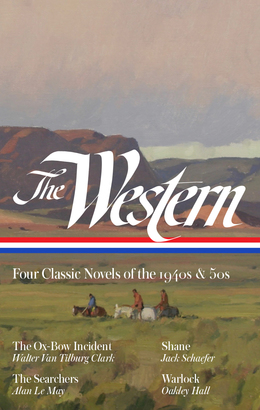

One of the most eagerly awaited entries in the Library of American series arrived earlier this year with the release of The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s & 50s, which collects four classic contributions to the quintessentially American genre.

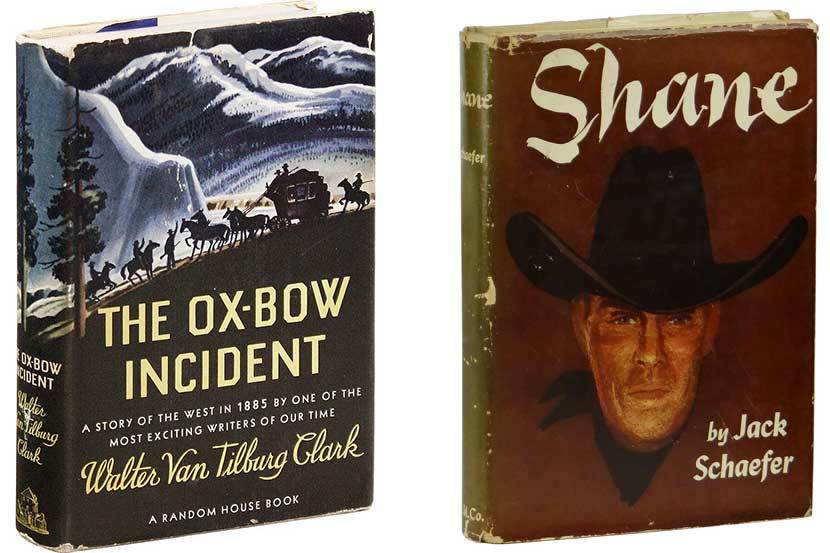

Famous for the movies they inspired, Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s The Ox-Bow Incident (1940), Jack Schaefer’s Shane (1949), Alan Le May’s The Searchers (1954), and Oakley Hall’s Warlock (1958) combine narrative sweep and thrilling exploits with a measure of psychological nuance and social commentary that may surprise readers who know only their Hollywood adaptations.

The volume’s editor, Ron Hansen, is himself a distinguished practitioner of Western and historical fiction, as the author of Desperadoes (1979), The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983), and more recently The Kid (2016), a reimagining of the life of Billy the Kid. In addition to nine novels, Hansen has also published two story collections and two volumes of essays and teaches at Santa Clara University. Via email, he answered our questions about The Western earlier this fall.

Library of America: The Western was a dominant cultural phenomenon in the middle of the last century, in books and magazines and on radio, film, and TV, both a hugely popular entertainment and fertile literary ground for playing out America’s postwar concerns. What is it about the Western? Why do we continually return to it?

Ron Hansen: The Western combines a distinctly American mythology with a clarity of plot and exposition delineating good and evil, right and wrong, in ways that can be simplistic but are frequently complex, diverting, and satisfying. Although they are generally escapist reading, the four books included in this volume are rich with riveting sociological and psychological questions that make them hard to put aside, that keep their stories churning in one’s mind.

LOA: In an admiring review of this volume for The Wall Street Journal, Stephen Harrigan said that “there’s still something fresh and surprising to be found in these books.” For people who know only the movie versions of these novels, what are some of the surprises waiting within these pages?

Hansen: The freshness of these novels lies in their grand but no longer available settings and in the way the characters speak in an argot that was once familiar but is now seldom heard. The surprises have their origin in fully developed characters who depart from the easy fabrications of the nineteenth-century dime novels and present people who are multifaceted, self-reflective, and yearning.

LOA: At first glance, Jack Schaefer’s Shane is a work of overt mythmaking: the definitive depiction of the lone gunslinger who rides into town and dispenses rough justice. But your introduction hints at a level of psychological complexity that may elude some readers caught up in its fisticuffs and riveting gunplay. Can you talk a little bit about how Shane is a subtler novel than it may initially appear?

Hansen: Hardly ever in a Western have I found the Freudian subplot of the Starrett couple, a husband and wife who seem “unequally yoked,” and have a competing fondness for the attractive stranger who has happened into their lives. Added to that is Joey, a boy who idolizes Shane and, in our current social climate, seems to be groomed by him. While rather subtly presented in the novel, the film version makes the situation so much more overt and, well, weird that my undergraduates laughed at scenes that Schaefer intended to be far more solemn.

LOA: Oakley Hall’s Warlock (1958) introduces both a new note of satire and moral ambiguity to the Western genre. How is Warlock reflective of the Cold War environment that produced it, and does Hall anticipate the changes in sensibility that led to the revisionist or “dirty” Westerns of a later era? (We’re fascinated that Warlock’s most prominent fans include Thomas Pynchon and Robert Stone, two novelists notably attuned to the countercultural energies of the 1960s.)

Hansen: Oakley Hall was both raffish and wise; he recognized that nineteenth-century Tombstone and those other Old West towns that Warlock limns are completely different and exactly the same as our cities in the Cold War period. And that “exactly the same” is where revisionism comes from. There’s a sense of Oakley winking and chuckling throughout the construction of a narrative that is a serious commentary on our contemporary ways of being.

LOA: As you suggest in your introduction, The Ox-Bow Incident, Shane, and The Searchers owe some of their authority to the fact that the world of the frontier was still (just barely) within living memory at the time they were written. What might have been lost, and what was gained, when the Western novel subsequently became a kind of historical fiction?

Hansen: Old West heroes and villains were often mythical symbols or types. We’ve pretty much lost the joy in encountering them. Replacing that is a far more realistic, historically grounded novel that gives a far keener sense of the period simply because the milieus are unfamiliar and need to be more carefully imagined. Research has become important; reverie less so.