Rollin Lynde Hartt (1869–1946)

From The American Stage: Writing on Theater from Washington Irving to Tony Kushner

Any melodrama of a century ago “wants not dramas but scenes,” wrote the journalist and preacher Rollin Lynde Hartt at the time, and each one was “peopled with characters who have little hesitation about making scenes.” Hartt, unlike many of his colleagues in the ministry (who were forceful in their condemnations), viewed such extravagant productions as mirrors of the lives of the working-class people who attended them in droves, and his 1909 book The People at Play examined vaudeville, melodramas, and other forms of popular culture.

Although he occasionally wrote as if he were an adventurer on safari, his fondness of—one might even say, passion for—“lowbrow” theater comes through in his chapter on melodramas. “Tepid, anæmic, and neutral-tinted by comparison, is our aristocratic drama, though the poor thing can’t help it. We bring to the theatre a fastidiousness that precludes the grander flights of art.” His essay, which is uproariously funny in places, describes scenes and actors from the dozens of tearjerkers, thrillers, and farces he had seen over during the first decade of the twentieth century—and he had obviously seen several of them more than once.

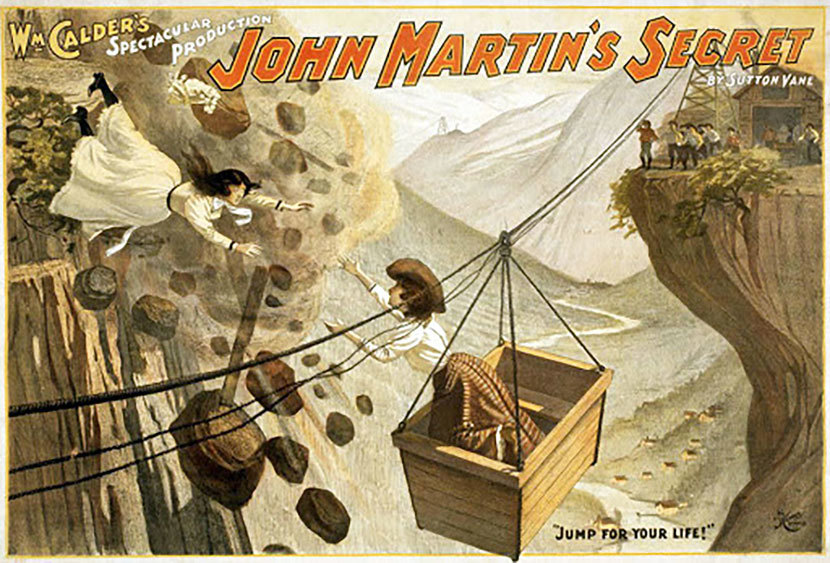

With titles like A Working Girl’s Wrongs; The Great Train Robbery; Red-Handed Bill, the Hair-Lifter of the Far South-West; Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model; and John Martin’s Secret: A Tale of the African Diamond Mines, the plays were universally formulaic and often incoherent: “The more you watch the thing, the more it is borne in upon you that a melodrama, far from being a play, is merely a vaudeville,—a string of hair-lifting playettes, with comic specialties interspersed.” What Hartt’s essay shows, however, is that the plays were nothing more or less than the transformation of the audience’s everyday melodramas into pure entertainment. We present it here as our Story of the Week selection.