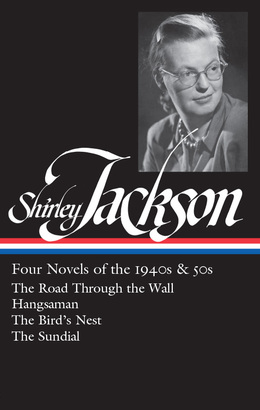

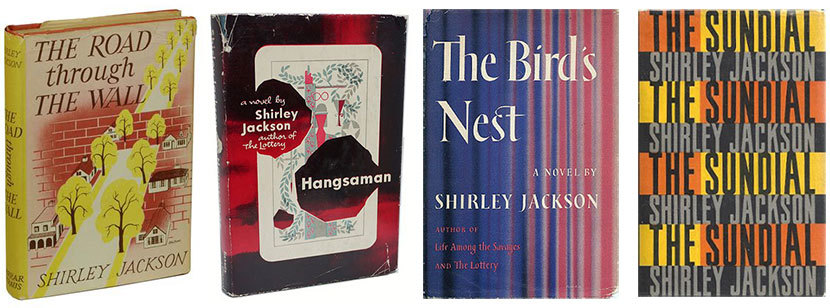

Just out from Library of America, Shirley Jackson: Four Novels of the 1940s & 50s collects the four books that launched the inimitable, all-too-brief career of the author of “The Lottery” and The Haunting of Hill House. The Road Through the Wall (1948), Hangsaman (1951), The Bird’s Nest (1954), and The Sundial (1958) are hypnotic, superbly controlled works of psychological unease that are no less disturbing for eschewing the supernatural elements of Jackson’s better-known later work.

Four Novels of the 1940s & 50s follows by exactly ten years Library of America’s first Shirley Jackson collection, Novels & Stories, which helped consolidate a major reevaluation of Jackson’s literary reputation and firmly established her as the twentieth-century heir to Poe, Hawthorne, and the Henry James of “The Turn of the Screw.”

The new book’s editor is Ruth Franklin, who played a major role in the Jackson revival herself with her 2016 biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, for which she received the National Book Critics Circle Award. A critic and frequent contributor to The New Yorker, Harper’s, The New York Review of Books and other publications, Franklin is also the author of A Thousand Darknesses: Lies and Truth in Holocaust Fiction (2011).

Library of America: Ten years after your influential New Republic essay and the first Library of America Jackson volume, the Shirley Jackson revival has become a full-blown renaissance that spills over into pop culture. While acknowledging the importance of your essay (and subsequent biography), what has changed in the culture so that Jackson is now widely considered a mainstream literary figure?

Ruth Franklin: The first Library of America volume was essential in bringing a wide range of Jackson’s work to the attention of those who might have previously only known a few of her stories or novels—including me! Now the four novels published in the second volume have been made newly accessible to the next generation of readers. While critics of Jackson’s era sometimes were frustrated by her refusal to be easily categorized by genre, I think today’s readers are much more open to the idea that writers can publish works across many genres—and that the boundaries between genre fiction and so-called literary fiction can be quite porous. (I have some further ideas about this that I expanded upon in my earlier blog post.)

LOA: At least a few readers coming to this collection will only be familiar with the later Jackson of The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle. What will they find in the new Library of America collection that might surprise them?

Franklin: One of the most striking features of Jackson’s work is that she never did the same thing twice. Each of her novels has its own distinct form and focus. The Road Through the Wall is an acidly satiric depiction of life in an upscale California suburb not unlike the one where Jackson grew up. Hangsaman is a coming-of-age novel, albeit an extremely unconventional one. The Bird’s Nest is based on a psychiatrist’s case study of a woman with multiple personality disorder, although Jackson takes that research into a surprising direction. And The Sundial, in which a wealthy family preps for an apocalypse that may or may not be about to occur, almost shades into science fiction. I’ll venture there’s something in each of these novels to surprise the reader who knows only the Jackson of psychological horror and suspense.

LOA: In lieu of haunted houses, etc., Jackson’s first two novels, The Road Through the Wall and Hangsaman, unfold in more quotidian real-world settings, a San Francisco suburb and a liberal arts college. How does Jackson still manage to create an atmosphere of pervasive unease against these ostensibly more familiar backdrops?

Franklin: The idea that horror can take place anywhere, even in the coziest, most familiar setting, is one of Jackson’s trademarks. Just think of “The Lottery,” in which a barbaric ritual plays out in a perfectly ordinary, nondescript American village. In those two early novels, everything starts out looking normal, but we get clues pretty quickly that while the setting is conventional, the people are not. It takes just a snippy comment from a nosy neighbor or a girl in the dorms to tip the landscape of the novel into something more unstable. Of course, even in Hill House and We Have Always Been Lived in the Castle, which use the uncanny in a more obvious way, there’s always a certain ambiguity about what exactly is going on. Critics are still unresolved on the question of whether Jackson intended the ghosts in Hill House to be actually supernatural or the psychological manifestations of Eleanor.

LOA: Your biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life is a powerfully argued case for Jackson’s body of work as “the secret history of American women of her era.” We’re wondering if you could talk a little about how Hangsaman and The Bird’s Nest, in particular, show Jackson as “a writer about the lives of women” (to borrow a phrase you used in a 2016 interview).

Franklin: Both of those novels focus intensely on a young woman in the throes of a psychological breakdown. In Hangsaman, first-year college student Natalie Waite feels her psyche gradually splitting in two, for no immediately obvious reason. The Bird’s Nest describes a woman suffering from multiple personality disorder, a diagnosis that was gaining in popular attention in the early 1950s, when Jackson wrote the novel.

But both books also speak in a much larger way to a culture in which the pressures women experienced could easily become unbearable. In many ways, women in the 1940s and 1950s (and later) had to wall off aspects of their character in order to survive. They had to behave conventionally at school at the cost of suppressing a wilder self, or to conform (at least superficially) to the social expectation to be a good housewife while harboring professional and creative ambitions. And in each of those books, the female characters are deeply misunderstood by the men who believe they are trying to help them—a situation that mirrors the profound confusion with which male critics greeted the novels in their time.

LOA: Several commentators have suggested that The Sundial is a comedy—if of a rather black, uniquely Jacksonian turn. Leaving aside her memoirs of motherhood, is humor an aspect of Jackson’s work that still goes underappreciated?

Franklin: Perhaps—although those motherhood memoirs have always had a lot of fans! There are definitely some very funny moments in The Sundial, in which some members of a wealthy family become convinced that the apocalypse is nigh and that they have been singled out as worthy of survival. (It is hard to imagine a group of people less suited to carry on the destiny of humanity.)

But there’s humor in just about all of Jackson’s fiction, even in The Haunting of Hill House, in which she breaks the tension of the haunted house by bringing in a hilariously funny character, an absurd medium who believes herself to be an expert in the supernatural but fails to perceive the ghosts that everyone else senses. In a lecture she gave regularly on fiction writing, Jackson called her technique “garlic in fiction”—grabbing the reader’s attention by using provocative little adjectives or images “to accent and emphasize.” Humor is one of the most effective ways in which she did that.