“The past is never dead,” William Faulkner famously wrote, “it’s not even past.” This canny observation can serve as an essential key to Faulkner’s work. His characters are haunted by history in ways they can scarcely fathom and his narratives are structured so that events recur again and again, each time told in part and in pieces, a virtuoso literary enactment of the mysterious process by which memory congeals into history. It is also a key to our history as a people, especially with respect to the events that still shape our national life more than any other, the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Literary critic Michael Gorra’s newest book, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, explores the intersection of these two concerns by viewing Faulkner’s novels and stories—the hand-hewn world of Yoknapatawpha County—through the lens of the war and its aftermath, and vice versa. He asks why we should read Faulkner today and what the work still has to teach us about the Civil War and legacy of slavery.

This approach is not without its challenges, for as Gorra notes early on, the war is at once everywhere and nowhere in Faulkner’s fiction, “an all-determining absence, a gap hardwired into the novelist’s very imagination.” But the rewards are great, for it reveals the ways in which this Southern writer achieved a kind of double consciousness that transcended his sectional identity: “it is in his account of the Civil War’s inner meaning and legacy,” Gorra finds, “that he stands above all as a national voice.”

As his new book is released this week, we’re very grateful that Michael Gorra could take some time to visit with us.

Library of America: Your book is remarkably timely, dealing as it does with race and remembrance, and it’s fascinating to read as America grapples once more with the legacies of the Civil War, our perpetually unfinished business. What first inspired you to reread Faulkner for what he has to say, or in many cases for what he cannot say, about the Civil War and its consequences?

Michael Gorra: I spent the academic year of 2010–11 in France, and at that point in my life I was often more acutely aware of American politics when I was out of the country than when I was in it. Looking at it from a distance, but consciously, as opposed to it being simply the air one breathes. And to put things bluntly, what was going on in 2010 was the Tea Party. That’s what I was reading about online, and its rhetoric reminded me of what I knew about the 1860 moment of secession. So I started to look into that earlier moment as a way to understand our own; went from the newspapers to the library, in a sense. One of the books that helped most there, actually, was the first volume of the LOA’s four-volume series, The Civil War Told by Those Who Lived It. I got that as soon as it came out, early in 2011, and then each of the later volumes too, and they became my go–to source for understanding the war as it developed from day to day.

But when I tried to get some perspective on it all, well, I pretty quickly found that Faulkner was a great help. I’d been reading and teaching him for a great many years, he’d always been a point of reference for me, but I’d never written much about him until I realized that by concentrating on him I could bring this newer interest in the Civil War into focus. He became my lens. Of course I couldn’t have predicted the particular relevance that all this has in 2020, the way the burden of the past appears—well, not heavier, precisely, but more on our collective mind, the mind of white America especially, right up in front in a way that it wasn’t even in 2010.

LOA: Before turning to Faulkner’s Civil War you look at the way other writers before him addressed the conflict. It was Edmund Wilson, in his classic 1962 book Patriotic Gore, who first speculated on why the war had not produced any great works of literature, on why fiction did not seem the best way to capture the “switching yard of contingencies,” as you beautifully describe it, of the lived experience of the war. What was it about this period, this civil war, that made it so elusive for its writers? And what was it that led Faulkner to approach the war obliquely, as it were, even some seventy years later?

Gorra: Wilson limited himself to the work produced by members of the war generation, and for a variety of reasons none of the future great novelists who were young men at the time fought—not Henry James, nor Mark Twain, nor William Dean Howells. But that’s a simple answer. A better one would suggest that the war’s meaning wasn’t yet clear, not even to Wilson a century later. You could get a certain limited drama out of the conflict of close friends, of classmates or cousins or even brothers winding up on opposites side, and then out of their postwar reconciliation. But that ignores the real story and struggle of the period, the battle to end slavery, and of course much of the historiography of the post-Reconstruction decades, right on to Wilson’s own time, downplayed the importance of slavery as a motive force. White America simply didn’t want to face that, and so most of the fiction that did get written about the war is evasive. At least on the scale of the novel—there are some superb short stories, and then the narrow, combat-focused brilliance of The Red Badge of Courage.

Even Wilson himself is evasive—Patriotic Gore is a great book almost in spite of itself. Because it omits so much, it says almost nothing about slavery, and he doesn’t even call on Frederick Douglass as a witness. Now Faulkner himself doesn’t ignore it. He sees it as an unhealed wound in both the mind and on the land alike, and yet he also grew up and lived in a South that insisted on the justice of its cause. I think he had to be oblique—or would have had to be, if that hadn’t been his modus operandi already. But then he never approached anything directly.

LOA: Though Faulkner’s fiction is saturated in history, you note that it is not historical fiction in the sense in which we normally think of the genre, if for no other reason than that with Faulkner all the great historical events happen off stage, their determinative force made more formidable for being “not dramatized so much as invoked.” What he seems more interested in might be called memorial fiction, how people come to believe what they believe about the past, how memory operates on them, defines them, in some cases destroys them. How does Faulkner’s sense of how memory works shape the form his fiction takes, both in individual books and in the larger superstructure of Yoknapatawpha?

Gorra: There’s a moment in Absalom, Absalom! in which a character called Rosa Coldfield claims that there’s no such thing as memory, not for her, because memory requires a sense of the past and to her the crucial events of her life are all still present, even though they happened fifty years ago. Fifty years that form a single moment of unending pain. Nothing is past, nothing is over, and though she’s an extreme case a lot of Faulkner’s characters share her general attitude. Hence those famous words: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Quentin Compson in The Sound and the Fury can’t put certain moments in his family history behind him, they burn and sting as if they were happening now, and a part of him wants it to be that way always, he doesn’t want to get over things, because those events, those painful events, are what constitute his identity. They’re who he is. That’s how it works for Faulkner’s characters, and then in the form of the fiction itself you often get one moment falling into another, as if the line between past and present were porous. In reading it’s often hard to know just when you are, and the characters’ present lives are apt to be replaced on the page by a moment from the past that’s even more vivid than what’s going on physically around them.

Faulkner once said that he wanted to put everything between a capital letter and a period—the whole world in a sentence, because so long as it’s a single sentence then everything is happening at once, and past and present are one. Now I’d argue that though this sense of the past, and of memory, may grow out of his own individual psyche, it also has a kind of harmonic resonance with the history of his region, with the way in which white southerners of his generation were always looking back to the Civil War and seeing themselves as living in an aftermath. Their lives determined by something that happened long ago, but that still seems as if present.

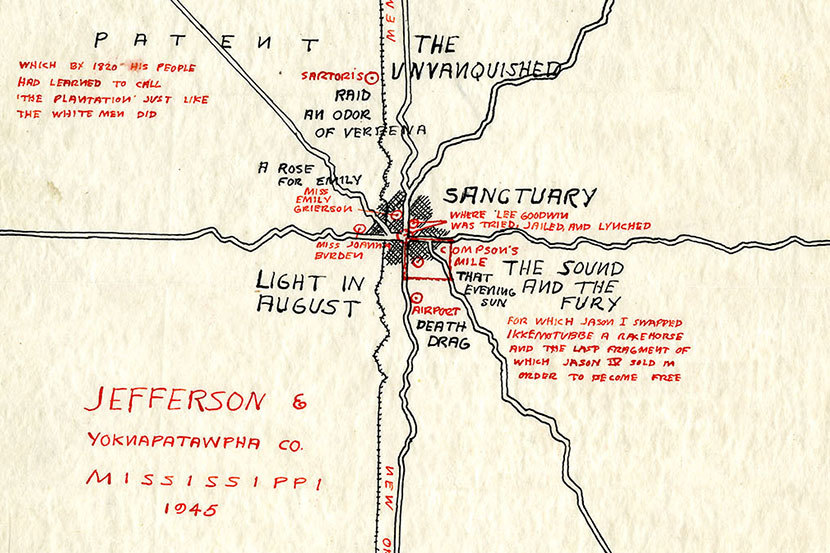

LOA: Speaking of that superstructure, you break it apart here it in order to present a chronology of the war and its aftermath in Yoknapatawpha, something that will serve as an invaluable guide for readers. What did that experience reveal to you about how to approach Faulkner? You suggest, for instance, that readers should not begin with Flags in the Dust (1929), the earliest of the Yoknapatawpha novels, because it “has too many characters and too many plots, and some moments are predicated on books [Faulkner] hadn’t yet written.” Having taught this material for so many years, and now having written this book, is there an order you can recommend for readers who want to tackle Faulkner today?

Gorra: Faulkner’s work presents a set of different but overlapping difficulties. One of them is formal—the endless sentences, the games he plays with time and consciousness. And the other is a question of something like reference: a lot of his books depends on knowing his other books, knowing the characters and plotline that he’s developed in one novel and carried over into another. That’s the case with Flags in the Dust, even though he hadn’t yet written those other books. He had all of Yoknapatawpha County in his mind already, its whole history and people, and he comes close to assuming that his readers already have that knowledge, the stuff that was in his head alone.

| Read As I Lay Dying |

|

| in William Faulkner: Novels 1930–1935 |

So I tell people to start with As I Lay Dying. It’s a technically and formally demanding book, but it’s far from his most difficult, and it’s also one that doesn’t depend on his others. Its main characters, the Bundren family, don’t appear in any his other novels: their story is confined to this one book, and that makes it approachable. After that I’d pick up Light in August—it’s his most complete account of the communal life of Jefferson, the imaginary town at the heart of his imaginary county. And then The Sound and the Fury, his first masterpiece. It doesn’t rely on any of his other novels, but it’s so innovative, it requires such a page-by-page attention, that you do have to train for it, as for climbing a mountain. Maybe a good guide or teacher can get the novice up on top, but to do it yourself, to read or climb it on your own, you’ve got to be in shape, and those other books will get you there.

LOA: The Saddest Words includes a rich discussion of the so-called “local color” literature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, epitomized in the works of such writers as Sarah Orne Jewett, Charles Chesnutt, and Constance Fenimore Woolson. Faulkner’s deep immersion in the language and customs of his Mississippi world (and, frankly, his exceedingly modest sales) would seem to have marked him as a regional writer in this tradition. What was it that enabled him to break loose from that marginalizing trap, to achieve the national and ultimately international stature he attained late in his career and has enjoyed since?

Gorra: Faulkner came of age at a moment when all the rules for writing fiction seemed to have been smashed. Think of Joyce, with his ever-flickering representation of consciousness, and Faulkner was indeed an early reader of Ulysses. But he was also and I think more importantly a close reader of Joseph Conrad, who showed him how to scramble chronology. Experimentation looked possible for a young writer of his generation, possible and necessary, in a way that it hadn’t been for Jewett or Chesnutt or Woolson, all of them writing in a formally less adventurous moment. (Leave aside the fact that Faulkner’s major work is in the novel, rather than in the short story, as theirs was, and as such makes greater claims for itself.) He was a modernist writer as much as he was a regional one, and that’s what first broke him free of that marginalizing trap. But it took foreign readers and foreign critics to make that happen, French ones in particular. Faulkner’s American reviewers compared him to Sherwood Anderson or Thomas Wolfe, or to a series of now forgotten Southern novelists. His French critics mentioned Balzac and Dostoevsky, Homer, Kafka, and Woolf. Those were the right comparisons, the right scale, but as he himself said, “happen is never once,” and a lot of the best recent Faulkner criticism has returned to his Southernness, embedding him within the history that made him. So in reading him it helps to remember both things—Southern and modern, at once and indivisible.

Michael Gorra is the Mary Augusta Jordan Professor of English at Smith College, where he has taught since 1985. He is the author of The Bells in Their Silence: Travels through Germany and Portrait of a Novel: Henry James and the Making of an American Masterpiece, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in the Biography, and the editor of Norton Critical Editions of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury and of the forthcoming Library of America edition of the novels and stories of Elizabeth Spencer.