Author’s commitment to exposing injustices makes him more relevant than ever, argues biographer William Souder

“It has always seemed strange to me,” Doc observes in John Steinbeck’s classic 1945 novel Cannery Row: “The things we admire in men, kindness and generosity, openness, honesty, understanding and feeling are the concomitants of failure in our system.” Until he was well past thirty, Steinbeck enjoyed little in the way of success. His first book, the novel Cup of Gold, published in 1928, was remaindered almost before it was released, while the 1931 story collection The Pastures of Heaven sold only slowly despite good reviews. He would labor for five grueling years over the novel that became To a God Unknown (1933), never quite achieving the vision he had for it. Finally, in 1935, came Tortilla Flat, the first of a succession of books that would make Steinbeck one of the most enduringly popular American writers of the twentieth century, and a Nobel laureate.

As biographer William Souder shows in his engrossing new book Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck, this long apprenticeship in failure and frustration was the crucible in which Steinbeck’s extraordinary capacity for empathy was forged. Honesty, understanding, and feeling would become the hallmarks of his work, constants even as he experimented with a wide range of forms, styles, and emotional registers. They enabled him, in his greatest work, to give voice to the voiceless, exposing the corrosiveness of power and the perils of social injustice and ecological collapse. At the same time, they did not prevent him from being heedless and sometimes cruel to those closest to him.

The author previously of acclaimed biographies of Rachel Carson and John James Audubon, William Souder has brought us a Steinbeck uniquely relevant to this moment. As his new book goes on sale this week, he was kind enough to take some time to answer a few questions.

Library of America: Let’s start with your very evocative title. What was Steinbeck so mad about?

William Souder: It’s tempting to say “everything,” and let it go at that. Steinbeck was, in so many ways, America’s most pissed-off writer. In grade school, he befriended a classmate who was shy and got picked on. When he was asked why he wasted time with a boy nobody else liked, Steinbeck answered simply, “Because somebody has to take care of him.” Steinbeck could never abide a bully. Later, as a writer, Steinbeck filled his stories with people who were marginalized in a world he perceived in stark black-and-white.

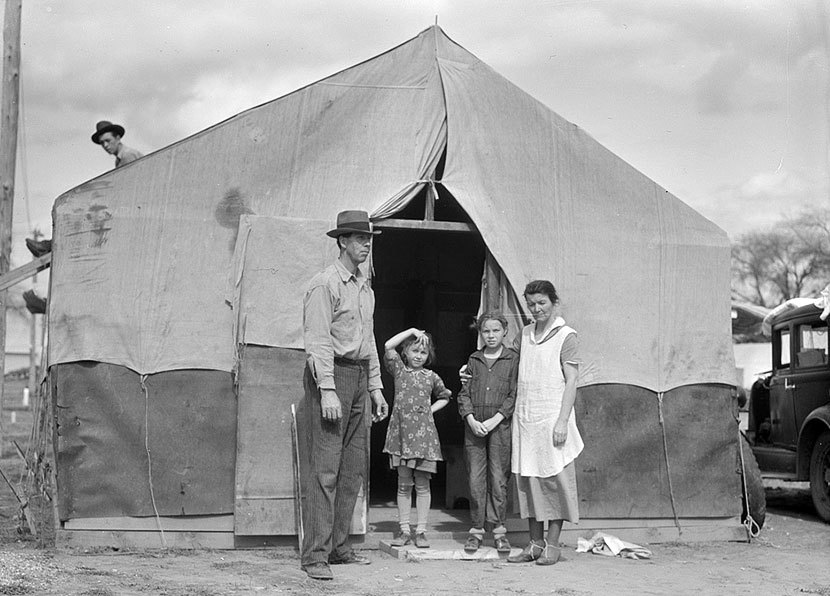

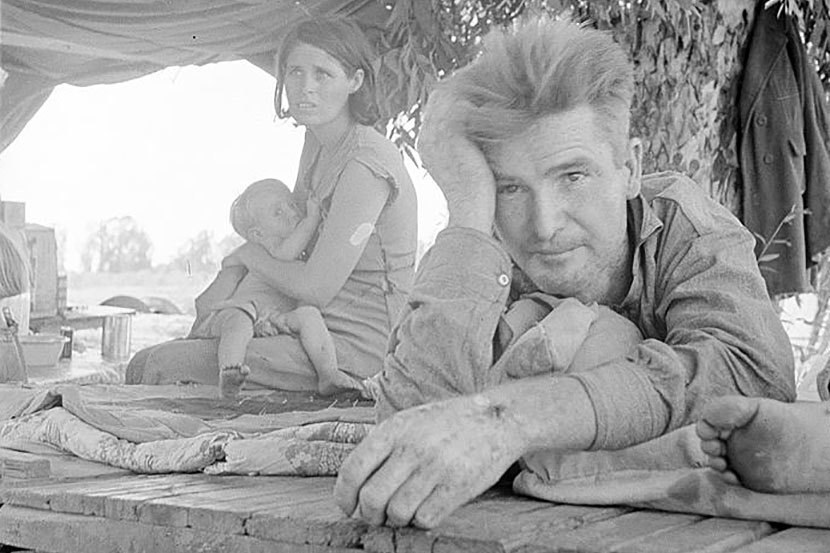

Steinbeck believed in good and evil, and he was convinced that morality was inversely proportional to your lot in life. Being good too often meant having little to show for it, he thought. This was especially true during the Great Depression, when millions of honest, hard-working citizens were dispossessed and displaced—many of them Dust Bowl refugees who ended up toiling for appallingly low wages in California’s farm fields. Steinbeck investigated the plight of the “Okies” and saw firsthand their squalid roadside camps, haunted by disease and starvation. The migrants were brutalized by the landowners who needed them and also despised them.

In 1938, Steinbeck, who thought the confrontations between the migrants and the landowners’ squads of vigilante enforcers could escalate into civil war, began work on a novel about the situation, focusing it on the oppressive tactics of the big farm interests. After a few months he tore up the manuscript and started over, telling the story this time from the point of view of the oppressed—a family named Joad from Oklahoma. Steinbeck, seething and telling himself again and again to work slowly and carefully, wrote The Grapes of Wrath, long since acclaimed as one of the greatest books in the American canon, in a rage and in a rush. He didn’t have to push himself. He was fueled by anger.

And that anger, that headlong storytelling that was heedless of the consequences—he liked making people uncomfortable—is present in many of Steinbeck’s books, maybe in some way in all of them. Even lighter-hearted works such as Tortilla Flat and Cannery Row are grounded in Steinbeck’s reverence for the guileless people the world tends to ignore or look away from. Steinbeck, who was often irritable and prickly in his personal life, couldn’t stop himself from making those people visible. He wanted the world to not just see the cruelties it was capable of, but to feel the pain. That’s why he remains relevant today, perhaps more than ever. The tragedy of forced human migration, the degradations of the natural world, and the grievous disparities between the haves and have-nots that are a seemingly intractable part of our lives would be all too familiar to Steinbeck. Times change, humankind’s problems don’t.

LOA: You use Steinbeck’s letters to great effect here. What do we learn about Steinbeck as a writer from his letters?

Souder: Steinbeck rarely let a day go by without writing a letter, usually several of them. They were often long, breezy accounts of his days and his work, whether it was going well or otherwise. Some he typed, others he wrote in his dense, microscopic cursive hand—though he experimented with his handwriting throughout his life. Letters were his way of keeping in touch, but they also often served as a warm-up for his working day. Or as a kind of exercise to keep his writing muscles in shape when a book was stalled. He was a generous and loyal friend, but was less kind to himself. Steinbeck’s letters often betrayed his belief that whatever book he was working on was no good. When he wrote of everyday things, life was sunny. When he spoke of his work it was all upstream in a bitter river of inevitable failure. Of course, he was usually wrong. Readers loved his books. That always took him by surprise.

LOA: Your account of the writing of The Grapes of Wrath—a 100-day endurance test that stands as a remarkable testimony to Steinbeck’s irrepressible will—is especially striking. Readers might be surprised by the significant role that Steinbeck’s first wife, Carol, played in the creation of his masterpiece. Can you say a little bit about that? Do you think this intense collaboration may have contributed to the dissolution of their marriage, not even a year after the book’s publication?

Souder: Carol’s role in that book can’t be overstated. As with all of his books while they were married, Carol was his muse and his first, most honest editor. She inspired him and then held him in check. With The Grapes of Wrath, Carol typed the manuscript from Steinbeck’s handwritten draft, correcting and amending it as she went, and matching her husband’s furious pace so that both versions finished at the same time. Steinbeck regarded all of Carol’s editorial changes as improvements, and he told everyone that The Grapes of Wrath was really Carol’s book.

But the fame and the royalty checks that were to come bore his name. I don’t think that, alone, strained their marriage to the breaking point. But Carol was brilliant and ambitious, and she knew that her political and literary instincts had helped to invent the John Steinbeck the reading public had fallen in love with. There are rumors, which may or may not be true, that Carol had an abortion at Steinbeck’s insistence that went wrong and left her sterile. Certainly Steinbeck’s affair with Gwen Conger, who would become his second wife, effectively ended his and Carol’s marriage.

My own thought is that their marriage was too small a vessel for two such epic personalities. Together they were a force of nature, like tectonic plates pressing against each other. It ended when the fault line finally gave way. But not before Carol had put something into Steinbeck that took hold, something that helped him write several of the most beloved and enduring books of his time, and that would figure, ultimately, in making Steinbeck a Nobel Laureate.

LOA: As you write, it was the great critic Edmund Wilson who noted in Steinbeck’s work “a preoccupation with biology . . . a tendency to present human life in animal terms.” One thinks, of course, of an explicitly biological book like Sea of Cortez, and unforgettable stories like “The Snake,” but clearly Wilson was getting at something deeper. Do you think it’s a useful key to Steinbeck’s work?

Souder: Wilson is my favorite Steinbeck critic, in part because he never got Steinbeck and in part because he totally got Steinbeck. Grudgingly, haltingly, resisting as best he could, Wilson admired Steinbeck’s work. And Steinbeck did have an organismal view of humanity—people are biological creatures. Wilson, on the other hand, thought biology was animalistic. For the birds, as it were. He didn’t think biology applied to people and only got in the way of their humanity. He convinced himself that Steinbeck had exceptional technical skill, but could not invent characters who were believably human, which might be the oddest complaint ever lodged against a major American writer. Here’s a thought experiment: Let’s find a dusty road in Oklahoma and stand Tom Joad in his cap and overalls up alongside the jowly, Princeton-educated Edmund Wilson, perspiring in his three-piece suit, and ask which one seems more real.

LOA: You devote a fascinating chapter to Steinbeck’s articulation in an unpublished essay of an “aggregation” theory of human behavior: “Men are not final individuals but units in the greater beast, the phalanx.” What was he getting at there? It gives new meaning to the memorably moving ending to Tortilla Flat. Like Rachel Carson, Steinbeck was captivated by the complex ecosystems of tidal pools. Do you think he anticipated something of Carson’s ecological insight when thinking about the ineluctable interconnectedness of individuals?

Souder: Steinbeck recognized that human beings acting in concert were capable of things that individuals are not, but, more importantly, that a group is a kind of superorganism, possessed of its own personality, instincts, behaviors, memories, tendencies, and capabilities. And he believed that this was the key to understanding why the world is sometimes the contrary way it is.

This idea almost certainly developed from, or was at least enabled by, conversations with his best friend, the marine biologist and tidal-zone expert Ed Ricketts. Like many mid-century field biologists—including, as you say, Rachel Carson in her books about the oceans and in her work for the Fish and Wildlife Service—Ricketts was caught up in the emerging field of ecology, in which organisms were increasingly viewed not in isolation, but as components within communities of interdependent living entities. Change the status of one species and all the others are affected. Steinbeck took the additional step of arguing that the community is more than the sum of its parts, and this helped explain why an army can do what one soldier would refuse to try, or how a village of pearl divers reacts as a single, communal unit when one among them has found a great pearl beyond believing.

Although I’m sure Steinbeck was mindful of this concept in many of his books—he said he kept discovering instances of phalanx in his work even when he hadn’t noticed it while writing—I’m not convinced it was essential. Or that it’s even a particularly interesting insight—except to the extent that it reveals Steinbeck’s regret that he was not a scientist like Ricketts. I think Steinbeck was never happier than on his collecting expedition to the Gulf of California with Ricketts, the basis for their co-authored book, Sea of Cortez. Even though Carol went with them when she and Steinbeck were barely speaking and would soon be divorced, Steinbeck was captivated by the sprawling communities of life in the tide pools they explored. Did it change the world if he plucked a starfish from a shallow puddle of saltwater? Did leaving their footprints on a beach alter the cosmos? Who could say? As Steinbeck later wrote, “None of it is important or all of it is.”

William Souder is an award-winning journalist and is the author of three books: Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of The Birds of America (2004), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; A Plague of Frogs (2000), which follows the investigation of outbreaks of deformed frogs across North America, and On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson, a New York Times notable book of 2012. He lives in Grant, Minnesota.

Dorothea Lange photographs above courtesy Wikiwand’s article on Steinbeck’s series “The Harvest Gypsies.”