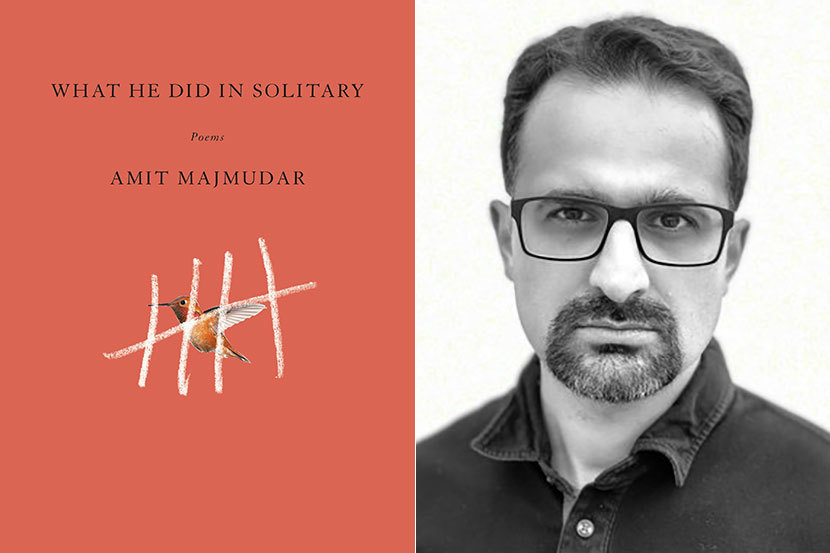

Our series of guest blog posts by contemporary writers returns with a contribution from Amit Majmudar, whose latest volume of poetry, What He Did in Solitary, is just out from Alfred A. Knopf.

Former Poet Laureate Billy Collins praised Majmudar’s previous collection, Dothead (2016), as “nothing less than a torrent of poetic inventiveness driven by . . . inexhaustible poetic energy.” Majmudar’s two novels, Partitions (2011), about the violent sundering of the Indian subcontinent in 1947, and The Abundance (2013), centered on an Indian American immigrant family in the Midwest, testify to his versatility across form and subject matter.

Below, Majmudar pays tribute to the contemporary classic that has become one of his personal touchstones.

Back in college, I used to unwind from my pre-med workload by wandering the university library’s stacks. Poetry, Literature in Translation, Religion. I didn’t really head into the Fiction region, except when I was on my way somewhere else. Why did I stop at that exact place in the stacks? Without pausing, without even fully reading the faded lettering on the spine, I slid out a novel.

Blood Meridian drew my hand to it. I still get goosebumps thinking about this moment, one of the most thrilling memories I have of my college years (all my adventurousness, even then, was literary). The only memory more thrilling was actually reading it.

Needless to say, I studied no more for the rest of the week. The Krebs cycle just couldn’t compare with those mercury-laden mules driven off the cliff in Chapter XIV.

The riders pushed between them and the rock and methodically rode them from the escarpment, the animals dropping silently as martyrs, turning sedately in the empty air and exploding on the rocks below in startling bursts of blood and silver as the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites and all its forms grouping below and racing in the stone arroyos like the imbreachment of some ultimate alchemic work decocted from out the secret dark of the earth’s heart, the fleeing stag of the ancients fugitive on the mountainside and bright and quick in the dry path of the storm channels and shaping out the sockets in the rock and hurrying from ledge to ledge down the slope shimmering and deft as eels.

The beaten-up, jacketless edition in the stacks gave me no indication I was holding a Western. That was perhaps for the best, since I had never read a Western before and, at the time, had no interest in that genre.

If all Westerns were half as good as Blood Meridian, I would read nothing else. No one in the genre or anywhere else does, or can do, what McCarthy does with the language in Blood Meridian. I suspect I love this book because it stimulates the poetry-reading part of my brain. I don’t think there’s a book of poems published in the 1980s whose verbal artistry I respect as much as McCarthy’s in Blood Meridian, published in 1985, the meridian of the decade.

McCarthy’s masterpiece does what almost all masterpieces do: It originates in a preexisting genre and transcends it. The collection of conventions that define a genre seem to be the necessary substrate of literary permanence. Individual greatness doesn’t come out of nowhere; that’s just how writers flatter themselves. It comes from the collective.

Moby-Dick arises as Seafaring Tale, whose conventions Melville had mastered in earlier works. Several forgotten “Revenge Tragedies” surround Hamlet, just as the Ghost Story underlies Beloved. Many a medieval Vision of Hell preceded the Inferno. The Whodunit flowered into The Name of the Rose.

I used to read passages of Blood Meridian to fortify myself, as if with amphetamines, for the lurid imagery of my first novel, Partitions. I didn’t borrow from Blood Meridian stylistically; the Neverending Sentence doesn’t work when anybody else does it. I tried, instead, to see the way he sees in that book. To infuse with beauty the mindless violence along 1947’s Radcliffe Line between India and Pakistan: To do what McCarthy did for the mindless violence along the Texas–Mexico border in the 1850s. I, too, was seeking to paint a gory, lawless borderland, and McCarthy gave me strength to do it.

Every so often, when I’m feeling tired or uninspired, I go over to Blood Meridian and open it up to any page, the way the old Romans used to do with their Virgil when they wished to know the future. It doesn’t matter what sentence I land on. It pulls me in and drags me for half a page, and I am reminded of what is possible, of how less isn’t always more. Of how more, too, can be more. Just today, paging through it fondly to work myself up for this essay, I came across this passage. What the ex-priest says here of the Judge I’d apply just as readily to Cormac McCarthy.

God the man is a dancer, you’ll not take that away from him. And fiddle. He’s the greatest fiddler I ever heard and that’s an end on it. The greatest.

Amit Majmudar is a diagnostic nuclear radiologist who lives in Westerville, Ohio, with his wife and three children. In addition to the poetry collections and novels mentioned above, he is the author of Godsong: A Verse Translation of the Bhagavad-Gita, with Commentary, and is also the editor of the anthology Resistance, Rebellion, Life: 50 Poems Now. Awarded the Donald Justice Prize and the Pushcart Prize, Majmudar’s work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Best of the Best American Poetry, and the eleventh edition of The Norton Introduction to Literature. He blogs for the Kenyon Review.