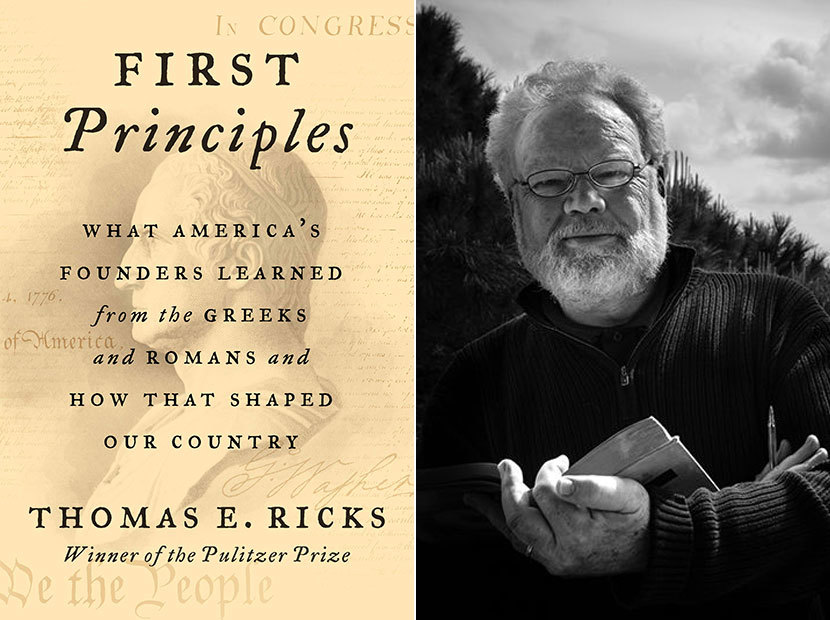

Our latest guest post arrives today from the historian, journalist, and commentator Thomas E. Ricks, whose new book First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country, is out this week from HarperCollins. The book arrives bearing praise from fellow historians Annette Gordon-Reed, who calls it “erudite and fascinating,” and Gordon S. Wood, who writes, “Ricks knows his subject well, and, equally important, he writes about it lucidly.”

First Principles required Ricks to plunge into the writings of America’s first four presidents—a sustained intellectual engagement he describes in the column below.

By Thomas E. Ricks

My favorite spot to read in the world is my rocking chair in our living room overlooking a small harbor on the Maine coast. My favorite books to read there are those published by Library of America. Often I will be concentrating on one of those little black volumes and will look out and realize that the tide has turned while I was immersed in words. For me, this chair by the window is the spot where the process of writing a book begins, in the notes I take as I consider what I have been reading.

Over the last three years I have read twelve Library of America books cover to cover. Most of these were for my current book project, titled First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How that Shaped the Country. A few more have been for my next book, which is still evolving.

I love almost everything about these Library of America editions. They are cleanly laid out, stark and readable. Each volume carries the implicit promise that it contains one thousand pages of the essential writings by the author in question. (Though I still wonder how the editor of the Thomas Jefferson collection got permission to stretch that to a fat 1,600 pages, especially given that Jefferson was a notably uneven writer.) After going through one of these volumes, I feel like I have been shown how a person wrote and thought, given a glimpse of their view of the world and of their particular and persistent concerns about it.

I even like the little ribbons for place markers. They’re an elegant touch. Most of the ribbons in my volumes are blue, with a few variations—John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, for example, both sport green pennants.

My only complaint about Library of America books is that they don’t leave me enough blank pages to take notes. I fill those thin, bone-white, desert-dry pages with questions, comments, exclamations and plans for further research. Sometimes my notes cover the empty front pages in the front, then jump to those in the back, and finally snake into the index pages. If you deciphered those thousands of scrawled notes and put them together, you would have something pretty close to a preliminary version of the first draft of the book I just wrote.

For example, I loved going through George Washington’s letters and orders during the Revolution. We see him at his lowest point, in late 1776, wondering if defeat is imminent. At the same time, we see him begin to adjust from a conventional offensive strategy to a defensive approach of avoiding big battles and wearing out the enemy, a shift that would prove crucial to the eventual American victory. This step enabled him to make better use of American militia forces, who often broke and ran when confronting British regulars in battle, but were adept at skirmishing with enemy patrols and foragers, especially when they were fighting in familiar fields and forests near their homes.

You get to know these people. When Washington writes that he is “mortified” or “pained,” watch out—he is struggling to restrain his temper, which could be titanic. Likewise, the energy of Alexander Hamilton’s prose style almost jumps off the page. Or, in the John Adams volumes, the man’s cranky honesty and abiding vanity are continuously evident. Much more than in reading a biography of Adams, his essential sourness comes through on nearly every page. Jefferson’s two sides are evident throughout—his breathy flirtations in letters to married women such as Maria Cosway and Angelica Church, and his candid friendship in writing to James Madison.

The sole exception in my readings of the last several years was with Madison. As I did my research, I came to admire him enormously, not just for his essential work on drafting the Constitution and then campaigning for its ratification, but also for the way he led the way in recognizing in the 1790s that political parties were inevitable and taking steps to respond to that situation. Yet his achievements and drive don’t seem to me to be reflected in the words he left behind. There are few memorable phrases in his writings. Gordon Wood, one of the finest historians of the early Republic, states that it is widely accepted that Madison was “the most astute, profound, and original political theorist among the founding fathers.” I agree, but for some reason, Madison was far more influential in shaping America than his written words would indicate.

There is one more aspect I love about these books. Because the paper is so thin and the dimensions are relatively small, they make great travel companions. I hate running out of reading material while traveling. Having a fresh Library of America volume in my bag makes sure that won’t happen. They slip easily into the side pouch of my ragged old black canvas Lands End attaché bag. In recent months I have turned to LOA editions of Mark Twain, James Baldwin, and others. Earlier this year, I spent most of a flight from Charlotte, North Carolina, to Bangor, Maine, introducing myself to the Library’s selection of Albert Murray’s nonfiction works. As we waited to take off, I began by poring through the chronology and then the index, marking sections I wanted to make sure I didn’t overlook. By the time I took a moment to look out the jet’s window, Cape Cod was beneath the starboard wing.

When they are stacked together, the sameness of the books in size, font, and feel gives me the sense of witnessing a great American procession. Okay, we have heard from Thomas Jefferson. But hey, look, here comes Albert Murray marching along. Let’s see what he has to say.

Thomas E. Ricks is the military history columnist for the New York Times Book Review and a visiting fellow in history at Bowdoin College. His most recent book is First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned from the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country, published this month.