In February 1933, just two days after the burning of the Reichstag, the German publisher Kurt Wolff and his second wife Helen fled their homeland. The grandson of converted Jews, Wolff saw the writing on the wall. But it was more than bloodlines that imperiled him. Twenty years earlier he had established Kurt Wolff Verlag, one of the premier publishing firms in Germany. Wolff had an uncanny eye for discovering modernist and expressionist masterpieces, publishing works by Franz Kafka, Franz Werfel, Heinrich Mann, and Joseph Roth, among other writers, building an avant-garde catalogue now deemed degenerate by the new order.

Less than a decade later, in the fall of 1941, after perilous exiles in Fascist Italy and Vichy France, Kurt and Helen were able to secure visas from the Emergency Rescue Committee to travel to the United States, where, in New York, they soon established Pantheon Books, an imprint that became a leading publisher of international literature. Suddenly alienated from the world he had known, Kurt Wolff defined a new mission for Pantheon: “to present to the American public works of lasting value, produced with the greatest care and quality. Our editorial concept is to help spread knowledge and understanding of the essential questions of human life and culture.”

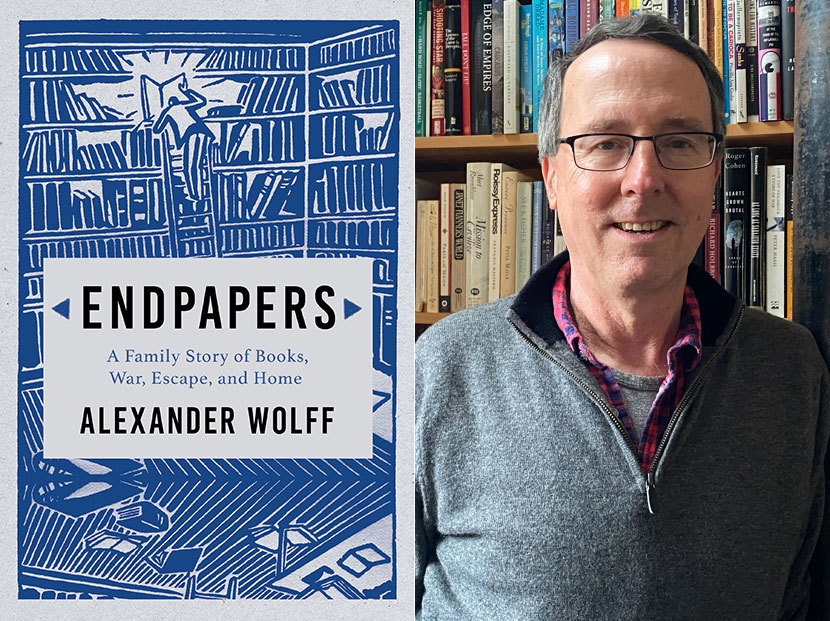

We have a special affinity for that mission at Library of America, as we do for Kurt Wolff’s grandson, sports journalist Alexander Wolff, who edited our 2018 anthology Basketball: Great Writing about America’s Game. Alex has written a remarkable and riveting accounting of his family’s experience of the calamitous twentieth century, Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape, and Home, just published by the Atlantic Monthly Press. The product of a year spent in Germany researching his family’s past, it follows not only his grandfather’s journey into exile, but also the trials of his Jewish forebears, the implications of the corporate wealth brought by Kurt’s first marriage to Elisabeth Merck, whose family’s pharmaceutical firm was entwined with the Nazi regime, and most profoundly, the fate of Kurt and Elisabeth’s daughter Maria and son Nikolaus, Alex’s father, who were left behind to come of age under Hitler.

We’re very grateful that Alex could take some time to visit with us from his home in Vermont.

Library of America: Alex, thanks. This is an extraordinary, multi-layered story and we can only hint at its richness here. But let’s start with Kurt, who died when you were just six. Do you remember how you first came to have a sense of who he was as a public figure, other than as your “opa”? Was his legacy as a publisher, as a man of the arts, a source of pride in your home growing up?

Alexander Wolff: My parents told stories as far back as I can recall about Kurt’s insistent way of sharing his enthusiasm for fine things. Such as gleefully pouring a glass of wine when you’d really rather not have one, for instance. It would be a while before I’d learn of my grandfather’s literary career and roster of writers. But I was eventually able to draw a line from Kurt’s avowed tastes to his need to foist them on others, which is essentially what a book publisher does.

His widow, my step grandmother Helen Wolff, published for another thirty years after Kurt’s death, so she made the bigger mark on me—her authors included Günter Grass, Umberto Eco, and Georges Simenon, and I actually saw those names in shop windows and on bestseller lists. Helen of course told me stories about Kurt, as my mom and dad did. But for the most part my grandfather remained mythic to me, shrouded by the past, a larger-than-life charmer and grand seigneur. Which probably helped account for my wanting to explore his life and times.

LOA: Your grandfather’s decision to flee Germany seems in retrospect to have been characteristically percipient. But your father Niko, then twelve, and his fifteen-year-old sister Maria remained with their mother and stepfather in Munich, and eventually Niko would find himself conscripted into the Reich Labor Service and then into the Wehrmacht. Both siblings would be exposed to the war’s horrors: Niko, serving first on the Eastern Front and then in the final desperate struggles in the west in the Ardennes, and Maria, enduring the unrelenting Allied bombing of Munich and Freiburg. Your grandfather, from the safety of America, would come to view the war, and the question of the German people’s responsibility for it, in a way different than his daughter, and in one of the most compelling sections of your book you record an exchange of powerful and eloquent letters on this subject between Kurt and Maria. To what extent were they able, ultimately, to bridge this divide?

Wolff: Being the younger of Kurt’s two children by his first marriage, and having interests that ran toward technical things, my dad had an easier time carving out an identity distinct from his father than Maria did. I think Kurt came to admire the way Niko started over in America, quickly becoming fluent in English (which Kurt never fully did) and making a prosperous and happy life. Maria, on the other hand, craved Kurt’s approval and attention in a way my father never did. My aunt loved art and literature and hung on what her father had to say. To read some of her writing is to hear the voice of someone who felt abandoned, who’s desperate to get her father to understand what she has been through. I do think Maria was able to convey to Kurt how she and her infant son and the German people at large had suffered.

But of course Kurt had his own harrowing story of exile and escape, and the suffering of all parties could be traced back to the same source—Nazi Germany. The irony is that, in the early Sixties, Kurt left Pantheon after a falling out with its board and moved back to Europe, only to die there in 1963 in a freak accident. A few years later Maria relocated to Manhattan, where her husband had been put in charge of the Goethe House on Fifth Avenue. It seems that, after the war, Kurt and Maria were fated never to spend sustained time near each other. But no one in my family embodied Kurt’s aesthetic and wit and manière de vivre more than Maria.

LOA: Eventually, after some time in an American POW camp, your father, with an assist from your grandfather, was able to come to America on a student visa. And if Kurt was only ever an émigré here, still tethered to the high culture of the Old World to which he would eventually return, Niko was an immigrant in the deepest sense: hard-working, civic-minded, and patriotic. “I could have kept studying in Munich and worked for Merck and had a happy, easy life,” you quote your father as saying. “But I wanted to get out from my past.” By seizing the opportunity to start over in America your father was able to create a new life, a new world of possibilities for himself and, ultimately, for the family he would make here. But at what cost, do you think?

Wolff: My dad was always hugely grateful to have been able to emigrate and become a U.S. citizen. To him it might have been a case of the scales balancing out after having the first third of his life chewed up by the German catastrophe. To live out the rest of his adult life in a Germany subsumed by denial or shame would have been stultifying and debilitating. Think of the novels of W. G. Sebald, and the way silence sits like a weight on my father’s generation. Even though he was no great philosopher, my dad knew this, I think—he told me he had left because Germany “had too much baggage.” And while I make a point in the book of how resolute he was in looking forward, not back, on those occasions I asked him about the war and the Third Reich, he did respond, as if it were part of his fatherly duty.

I spend a chapter on a cruise we took together down the Danube in 1996, my chance to ask him about his youth and the war. It took some effort for me to pose the questions, but when I did, he didn’t dodge them. “Maybe you’ll write about this someday,” he said at one point, watching me take notes. When I embarked on this project after his death, I took comfort and strength from those words. I don’t know if he ever felt a need to atone for what he’d been conscripted into doing as a soldier of the Third Reich. But I’m struck by how he became involved in a group devoted to U.S.-Soviet relations during the height of the Cold War. If he hadn’t been involved in the invasion of the Soviet Union nearly a half-century earlier, I’m not sure he would have taken up that particular cause. The past seemed still to be lurking inside him somewhere.

LOA: If there is a prevailing theme in your book it might be this idea of responsibility: for whom and for what are we responsible in this life, as parents and children, as citizens and soldiers, even as descendants. And here, in this last regard, the story of the Merck side of your family takes on special import. Viewed from one perspective, the notion that we should bear a moral responsibility for the actions of those who came before us can feel somewhat unjust. And yet if the last year has reminded us of anything it is how heritable are the structures of power and privilege. How did your research into the records of Merck’s complicated history affect your sense of the trajectory of your own life?

Wolff: My father never talked about Merck’s implication in the Third Reich—perhaps because he didn’t know the full extent, more likely because he didn’t want to burden my sisters and me with that baggage he had left behind when he emigrated in 1948. But here’s where I feel I should tip my hat to contemporary Germany, and to Merck KGaA, the family firm still headquartered there. Much of what I discovered about the company founded and run by my father’s mother’s relatives and ancestors—that it fired Jewish employees, who were then murdered by the Nazis; that it supplied drugs to Hitler and raw materials to the Nazi war effort; that my dad’s favorite uncle was a Nazi Party member—is due to the unfettered access I had to company archives, as well as an independently written corporate history that Merck recently commissioned. This is what the Germans call Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung, or “working off the past,” a process that a striking breadth of German society has engaged in.

My takeaway from all this risks sounding Pollyanna, but it’s what I’ve got: How do we avoid ever getting to that point where anyone is forced to choose between serving a murderous regime or being branded a traitor to one’s country? Only by exercising our voice and our vote at every opportunity. As Grass said, “Politics is too important to be left to the politicians.” So as my wife and kids will tell you, I’m a Johnny One Note about civics and political engagement, an obsession I picked up from my father. As for debts that fall to subsequent generations, I have a much more acute sense of what my many privileges rest on. I’m excited to be collaborating with other family members on a transnational initiative in Helen Wolff’s name. It’s still in the early stages of development, but would fund scholarships for at-risk female writers from conflict areas.

LOA: At one point in Endpapers you quote Hannah Arendt, a friend of Kurt and Helen’s: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience), and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought), no longer exists.” (Having recently published Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life and The Paranoid Style in American Politics in the Library of America series, we have been reflecting on these issues quite a bit of late.) Coinciding as it did with the early part of the Trump administration and the migrant crisis in Europe, your year in Germany gave you a special perspective on the course of politics and culture in both countries. What did you learn about how we and they have grappled with the past, or failed to?

Wolff: If I’d wanted to keep my focus on Germany and German history alone, it soon became impossible. Charlottesville took place four days after I arrived in Berlin, and Trump was dominating the discourse in Germany at the same time Angela Merkel was modeling what the world had once associated with the America that welcomed my grandfather and father: denouncing Nazis and Nazism; welcoming immigrants and asylum seekers; encouraging the spread of democracy around the globe.

The late German journalist Sebastian Haffner, in Defying Hitler, describes the conditions that allowed Nazism to take root. But in letters I found, my ancestors were striking the same notes. It was astonishing to read Kurt, in a 1931 letter, describing in Germany “a doomsday mood that has become a common mass psychosis.” And to discover, in a letter to her brother in February 1933, that Helen, a half-dozen years before Haffner’s prescient memoir, writes: “Those for whom normalcy is insufficient always create chaos and destruction.” I arrived in Berlin determined not to draw lazy comparisons between Germany in the 1930s and America in the late 2010s. It would be irresponsible to do so, I’d tell myself. And then the slow roll of events between 2017 and 2019 seemed to say: it would be irresponsible not to do so.

Alexander Wolff spent thirty-six years on staff at Sports Illustrated. He is author or editor of nine books, including the New York Times bestseller Raw Recruits and Big Game, Small World, which was named a New York Times Notable Book. A former Ferris Professor of Journalism at Princeton, he lives with his family in Vermont.