. McGrath also edited the Library of America volume John O’Hara: Stories in 2016. Via email, he answered our questions about what makes Barthelme such a distinctive writer of short fiction.

Library of America: LOA’s editorial strategy in Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories is to reprint the stories in their original collections. You have said that Barthelme thought of each of those books as a specific work of art. How do the individual collections differ from one another, and what is he trying to do in one that he isn’t doing in another one from a few years earlier, or a few years later?

Charles McGrath: There’s not a huge difference from collection to collection, and it’s probably too much to say that there’s an arc of development. Barthelme hit the ground running—his style was there from the beginning and it’s pretty much the same at the end. But the first collection, Come Back, Dr. Caligari, is maybe a little more off-putting than the rest. He’s announcing himself as someone new and different, and some of the stories, at the beginning especially, can be hard going. For that reason, I suggest in the introduction that readers new to Barthelme skip to Sadness, his fourth collection and one of his best, and then double back.

For the most part, the later collections are a little sparer than the early ones—sparer in the writing, I mean—and maybe a little sadder as well. He was always funny, but he found less to laugh at.

LOA: The unusually capacious end notes to Collected Stories reveal the extraordinary breadth of Barthelme’s cultural references. How much does a reader’s enjoyment of these stories depend on understanding/recognizing these allusions?

McGrath: The notes were great fun to do, thanks in large part to the Internet. Had it been around fifty years ago, I wouldn’t have dropped out of graduate school, and I’d be a professor somewhere now—and would never have got to know Don B.! His range of references and allusions was even greater than I remembered, and I’m going to bet that the number and variety of the notes might be something like a LOA record. But I think you can happily read most of the stories without picking up on every single nuance. I hope so, anyway. There’s nothing worse than having to flip to those back pages all the time—though, thank goodness, LOA gives you that little ribboned bookmarker.

LOA: As you explain in your introduction, Barthelme was keenly alert to the momentous innovations that were galvanizing cinema, the visual arts, and so many other media in the 1960s. How are these influences he absorbed from the wider culture evident in his short fiction?

McGrath: They’re everywhere—in all those references and allusions we just talked about, and also in the form of the stories themselves. They borrow techniques from the movies, the visual arts, and even jazz and pop music: jump cuts, collage-like layering, riffs and solos. He’s at great pains to remind you that you’re not reading your grandfather’s short story.

LOA: Can you comment on Barthelme as a social critic, and why this aspect of his work seems to be under-recognized? We have in mind, for instance, the remarkable 1967 story “Report,” a scathing response to not only the Vietnam War but the technocratic mindset that made the war possible.

McGrath: Probably because—in the fiction, anyway—most of the social criticism is disguised. “Report” is in a way uncharacteristic in its overt criticism. More typical is a story like “The Indian Uprising,” also a critique of the Vietnam War, though it takes a while to figure it out, and readers a generation from now may not pick up on that at all. I don’t think that’s such a bad thing. He was writing fiction, not agit-prop. But he was, nevertheless, an impassioned social critic, and where you really see it is in the many unsigned Notes and Comment pieces (editorials of a sort) that he wrote for The New Yorker during much of his career. Both the war and Nixon made him apoplectic.

LOA: An admiring review of LOA’s volume that just appeared in The American Conservative argues that Barthelme is insufficiently appreciated as a Catholic writer. Is there a religious or spiritual dimension to his work, underneath the surface hijinks?

McGrath: I just read that piece, which seemed to me very smart and makes a point I hadn’t thought of. Don was not a believer—he was ardent in his agnosticism. But he was raised a Catholic, went to Catholic schools (until his high school accused him of plagiarism, on the ground that nobody his age could write that well), and I now think he retained a sort of Catholic sensibility. A lot of his late stories take the form of Q and A’s, but if you look at them closely, they’re really catechisms. If guilt, penance, forgiveness are Catholic preoccupations—well, there’s plenty of all three in Barthelme. His greatest theme, you could say—he’s sometimes sad about it, sometimes funny—is what fallen creatures we all are.