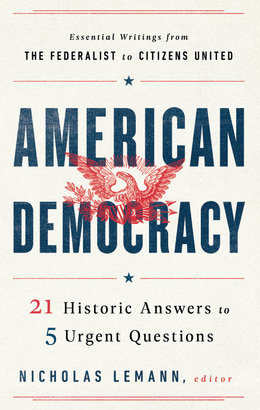

Just published by Library of America, American Democracy: 21 Historic Answers to 5 Urgent Questions offers a selection of key writings on five crucial questions confronting American democracy in the twenty-first century. Edited by journalist and historian Nicholas Lemann, the book collects well-known touchstones by George Washington and Frederick Douglass along with less familiar pieces by Jane Addams and Randolph S. Bourne for guidance and inspiration in our fraught moment. In the following excerpt from Lemann’s introduction, he sets out to define what constitutes a healthy democracy.

Democracy is a system. Because the word carries such a positive charge, people naturally assume that when, by their lights, the good guys are winning, it must mean that American democracy is in a healthy state. That is a temptation to be avoided: it mistakes an outcome for a process. It’s most useful to try to think about the condition of our democracy by pretending that we don’t know who’s on top at the moment. What, regardless of current events, should a high-functioning American system look like?

First and most of all, everyone should have an ironclad right to vote. Elections should be freely contested and conducted openly and fairly, and ballots should be counted accurately, without malfunctions or tampering. Outside of electoral politics, every citizen should have an inviolable set of basic rights, including the right to speak, write, and assemble freely, the right to due process of law, and the right to privacy. To say that these are the fundamental conditions of a good democracy doesn’t mean that they don’t have to be protected. They do not firmly exist everywhere in the United States today. But the underlying principles are straightforward.

It takes a greater effort to pay attention to the less obvious aspects of democracy, the ones that can be more difficult to embrace wholeheartedly and whose failings do not give rise to news coverage. One of these is representation. “The people” is an appealing construct. Originally, it would have been logistically impossible to empower the public to adjudicate every issue that arises. Now that is easier, so we should remind ourselves that we elect representatives in what is meant to be a spirit of trust that they can make specific decisions on their own, subject to our overall review when they run for reelection. Do we really want elected officials to be precisely attuned and responsive to overall public opinion on every issue, even in cases where the public opinion of the moment does not align with the right and necessary course for government? Politicians are representatives, not proxies. They need room to think about their constituencies’, and the country’s, long-term needs, and to protect the rights of minorities whose rights and interests the majority has a well-demonstrated capacity to ignore, especially at times when passions run high, such as national crises or periods of seductive demagogic leadership.

A healthy democracy requires a diversity of government institutions that hold each other in check, and also a set of strong civic institutions outside of government. Within government, we should be grateful that we have a bewildering welter of state, local, and federal entities, operating by different principles, and we should think of many-membered legislatures, not singular mayors, governors, and presidents, as the heart of democratic governance. In society, interest groups, political parties, an independent and varied press, and organizations that conduct policy research and advocacy are all essential actors in American democracy. It can be tempting to dream of a false ideal of democracy, one that either pursues the public interest without interference, or that always operates in accordance with the will of the people. This is a temptation to be avoided.

Politics is messy, politicians are often ignoble, interest groups are greedy, the press is sensational, parties are controlled by insiders. In the American system, all of that is a feature, not a bug. In the aggregate, an impure and varied democracy should produce spirited ongoing engagement combined with a shared commitment by all the players to abide by the outcome, at least until it’s time to try to achieve a different outcome next time around. It’s when everyone seems to agree, when one part of government (usually the presidency) seems all-powerful, and when the institutions outside government seem weak—as is the case now, for example, with America’s local news organizations—that we are right to worry about the health of our democracy.

There has never been a time when American democracy was in perfect shape. There have been times when that was the perception, at least of people at the top of the society, but in historical perspective those moments look like examples of willful blindness—to slavery and segregation, to the denial of rights to women, to unacceptable conditions for the poor and vulnerable, and to many other woes. It is essential always to allow for multiple and conflicting perspectives on the health of our democracy. Many of the selections in this book were written by outsiders who were motivated by their exclusion from the system.

This is our country. To be an American citizen is to bear a personal responsibility for improving American democracy. Everyone can do something. In deciding what to do, history helps. This book should serve as a spur to political reflection and action. The themes highlighted here—citizenship, equality, governance, money in politics, and protest—are long-running, essential flash points in American democracy, sources of vital debate, conflict, and creativity. They will still be flash points well into the future. The stakes are too high, and our opinions too varied, for any of them easily to be put to rest. Although the authors of the selections here are major historical figures, readers have a real commonality with them. All of them participated actively in American democracy. All of us can too.

Nicholas Lemann is Joseph Pulitzer II and Edith Pulitzer Moore Professor and Dean Emeritus of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University and the author of The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (1991), The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy (1999), Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (2006), and Transaction Man: The Rise of the Deal and the Decline of the American Dream (2019). He has been a writer and editor at Washington Monthly, Texas Monthly, and The Washington Post, a national correspondent for The Atlantic, and, since 1999, a staff writer for The New Yorker.