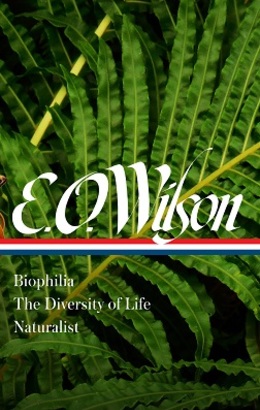

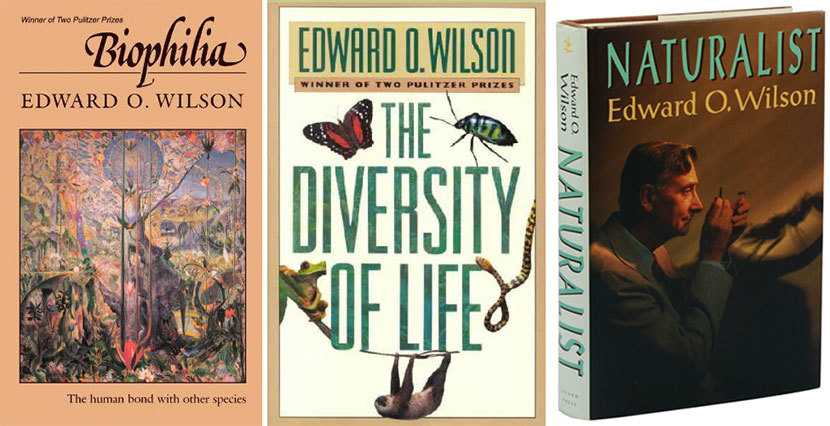

With the just-published Edward O. Wilson: Biophilia, The Diversity of Life, Naturalist, Library of America brings together three environmental classics by the world-renowned biologist who has twice won the Pulitzer Prize. The essays collected in Biophilia (1984) offer Wilson’s reflections on the manifold meanings of wilderness, while 1992’s The Diversity of Life—filled with little-known creatures, unique habitats, and fascinating ecological detail—is both a sweeping tour of global biodiversity and a prophetic call to preserve the planet. Wilson’s autobiography, Naturalist (1994), follows him from his outdoor boyhood in Alabama and the Florida panhandle to the rainforests of Surinam and New Guinea, from his first discoveries as a young ant specialist to his emergence as a champion of conservation and rewilding.

Taken together, and reissued at a time of inescapable climate change and mass extinction, these three works illuminate the evolution and complex beauty of our imperiled ecosystems and the flora, fauna, and civilization they sustain.

The book’s editor, David Quammen, is himself one of America’s most prominent science and nature writers. His more than a dozen books include The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinction (1996), Spillover: Animal Infection and the Next Human Pandemic (2012), and, most recently, The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life (2018). From his home in Bozeman, Montana, Quammen answered our questions about Wilson.

Library of America: With this volume, E. O. Wilson joins a long and distinguished lineage of science and nature writers in the Library of America, including such names as Aldo Leopold, Loren Eiseley, and Rachel Carson. How does Wilson extend this tradition, and what does he bring to it that’s new?

David Quammen: Wilson is unique among American biologists in his career of combining astute and transformational theoretical thinking with two other elements: extraordinary service drawing public attention to the crisis for biological diversity on Earth, and elegant popular writing. He is a towering literary figure as well as a vastly influential and controversial contributor to several different branches of biology—namely biogeography, sociobiology, and understanding of the social insects.

LOA: E. O. Wilson: Biophilia, The Diversity of Life, Naturalist constitutes the first half of Library of America’s planned two-volume Wilson edition. How did you choose from among Wilson’s more than thirty books, and what’s the rationale for grouping these three together in the first volume—is there something that makes them a cohesive unit?

Quammen: These three books fit naturally together as a first volume of the LOA Wilson because all three focus on the subject of biological diversity and also contain some of Wilson’s most personal (and beautiful) writing. They are engaging, embracing, confiding, and humane. In other words, they are Ed.

The second volume, comprising On Human Nature, Consilience, The Social Conquest of Earth, and selections from Sociobiology, will be Dr. Wilson at his most daring, conceptual, and controversial. It will be electric with challenges to comfortable assumptions and conventional wisdoms.

LOA: In his essay “The Right Place,” included in Biophilia (1984), Wilson writes: “Field research consists of hard physical work broken by moments of happy surprise.” I wonder if we can talk about some of Wilson’s field experiences over the years. What kinds of “hard physical work” were involved? What were some of the surprises?

Quammen: Hiking off-trail through tropical forest, especially if you’re pausing often to get down on your knees and investigate microhabitats to find insects, is definitely “hard physical work.” Ed Wilson has done plenty of that—and in his early career, as a young assistant professor at Harvard, he made some epic field journeys that are nicely recollected in Biophilia and Naturalist. In 1954 it was a long collecting trip to Melanesia, including the big island, New Guinea, and a number of little ones, that gave him opportunities to punctuate sweaty bushwhacking through deep forest and thorny thickets with moments of discovery and surprise. He recounts in Naturalist, for instance, slogging five days on foot across eastern New Guinea, and upward, to the central ridge of the Sarawaget Mountains. Among his rewards for such effort was his discovery of “discordant patchiness” of species distribution—hike just a few hundred meters, and the fifty ant species you find are mostly different from the fifty species resident where you started. This important principle is now known as gamma diversity.

On a later field trip, to Surinam in 1961, he walked out of camp and busted open a decaying log, a good tactic for finding ants. With his hand lens he inspected the ants he found, pale yellow and almost eyeless, and recognized what had previous been thought to be the only true “cave ant” in the world, known solely (until then) from underground caverns. Here it was as a topside forager.

That was a small, particular discovery, not a new ecological principle, but it pleased him—and it pleases the reader, as he relates it in Biophilia. It reminded him, as he reflected on it, back in camp, that for a scientist like him, a scientist of tiny creatures and big ideas, “it is possible to spend a lifetime in a magellanic voyage around the trunk of a single tree.”

LOA: Though a conservation ethic is evident in the first book here, Biophilia, by the time of The Diversity of Life (1992), Wilson is much more openly an environmental advocate. For the benefit of newcomers, can you shed some light on the development of Wilson’s thinking in this area?

Quammen: Biophilia, first published in 1984, was the heralding horn-blast of Ed Wilson’s entry upon the crucial, vast subject of how humans—all humans, not just nature-loving souls—relate to the rest of the natural world. It appeared at about the same time that other biologist-writers began issuing clarion warnings of the extinction crisis—writers such as Norman Myers (The Sinking Ark, 1979) and Paul and Anne Ehrlich (Extinction, 1981). It expanded their warnings into a psychological dimension. The Diversity of Life, coming eight years later, was encyclopedic rather than lapidary, and established Wilson in the role he has held since: as the world’s foremost public spokesperson on the subject of biological diversity and the importance of cherishing and preserving it.

LOA: The writer Richard Louv coined the phrase “nature-deficit disorder” to describe one of the problems of modern childhood—kids spending so much time indoors and in front of screens that they may actually end up with behavioral problems and never care much about “the environment” except as a vague abstraction. What does Wilson’s autobiography, Naturalist (1994), tell us about how young naturalists are made?

Quammen: Naturalist is like a bildungsroman for the surprising young lad who could grow up to revolutionize the field of theoretical biogeography, consolidate the field of sociobiology, and elevate global concern about biological diversity. Except of course that it’s a real-life story, not a novel. The most wonderful and telling thing about it is that Wilson chose to title his autobiography Naturalist and not Biologist. That choice reflects his awareness of the fact, still true, that a life devoted to the study, understanding, and appreciation of non-human life in all its forms is not likely to begin in a classroom. It’s not likely to arise merely from books, let alone screens. It’s a sort of devotion, an instinct like morality, that grows from green shoots. Not every great biologist begins as a kid with a butterfly net and a desire to turn over rocks in clear-running brooks to see whether the miracle of a salamander might lie underneath. But many of them do. And for other young people too, those who will never be biologists, but who will make crucial adult decisions about their individual consumption of resources, their reproductive contribution to human population size, and as citizens their responsibility for the stewardship of wild places, a childhood without exposure to woods, creeks, ponds, swamps, rocky ocean coastlines, snakes, spiders, giant moths, cicadas, starfish, limpets, owls, hummingbirds, foxes, deer, and the occasional bear glimpsed at a respectful distance—that indoor childhood will be an arid preparation for life on a planet that we hope will remain blue and green.

LOA: How has Wilson been an inspiration in your own work? You’ve generously acknowledged The Theory of Island Biogeography, his 1967 book co-written with Robert A. MacArthur, as a personal touchstone, but we’re curious to know whether and how his subsequent writing has been an influence.

Quammen: Ed Wilson’s body of work has been enormously important and inspirational to me personally because biology, for me, has always been the career road not traveled. I spent a childhood in the woods and the creeks, much like he did, and I thought of converting my fascination with nature into a profession. But instead I followed my other early instinct and love, into writing. At first, I was a novelist, working in ways and on subjects entirely separate from the natural world. Ed was one among a very small group of writers (including Haldane, Eiseley, Fabre, Lewis Thomas, and a few others) who showed me, when I began reading nonfiction, that nonfiction could be art, and that biology could be the substance of that art.