By Michael Sragow

This fierce interrogation of frontier ethics rises to the level of Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s original novel through the versatile director’s wizardry with actors and cameras.

William Wellman’s superbly acted The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) generates a visceral and emotional force that equals or surpasses the power of Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s ruminative, soul-quaking 1940 novel about a lynch mob out West in 1885. Producer-writer Lamar Trotti’s shrewd, lean adaptation enables Wellman to cleave to Clark’s turbulent events while telling his story with utmost concision and a crystalline attack.

At the start, cowboy partners Gil Carter (Henry Fonda) and Art Croft (Harry Morgan) amble into dreary Bridger’s Wells, Nevada. As semi-strangers, they know they’ll be suspected of being the cattle thieves who’ve been menacing the area. They’re still glad to be in town after the back-to-back ordeals of working winter range and spring roundup. When word spreads that rustlers have shot a local man in the head and stolen his cattle, the outsiders position themselves on the edges of the group readying to snare the culprits and mete out rough justice.

Do Gil and Art sign up for a posse—or a lynch mob? The town’s principled, wily senior statesman, storekeeper Arthur Davies (Harry Davenport, demonstrating why Bette Davis called him “the greatest character actor of all time”), keeps talking the gang down, first from its dumb rage, then from its stubbornness. The movie’s vise-like suspense derives from Davies’ questioning of vigilante justice. The gang’s ramrod and de facto leader, former Dixie martinet Major Tetley (Frank Conroy), seeks a semblance of dignity, if not legality. He knows that the one man who can deputize a posse is the absent sheriff—not the surly deputy Butch Mapes (Dick Rich) eager to do the honors. When they find the supposed bad guys in a mountain pass known as Ox-Bow Valley, Tetley tries to coerce the three suspects into confessing. He also exhorts his sensitive grown son Gerald (William Eythe) to participate in stringing them up, with the humiliating words, “I’ll have no female boys bearing my name.”

Wellman maintains a taut narrative line with just enough give to let us consider life-or-death questions. Why the rush to judgment? The chance for ranchers and townsfolk to prove their manhood by rites of violence? A hard-boiled way to relieve boredom? Doubts do afflict the galloping horde of twenty-seven men and one woman (Jane Darwell as coarse, canny Ma Grier). Would most of the men back away if that didn’t mean looking like cowards instead of tough guys? At times, only the victim’s best friend, Jeff Farnley (Marc Lawrence), and the town drunk, Monty Smith (Paul Hurst), appear committed to a hanging. Wellman generates a staccato momentum as he throws obstacles onto the vengeance-seekers’ path. When Davies and Gil pressure Tetley into giving the trio’s leader a few hours to write a farewell to his wife, they also hope moral sense will return to the “jury” and outweigh the circumstantial evidence. The film’s excruciating suspense rests on its fierce interrogation of frontier ethics. When Gil and Davies, at 3 A.M., successfully argue that the hanging should be put off till daylight, some lynchers respond by treating the delay as a festive barbecue.

Clark filters the other characters’ crudeness and prejudiced or guilt-wracked rationales through Art’s grounded, sane sensibility. The novel catalyzes lump-in-the-throat, twist-in-the-gut tension via the lucid dissection of an atrocity. In the opening section of the book, Art hears someone call the would-be posse “a lynching mob” and thinks to himself, “There was a lot of difference between the way they were going at it and what I thought of as a mob.” Clark raises dread by capturing how quickly time and circumstance can reduce a group of men to a mob or a wolf pack. He maintains our rooting interest throughout by isolating moments when disaster could be averted.

Wellman achieves the same ends with more dynamic means. He demotes Art to Gil’s sidekick. He deletes pages of Davies’ self-flagellation for not stopping Tetley’s gang as well as Gerald’s misanthropic (and misogynistic) jeremiad over mankind’s conformity and cruelty. What Wellman loses in nuance he gains in direct impact. Gil becomes a full-fledged antihero and a magnetic center of attention. Early on he demonstrates that he needs a physical fight now and then to clear his head, but he balances his violence with horse sense and a wary, erratic amiability. He’s in the mob, but not of it, and though he can’t save the day, he has the soul to do his best to make amends.

Wellman illuminates how the armed band’s risky business endangers everyone in or near it. That includes the stagecoach crew and passengers who hurtle down a mountain grade in panic over what they mis-read as a stickup, and Art, who gets wounded by the man riding shotgun.

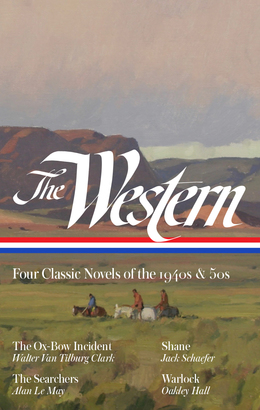

| READ THE NOVEL |

|

| in The Western: Four Classic Novels of the 1940s & 50s |

The terseness of the dialogue (without Art’s narration) and the sharp, intuitive quality of Wellman’s compositions and staging compel us to focus on Fonda’s shifts of expression. It’s one of his greatest dramatic performances, right up there with his title role in John Ford’s 1939 Young Mr. Lincoln (also written by Trotti). He seethes when he discovers that proper matrons ran his woman, Rose Mapen (Mary Beth Hughes), out of town. He glares with squelched desire when she shows up with a dapper husband from San Francisco. But Gil is no creature of the id. He’s got Grade A feelers and Wild West street smarts. He’s intensely aware of the suspicions surrounding himself and Art. He’s attuned to the restless ennui that fuels the “posse,” due process be damned. Shades of meaning as well as gale-like passions emanate from the varying light in his eyes and tension in his face. The legendary Arthur C. Miller did the resourceful, expressive cinematography, achieving a rare balance between realistic and expressionist lighting. He wrings visual art out of studio sets.

Wellman’s actor-based style only seems more conventional than Clark’s exploration of conscience and consciousness. This film supports Ingmar Bergman’s declaration, “The human face is the most important subject of the cinema.” (Bergman also said, “I admire the American directors: Billy Wilder, William Wellman, and George Cukor. They’re an unbeatable trio.”) It’s become de rigueur to say that the motion picture camera reads actors’ thoughts, but in The Ox-Bow Incident Wellman is the rare mainstream director to build an entire film around that concept.

We don’t need a narrator to tell us that Judge Tyler (Matt Briggs) is a self-infatuated humbug: Briggs reveals it with each insecure glance and fustian remark. Wellman’s general insistence on transparent honesty ups the potency of his operatic strokes. As that sloppy alcoholic Smith, Hurst comes on like a burlesque lush, but when he mimes a man caught in a noose, his goofiness turns grotesque. While the doomed men await their destiny at dawn, Smith makes time with Darwell’s prodigiously earthy Ma Grier, whose pernicious cackle drives away any salutary thought. Best of all, Leigh Whipper, the first Black member of Actor’s Equity, cuts a unique, ineradicable figure in an uncredited role. Whipper, who created the crabbed stable-hand Crooks in John Steinbeck’s stage version of Of Mice and Men (1937) and perfected the part in Lewis Milestone’s transcendent movie (1939), conjures an oasis of moral sanity with the tall, thin, wraith-like Sparks, the town’s handyman and unofficial preacher. (Trotti and Wellman wisely remove Clark’s mealy-mouthed white minister.) As Sparks recalls his brother’s lynching, Whipper’s haunted delivery cuts to the bone. After this latest lynching is done, Whipper drops to his knees. As the men scatter and leave him alone in the suddenly silent clearing, Sparks sings with personal urgency to each of the hanged men: “You got to go through Lonesome Valley/ You got to go there by yourself.” The words hover over the men who ride off. There’s no better evidence of the value an alert director like Wellman and an instinctive talent like Whipper can add to an archetypal situation. They elevate the scene to a poetic lamentation.

An astonishingly versatile director, Wellman had already helped define several genres with enduring classics: the wartime aviation movie (Wings, 1927), the gangster film (Public Enemy, 1931), the inside-Hollywood tragedy (A Star is Born, 1937), and the screwball satire (Nothing Sacred, also 1937, and Roxie Hart, 1942). He also made an array of unpretentious or socially conscious melodramas (Night Nurse, 1931, Wild Boys of the Road, 1933) and some unforgettable adaptations (Beau Geste and The Light that Failed, both 1939). Clark’s novel grabbed him as no other material had. It came his way via a struggling producer, Harold Hurley, who touted the novel as a potential Mae West vehicle. According to William Wellman Jr.’s biography of his dad (Wild Bill Wellman: Hollywood Rebel), Hurley told the director, “When the posse and the tired cowboys gather in the saloon, Mae will cheer them up with song and dance.” Eventually, Wellman bought the property from Hurley and sold Darryl F. Zanuck on making it his way at 20th Century Fox.

Wellman was operating at peak inspiration when assembling his Ox-Bow ensemble. As he introduces each new character, every actor contributes a fresh color while working at white heat. The actors playing the accused share instant and affective authority. Anthony Quinn glints with macho pride and sneaky brilliance as the Mexican who claims to speak no English and has gone by at least two names—this time, “Juan Martinez.” Dana Andrews pulls off rapid chain reactions as the anguished Donald Martin, moving in seconds from rational shock to furious innocence to despondency, then teary-eyed defiance. (What a Jean Valjean he could have been!) Francis Ford (John’s older brother) offers a heartbreaking portrait of befuddlement as the nearly senile Alva Hardwicke. John Ford penned a congratulatory note to Wellman (contained in Frank Thompson and John Gallagher’s Nothing Sacred: The Cinema of William Wellman): “It is the best picture I have seen for longer than I can remember”—and concluded with a joke: “The only thing in the picture that didn’t strike me as being real, Billie, was my brother refusing the drink and making such a fuss about getting hung. After all, most of his ancestors have been hung and I just can’t see Frank refusing a drink.”

After managing prodigious feats like indelibly and sparingly etching the Tetleys’ poisonous father-son relationship (only one of them kills himself in the movie), Wellman decides that Fonda’s Gil must read Martin’s farewell letter out loud, though Clark merely—and beautifully—alludes to its contents in his novel. Written by Trotti, this all-too-pious epistle asks, “What is anybody’s conscience except a piece of the conscience of all men that ever lived?” It’s a lot like Fonda’s Tom Joad saying, in Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940), “a fellow ain’t got a soul of his own, just a little piece of a big soul, the one big soul that belongs to everybody.”

This unforced error doesn’t undercut the movie’s staggering accomplishment. Wellman’s wizardry with actors and cameras made even that bad climactic flourish cast a spell on another genius filmmaker. After lining up a dozen lynchers at the bar, each stuck in his own miasma of traumatic guilt, Wellman frames Gil delivering most of the speech with his eyes hidden by Art’s hat. David Weddle, Sam Peckinpah’s biographer, tells of young Sam watching the movie spellbound in San Rafael, California, and describing it to his sister, Fern Lea: “He drank it all in, in the darkness of the theater. Did Fern Lea notice, he asked her after she’d seen it also, how Henry Fonda’s face was hidden by another guy’s hat brim when he read the letter by one of the hanged men? How it kept the scene from getting too mushy and weepy-eyed?”

Weddle writes, “Here was a Western that was more than a Western, that spoke to something deep and inarticulate within Sam.” And not just to Sam Peckinpah, but to dozens of other future writers and directors. With The Ox-Bow Incident, Wellman pioneered yet another genre: the “adult Western.”

Watch: Original trailer for The Ox–Bow Incident (2:13)

The Ox-Bow Incident (1943). Directed by William Wellman. Written by Lamar Trotti, from Walter Van Tilburg Clark’s novel. With Henry Fonda, Dana Andrews, Mary Beth Hughes, Anthony Quinn, and Harry Morgan.

Buy the Blu-Ray • Buy the DVD * Watch on Amazon Video • Watch on Vudu

Michael Sragow wrote Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master (2008) and edited two volumes of James Agee’s prose (2005) for Library of America. He wrote, researched, and coproduced the TCM documentary Image Makers: The Adventures of America’s Pioneer Cinematographers (2019).